Isla Nublar (Bribri: Guá-Si) is a small volcanic island situated roughly 120 miles west of Costa Rica. It was continuously inhabited by the Tun-Si tribe until the 1980s, and was utilized by International Genetic Technologies, Inc. as a tourist destination until December of 2015. The island has been heavily altered by human activity, especially after InGen’s lease of the island from Costa Rica in the early 1980s for the purposes of building Jurassic Park. This first attempt at a theme park failed in 1993, but was resurrected nine years later under the name Jurassic World. This second park was planned during the late 1990s, named in 1999, and constructed between 2002 and 2005; it operated successfully from May 30, 2005 until December 22, 2015, after which point it closed permanently.

As a result of human activity, Isla Nublar was inhabited by many species of de-extinct animals and plants which disrupted its native ecosystem and formed a new ecology of their own. These species were kept loosely under control between 1988 and 1993, lived in the wild between 1993 and 2002, remained firmly in captivity between 2004 and 2015 and returned to the wild between 2015 and 2018. During the summer of 2018, a violent volcanic eruption destroyed most of the island’s ecosystem.

As of 2016, the island was under United Nations quarantine, but local Costa Rican authorities withdrew support in early 2018, leaving the island mostly unprotected.

Name

The island’s original name is Guá-Si, meaning “house beyond water” or, more simply, “water house” in the Tun-Si dialect of the Bribri language. Its Spanish name, Isla Nublar, was coined in 1525 by Nicolas de Huelva, cartographer for the carrack La Estrella. The name Isla Nublar translates roughly to “cloud island.” It is heavily speculated that the name is a reference to the island’s volcanic mountain, which was active and producing smog in 1525 when La Estrella sighted it. However, the name may also be a reference to the cloud forest environment which is commonly found across the island.

The Spanish name has become almost universally recognized and used by people from around the world. Names for the island in other languages are almost never heard, even though the island has been owned by American and Indian companies and was heavily staffed by English-speaking personnel between 1988 and 1993 as well as 2002 to 2015.

Location

Isla Nublar is located in the Gulf of Fernandez within the East Pacific Ocean, situated roughly 120 miles (193 kilometers) away from the nearest Western Costa Rican mainland. It is located at °48’11.4″N, 88°36’42.9″W. It is located on the Cocos Plate, just west of the Middle America Trench and the border with the Caribbean Plate.

Description

This island is about 22 square miles (56.98 square kilometers) in area, considerably wider in the north and narrowing in shape toward the south. From north to south it is roughly eight miles long, and at its widest point from east to west it is three miles wide. Its southern region gradually expanded between 1525 and 1993 and became narrower again between 1993 and 2015, but the island has overall retained a shape often likened to an inverted teardrop. Most of the island consists of igneous rock deposits created by the stratovolcano located in the island’s northwest, called Mount Sibo.

Isla Nublar is geologically young, as are most islands in the area, and is likely only a couple million years old. As a result, many of its mountains and cliffs have yet to erode, and steep rises dominate much of its geography. Its mountains are generally less than two thousand feet high, however, and Mount Sibo is its geographically highest point (it was measured at 2,058 feet or 627.28 meters in 1993). Depending on the classification used, Isla Nublar can be said to have either two or three mountain ranges. The eastern and western mountain ranges are simply called the Eastern Ridge and Western Ridge. The mountains in the north are often considered part of the Western Ridge, but are sometimes considered a separate range. They are called the Chavarria Mountains in the Ludia mobile game series, though a t-shirt sold by Universal Studios labels the area including Mount Sibo as the Ismaloya Mountains. The separation of these two ranges is more prominent in the twenty-first century, as erosion has created a gap between the northern and western mountains. Both the Eastern and Western Ridges run north-to-south, but the Western Ridge spans a broader area; in 1993, it extended completely from the northern to the southern points of the island. As of 2015, a section in the northwest had eroded to create flatland that divides the mountains. The Eastern Ridge is considerably smaller than the Western, spanning only a few miles in the middle part of the eastern side of the island.

The Eastern Ridge borders an area on the coast called the Sudden Drop, an area of high cliffs which lead to the ocean. Similarly high cliffs exist across many parts of the northern and eastern coasts, but much of Isla Nublar’s coastline is more accessible and even includes many small sandy beaches. Surrounded on all sides by the Pacific Ocean, the island’s coasts are constantly subject to wave action. As a result, the age of certain beaches can be determined based on their substrate; the oldest beaches are sandy, while younger beaches are rocky and the youngest still have exposed bedrock and intact cliffs.

In between the mountain ranges that frame the island is a large central valley which contained abundant plant life prior to volcanic activity in 2018. The valley contained forest, shrub, and grassland environments, though human activity reshaped parts of the valley to accommodate tourist attractions between 1988 and 2015. Plant life was densest around the Jungle River, which supported a tropical rainforest environment due to the heavy rainfall the island often experienced. Since 2002, a large section of the central valley has been built over with a tourist facility centered on the massive Jurassic World Lagoon, while the northern part of the valley has expanded noticeably. Other areas of flatland exist to the east of parts of the Eastern Ridge, and as of 2015, a region in the west had eroded into flatland referred to as the West Plains.

The Jungle River has always been one of the most important sources of fresh water on Isla Nublar. Fed by rainwater and runoff from the mountain ranges, it is the most significant river on the island and the only one known to have a formal name. Maps from 1525 indicate that the Jungle River once connected to the northern lagoon, but today these bodies of water are unrelated. Maps from this era also indicate that the river reached all the way through the Western Ridge to the coast, and that there were two branches of the estuary (the northern of which had two sub-branches). As of 1993, the main tributaries of the river came from the northern and western mountains, converging in the southern part of the central valley before moving eastward into an estuary. Large-scale landscaping throughout the twenty-first century cut off the western tributary, and a moderately-sized lake formed in the northern part of the valley near the mountains. The northern tributary has since changed in shape, becoming more meandering and forming another lake in the south. The estuary has once again split into two, analogous to the old riverbed (though not in the same location).

In the north, a large tidal river fed by runoff from the northern mountains provides fresh water to that area of the island. It has few to no major branches, but was wider than the Jungle River in 1993 due to the island’s geography in that area. The northern river has reduced with time, likely due to erosion from the mountains filling it up. Maps circa 1525 suggest that it was once connected to the Jungle River to the north of the Eastern Ridge, effectively cutting Isla Nublar in two. The northern lagoon is a part of the younger coast of the island, and so is defined by a sudden, steep drop-off and underwater cliffs riddled with both extinct and active lava tubes.

Other sources of fresh water on the island are constantly changing, influenced by human intervention as well as natural events such as weather and seismic activity. As of 2004, five waterfalls were known on the island; the locations of smaller rivers, lakes, and ponds have changed over time as some bodies of water run dry while new ones form. These, in turn, influenced the variety and density of plant life found across the island. Some marshland exists in the southern part of the island, but little of it has been observed directly; nearly all of the island’s fresh water exists in rivers, lakes, and ponds.

Isla Nublar is considered to have a tropical monsoon climate, based on the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system. This means it has warm temperatures year-round and experiences wet and dry seasons; located just north of the equator, Isla Nublar does experience seasons but not to the extreme that people in northern climates would be familiar with. During the rainy season, which occurs from May to mid-November, Isla Nublar often experiences tropical storms. The dry season occurs from mid-November through April, and sees considerably less rainfall. Its yearly average temperature is 75 degrees Fahrenheit (23.89 degrees Celsius).

While Isla Nublar historically was covered in dense cloud forests including a diverse array of plant life, much of its forest cover was lost after a volcanic eruption on June 23, 2018. Volcanic activity has altered many aspects of island climate, causing ashfall and smog over the northern regions and causing water sources to become polluted. The loss of forests has also likely changed the environment on the island, as transpiration from plants would have been a major source of water vapor and thus the moisture that the island came to depend on. Without the dense cloud forest and lowland jungle, Isla Nublar has probably become hotter and drier since the 2018 eruption. However, as of 2022, the eruption had subsided considerably and there are signs of recovering plant life.

Offshore of Isla Nublar are a number of smaller islets, the names of which are currently unknown. The islets appear to be temporary, and so some may not have names. In 1993, a southward-curving sandbar formed by deposition from the Jungle River supported a chain of islets proceeding toward the south, but these appear to have disappeared by 2015. By that time, newer islets had appeared in the surrounding waters. Changing currents, new river formation, and other hydrogeological changes are believed to create and destroy these islets over time.

History

Origin

Isla Nublar formed from a volcanic seamount on the Cocos Plate west of the Middle America Trench, a major subduction zone. The exact period of time at which it formed is unknown, but it is believed to be around the same age as Cocos Island, which is roughly two million years old. As volcanic activity continued, the island eventually emerged from the ocean and continued to expand. The southern parts of the island are most likely formed from lava flows during the island’s period of greatest activity; Mount Sibo is the largest mountain and only surviving volcano on the island and so is generally believed to have been present when the island first formed. Geological evidence suggests that the island formed north-to-south, but that the spread of lava reduced over time. This means that the southern part of the island consists of the oldest lava rock, while the northern part of the island contains progressively smaller areas of newer lava rock. There were probably other volcanoes, now fully extinct, that once existed elsewhere on the island during its formation.

As the island expanded, plant life took root on its surface. These would have at first been hardy pioneer species, mostly from the Costa Rican mainland. After the environment had become ameliorated by these species, other plants could take root. The first animals on the island were most likely seafaring creatures such as the birds which can still be seen there today. Marine mammals such as seals or sea lions may also have come to the island during its early years. Over time, more terrestrial creatures began to make homes there, and an ecosystem formed.

At some point, the tufted deer Elaphodus cephalophus arrived on the island from Asia, thousands of miles away across the ocean. How it arrived is unknown, though the fringe theory that the ancient Chinese discovered the Americas thousands of years ago has been brought up. In any case, the tufted deer of Isla Nublar eventually evolved into a distinct subspecies, E. c. nublarus, and became the island’s most common endemic creature.

Prior to 1525

As early as the first millennium BCE, the island was inhabited by humans. Among the island’s first human inhabitants were the Tun-Si, a tribe of the Bribri people, themselves autochthonic inhabitants of Costa Rica. According to Jurassic Park: Builder, the first of the Ludia series of mobile games, the Boruca people also came to live there. The island’s inhabitants lived off of the abundant natural resources, particularly the fish found in the surrounding waters. The land was named Guá-Si, meaning “Water House” or “House Beyond Water” in the Tun-Si dialect.

The Tun-Si tribe is known to have farmed goats on Guá-Si, introducing a species not naturally found there. Goat-herding paths were carved into the hillsides and cliffs, allowing the people to move their livestock from place to place. Mount Sibo was considered sacred to the Tun-Si due to its resemblance to a Bribri conical house, which holds extreme spiritual significance. The mountain was believed to have been built by the animals of the world, a belief which tied into the respect that the Tun-Si had for their land. Apart from the introduction of goats, the island’s human inhabitants did little to seriously alter the ecosystem and relied on nature for their survival. During this time, volcanic activity was relatively limited, not posing a serious threat to the people of Guá-Si.

1525: European discovery

Europeans explored the Americas during the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Spanish claiming much of Central America as their own. In 1525, the Spanish carrack La Estrella traveled along the Pacific coast of Costa Rica under the guidance of its captain Diego Fernandez (probably the conquistador Diego Fernández de Proaño). The ship’s cartographer, Nicolas de Huelva, took note of a plume of volcanic smog rising from a position out in the ocean. This smog was the result of a recent eruption of Mount Sibo. While this eruption did not cause irreparable harm to Guá-Si’s inhabitants, it did lead the Spaniards directly to the island. It was given the name Isla Nublar by de Huelva, likely in reference to the clouds of volcanic smog that led to its discovery.

Europeans explored the Americas during the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Spanish claiming much of Central America as their own. In 1525, the Spanish carrack La Estrella traveled along the Pacific coast of Costa Rica under the guidance of its captain Diego Fernandez (probably the conquistador Diego Fernández de Proaño). The ship’s cartographer, Nicolas de Huelva, took note of a plume of volcanic smog rising from a position out in the ocean. This smog was the result of a recent eruption of Mount Sibo. While this eruption did not cause irreparable harm to Guá-Si’s inhabitants, it did lead the Spaniards directly to the island. It was given the name Isla Nublar by de Huelva, likely in reference to the clouds of volcanic smog that led to its discovery.

Fernandez explored the area around the island extensively, making contact with the indigenous people. His interactions with them are largely unrecorded, but he at least learned the name of the Tun-Si tribe, that they were a member of the Bribri people, and that the island was called Guá-Si. Though he learned the island’s proper name, he continued to call it Nublar, and the Spanish moniker became standard.

Inclement weather around the island during the rainy season was often hazardous to passing ships. At least one major shipwreck occurred near Isla Nublar in the 1520s, located off the island’s western coast, when a Spanish vessel was sunk during a storm.

1525-1985: European colonialism

From 1525 onward, more Europeans passed near the island, charting its shores and the features on the island itself. At least one large ship is believed to have sunk off the western coast due to a squall; its name was not recorded on the map that this wreck is known from. Some Spanish came to settle on the island, with some modern-day Tun-Si people still having Spanish surnames. Events occurring in the years that followed resulted in many of the island’s inhabitants being forced to relocate to the mainland.

Despite the difficulties they faced following European discovery, the Tun-Si tribe was able to maintain some semblance of normal life for hundreds of years. They continued to fish in the sea and herd goats as their ancestors did, and continued the spiritual traditions they had always practiced. Mount Sibo remained dormant for all this time, reducing the natural hazards the island’s people had to face.

The country of Costa Rica became recognized in its modern form with the publication of its Constitution on November 7, 1949; sometime after this, it acquired Isla Nublar as territory along with the more isolated Muertes Archipelago farther west. This does not seem to have impacted Isla Nublar much, as the island continued to operate as it always had.

The fate of Isla Nublar, however, would be up in the air beginning in the early 1980s. International Genetic Technologies, an American genetics company founded by Scottish entrepreneur Dr. John P. A. Hammond, had sought an isolated property to perform clandestine de-extinction research and turned its sights on Costa Rica’s Pacific islands. Isla Sorna and the neighboring islands of the Muertes Archipelago were leased for 99 years from Costa Rica in 1982. Around the same time, one of the Tun-Si’s prominent awas and patriarch of the Cruz family relocated to the Costa Rican mainland with his daughter Nima and granddaughter Atlanta; their reasons are currently undisclosed, but are assumed to be related to InGen’s interest in buying Costa Rican islands.

InGen would not explicitly show interest in Isla Nublar until 1985. Before then, it had planned to build its de-extinction theme park in San Diego, California where it already owned property. These plans were altered by Hammond in 1985 with his decision to build Jurassic Park on Isla Nublar instead, favoring the mystique of an isolated tropical environment. The Costa Rican government was more reluctant to let Isla Nublar go than they had Isla Sorna; they brought Cruz in to help them sell the island for a higher price, but also insisted that he cut his hair and wear a suit in order to appear more in line with Western ideals of civilization. Cruz complied, and his testimony of Isla Nublar’s natural beauty ensured that InGen agreed to Costa Rica’s higher prices.

Isla Nublar was added onto the 99-year lease that InGen had taken out in 1982, meaning that they would now own the island until 2081.

1985-1987: Relocation and resettlement

Since Jurassic Park was not to be a public project, InGen could not have Isla Nublar still inhabited while construction took place. The relocation of the native people was planned almost immediately and began before the year was out. Mercenaries, including Oscar Morales, were hired to assist in relocating the people of Isla Nublar to the Costa Rican mainland.

InGen and Costa Rica promised that, upon reaching the mainland, the Tun-Si people would be provided with schools, housing, and medical care as compensation for having their land taken. According to Nima Cruz, who witnessed the relocation arriving to the mainland, InGen and the government failed to uphold their promises. The schools were never staffed, the housing was located in slums, and the medicine was largely contaminated if it was delivered at all. The displaced Tun-Si had to adapt to unfamiliar jobs and lifestyles, and many of the young women are believed to have fallen into human trafficking.

By the end of 1987, all of the indigenous people of Isla Nublar had been removed by InGen and the mercenaries they had hired.

1988-1993: Jurassic Park

Construction of InGen’s Jurassic Park commenced in 1988, the year after the last Tun-Si were relocated off the island. Within months, a system of electric fences and other security measures were put in place, powered by a geothermal power plant installed within Mount Sibo. A sprawling network of maintenance and service tunnels came under construction beneath the island. Animal care staff were hired by the year’s end, and the first de-extinct life forms were introduced from Isla Sorna. These included Triceratops and Brachiosaurus, and possibly others such as Parasaurolophus. The first theropod, a one-year-old Tyrannosaurus, was introduced in 1989. De-extinct plant life, including at least one Cretaceous species of veriforman, were also cloned and introduced.

Tourist attractions came under construction along with the animal paddocks. The Park’s centerpiece was to be the Visitors’ Centre, a huge facility devoted to education and entertainment. As of 1993, it was still under construction but featured a fully-functional control room and laboratory. The control room allowed staff to monitor the entire island and use its technologies remotely. By 1991 or 1992, an automated tour program had been created and electric Ford Explorers were purchased for it.

In late 1991, InGen’s lead geneticist Dr. Henry Wu succeeded in completing the genomes of two new theropods, Dilophosaurus and Velociraptor, though they exhibited exceptionally large numbers of phenotypic errors. These new animals were introduced to Isla Nublar probably in 1992 or 1993. At some point, Gallimimus was also introduced, likely around the same time, and four Herrerasaurus were brought to the island in early June of 1993. By this time, Tylosaurus and Troodon had been bred but not officially added to InGen’s species list, and Pteranodon may have been introduced under similar circumstances. Compsognathus was among the other animals intended for the Park, but its paddock was not yet ready by 1993; however, the animal was accidentally introduced to the island without InGen’s knowledge.

The development of Jurassic Park was not without a great amount of difficulty. The secrecy was a challenge in and of itself; InGen employed dozens of people who would have explicitly known about the Park and de-extinction. Leaks were mostly dismissed as conspiracy theories, but some were taken seriously by InGen’s rival companies such as BioSyn. Financial difficulties also plagued the Park, particularly after the project’s main beneficiary Benjamin Lockwood quit due to moral disagreements with Hammond. The biological aspects of the Park also created many problems. Though InGen hired paleontological consultants and expert veterinarians to determine how to best care for the animals, the reality of de-extinction was that there were many features of the artificial ecosystem that they could not predict and therefore could not adequately deal with.

Much of dinosaur biology was still undiscovered and simply could not be determined from fossils. A prime example would be the behavioral traits of the highly intelligent Velociraptor; InGen had not anticipated their social behaviors, which led to conflict bewteen the animals and InGen personnel. In 1993, a new Velociraptor took over the pride and initiated violent conflict with the other animals, resulting in the deaths of all but three. The animals systematically tested the fences for weaknesses during feeding time, which prompted their relocation to a holding pen and a serious reconsideration as to the raptors’ role in Jurassic Park. During relocation, the animals attempted to breach containment and mauled a worker to death, which halted most of the construction on the Park.

InGen’s Board of Directors demanded that the Park undergo a safety inspection and endorsement by outside experts. Legal consultant Donald Gennaro was brought on board for this purpose, as were prominent American scientists Dr. Alan Grant and Dr. Ian Malcolm. The scientists were contacted during the first weeks of June; while Grant was being interviewed by Hammond, an invitation was also extended to his partner Dr. Ellie Sattler. Hammond’s grandchildren, Lex and Tim Murphy, were invited to the island to partake in the endorsement tour as well. The tour members arrived on June 11, as did veterinarian Dr. Gerry Harding‘s daughter Jess for unrelated reasons.

During the tour, the majority of InGen’s staff returned to the mainland for the weekend, leaving a skeleton crew consisting of chief engineer Ray Arnold, chief programmer Dennis Nedry, park warden Robert Muldoon, paleogeneticist Dr. Laura Sorkin, Sorkin’s assistant David Banks, and Hammond. While Dr. Harding was intended to leave the island with the rest of the staff, he failed to reach the boat in time due to discovering an injured Nima Cruz on a service road.

Cruz, along with Nedry and a BioSyn employee named Miles Chadwick, had been hired by BioSyn’s Lewis Dodgson to steal trade secrets from InGen that night. Nedry, dissatisfied with his salary, had agreed to acquire frozen dinosaur embryos by sabotaging Jurassic Park’s security programming to shut the security systems down. While he was supposed to deliver the goods to Cruz and Chadwick at the East Dock before the boat left, inclement weather caused him to crash his vehicle en route and he was subsequently killed by an escaped dinosaur. While attempting to recover Nedry’s package, Chadwick was also killed, and Cruz was wounded by another escaped animal.

As Nedry did not survive his own sabotage efforts, the Park’s security systems could not be restored by the remaining staff. The phones were shut down in the sabotage as well, leaving those who remained unable to call the mainland for assistance. The endorsement tour members, except for Dr. Sattler, became stranded among the animal paddocks; Gennaro died due to an animal attack and Dr. Malcolm was wounded, but rescued by Muldoon and Sattler shortly thereafter. The Murphy children and Dr. Grant were forced to make a day-long trek across the island to reunite with the others. Attempts to restart the Park’s power were successful on June 12, but Muldoon and Arnold both died in the process. Nonetheless, the survivors (Hammond, his grandchildren, and Drs. Grant, Sattler, and Malcolm) were rescued that day. Cruz and the Hardings, as well as Dr. Sorkin, remained on the island until June 13; Banks had died on the 11th or 12th due to escaped animals. InGen sent two teams of mercenaries to rescue the remaining survivors, but this effort was a failure; all but two members of the teams died shortly after arrival on June 12, and the remaining two died before the operation was completed. The Hardings escaped by boat in the morning of June 13, though Dr. Sorkin died while attempting to protect the de-extinct animals. Cruz may have died on June 13, though accounts of her fate are inconsistent.

InGen requested that the U.S. Air Force bomb Isla Nublar with napalm on June 13, with orders to go ahead confirmed the night before. The last of the surviving mercenaries, Billy Yoder, apparently confirmed the deaths of all survivors aside from himself; however, as the Hardings later turned up alive, it instead appears that Yoder had gone rogue in an act of despair after losing his companions. For unknown reasons, the napalm bombing was halted before any damage could be done to Isla Nublar.

Though Isla Nublar’s security systems were restarted before the incident was over, the structural damage done to the island in the intervening hours ensured that the escaped animals could roam the island without hindrance.

1993-2002: An artificial ecosystem

After Jurassic Park was abandoned in June 1993, the surviving de-extinct animals were free to establish themselves anywhere on the island. The tyrannosaur claimed the entire island as territory, with no other large predators able to challenge it. The Dilophosaurus remained as a united social group, though one of their members had died during the incident, and lived nomadically in the forests of the island. The Brachiosaurus herd stayed near their original paddock areas, one of their members dying of malnutrition sometime within the year after the incident. The Triceratops population suffered greatly, with only two animals left alive by late 1994, and the Gallimimus and Parasaurolophus were heavily preyed upon by the tyrannosaur. It is unknown how many Velociraptors survived by 1994, and records are absent for the Tylosaurus, Troodon, and Pteranodon. While they were introduced unintentionally, Compsognathus flourished on the island. The remaining livestock, mainly goats, escaped into the wild and became invasive as well.

In 1994, InGen returned to the island for several months to catalogue specimen numbers and assess the state of the island. Beginning in May and continuing through at least November, the island was investigated; the cleanup operation had several main objectives: to determine how many animals were still alive, how the lysine contingency had been avoided, whether any viable embryos remained, and what had caused the incident. In November, chief geneticist Dr. Henry Wu was also brought to the island to determine how the dinosaurs had begun breeding, which he found to be a side effect of his genetic engineering techniques. The findings of the operation were published in a confidential report in October of 1994.

Geomagnetic disturbances made navigation around Isla Nublar difficult, and also presented a challenge to mapping as compass readings were unreliable in that area. Since Isla Nublar was of no importance to the public, it was simply left off many maps. This worked in favor of both InGen and the de-extinct life on Isla Nublar, as members of the public had no interest in investigating this remote and supposedly insignificant island.

The animals and plants introduced by InGen on Isla Nublar established themselves alongside the native life, forming a unique ecosystem unlike anything in the natural world. No human interference is known to have occurred on the island between 1995 and 2002. In 1995, Dr. Ian Malcolm went public about his experiences at Jurassic Park in a television interview, but was widely dismissed as a fraud due to the efforts of InGen’s Peter Ludlow; Hammond was deposed as CEO in early 1997, after which the general public learned about Isla Sorna and the truth of de-extinction. Isla Nublar, however, remained mostly unknown.

2002-2005: Construction of Jurassic World

In 1998, InGen was bought by Masrani Global Corporation, an Indian megacorporation with interest in many scientific fields including bioengineering. Plans to revive Jurassic Park began almost immediately, with illegal research and development occurring on Isla Sorna between late 1998 and early 1999. A name for the revived Park, “Jurassic World,” was decided upon in October 1999 by Masrani Global’s CEO Simon Masrani. At the time, de-extinct life was protected by the U.S. government under the Gene Guard Act, which also prohibited further de-extinction research. The United Nations did allow Masrani Global limited access to Isla Nublar and Isla Sorna, though access to the general public was prohibited.

2002 saw the return of human activity to Isla Nublar on the large scale. In April, InGen landed on the island to begin recapturing animals to prepare for Jurassic World. The tyrannosaur in particular was captured during Week 3 of the operation, on April 19, under the supervision of InGen’s new head of Security Vic Hoskins. Most of the animals were shipped to Isla Sorna temporarily while construction took place; the tyrannosaur remained on Isla Nublar, as did the Dilophosaurus and Compsognathus.

Masrani Global brought in all its available assets for construction, including Axis Boulder Engineering and Timack Construction (the latter of which was founded in 2002 explicitly for the purpose of building Jurassic World). All together, Masrani Global spent US $1,200,000,000 on construction materials. Containment for the remaining animals was achieved through the constrution of new paddocks and a large security wall, which cordoned off the entire northern part of the island.

In March 2003, the Gene Guard Act was watered down by the U.S. House Committee on Science after bribery by members of Masrani Global Corporation. This was justified by claims that reducing regulations would allow Masrani Global and other corporations to further use genetics to research medicine and health, which would benefit human life as well as the de-extinct animals that the Gene Guard Act was originally created to protect. Reducing the restrictions allowed InGen to resume research, working on species that they had already created and attempting to clone new species from ancient DNA. Jurassic World’s 2005 opening date was publicly revealed that year, though the previous year a 2004 opening date had initially been given. The world became enthralled with Isla Nublar; fans attempted to get an early look at the park, and drone footage of the main entrance gates leaked online by the end of the year.

Much of the original Jurassic Park infrastructure was deconstructed to make room for Jurassic World, including most of the old paddock areas (sections of the tyrannosaur paddock remained intact in regions that were not used for Jurassic World). Other structures were repurposed, including the maintenance tunnel network and radio bunkers. The North Dock was also reused, but was renamed the East Dock as the original East Dock was no longer in use. Simon Masrani had considered using the Visitors’ Centre as an attraction, but the decision was ultimately made to abandon association with the old Park entirely. The Visitors’ Centre was abandoned in a small restricted area, but was not deconstructed. The island was also prepared for animals to return, with new security systems put in place. Water sources were treated with a calcium-boosting supplement, which was intended to ensure bone and tooth health in the dinosaurs. However, this substance formed a mutagenic compound with igneous rock found on the island, causing a mutation in native cyanobacteria which led to the microorganisms becoming highly acidic.

In 2004, animals were returned to Isla Nublar from Isla Sorna. Two adult Brachiosaurus from the original Park named Agnes and Olive were the first animals to be brought back in early January; interns arriving on January 15 took part in overseeing their health and wellbeing. InGen began testing an innovative new vehicle, the gyrosphere, which was intended to be used by guests to view the dinosaurs in the valley up close. On February 2, Olive was found to have a potential tumor in her neck; it was surgically removed the following day, though it was discovered to only be an abscess. The cause was unknown, but suspected to be environmental. The actual cause was the acidic cyanobacteria found in a watering hole in the valley, though this would not be discovered until later.

Agnes was also found to have an abscess in her neck on February 3, but this was remedied with the use of antibiotics and surgery was not deemed necessary. Over the course of the next month, intern Isobel James was tasked with ensuring that the recovering brachiosaurs remained in good health; she also took upon herself to investigate the cause of the abscesses, though this was not a part of her job and was discouraged by InGen Security. She had discovered the acidic cyanobacteria on March 1 by sneaking into the valley while Security’s Asset Containment Unit division was busy test-driving gyrospheres; she did not relay this information to her superiors as she was suspicious that she herself was being investigated by some unknown party. On March 5, a severe storm struck the island, forcing its complete evacuation. James remained behind to manually free Olive from her quarantine paddock due to a fire which broke out during the storm, but died in a vehicular crash on the way to the dock. Her death was ruled an accident despite some evidence of foul play, and her family was paid to keep quiet. In public record, her death was said to have occurred in her home in Boston and her involvement on Isla Nublar was kept secret. The other interns were dismissed and their program was kept classified. Simon Masrani began the process of hand-picking new interns to replace them.

In the spring, two new female brachiosaurs were introduced to the valley. These included a six-year-old named Pearl and a slightly older adolescent named Dot. They were not direct descendants of Agnes and Olive, and therefore the adults did not exhibit parental behavior toward them. Pearl was of particular difficulty for ACU due to her tendency to use gyrospheres as toys, though she did not play with the vehicles while they had passengers inside. Female Triceratops were also introduced to the valley, fifteen in total. They were found to have abscesses similar to those found in Agnes and Olive; these were treated with antibiotics, and from that point onward all of the new animals were put on regimens of antibiotics and steroids to prevent further afflictions. This included eggs; the eggs of several species were incubating in the new Hammond Creation Laboratory by this point, and six Ankylosaurus were hatched in the lab. They were not introduced to the valley due to concerns about conflict with the Triceratops, but Parasaurolophus and Gallimimus were successfully reintroduced.

Most of the new park infrastructure was put in place by 2004, including most of the guest facilities centered around the three-million-gallon Jurassic World Lagoon. This artificial body of saltwater was intended to house ancient marine species, including a Mosasaurus which Dr. Wu was working on. Instead of reusing the Visitors’ Centre, Masrani Global built a new attraction called the Innovation Center; it was sponsored by Samsung. A new aviary was under construction, and the eggs of a newly engineered variety of Pteranodon were incubating in the laboratory by the summer.

The new interns were all selected by August and were brought to Isla Nublar that month. By that point in time, much of the park was functional, and Masrani Global was preparing to ship the remaining animals from Isla Sorna. By that point, the other island was facing an overpopulation crisis due to the illegal cloning which took place in 1998 and 1999; however, official explanations blamed disease, poaching, and territorial behavior for the crisis.

Like the winter internship program, the Bright Minds program that took place during the summer ended in disaster. While the program did have its successes, including developing an improved stimulation regimen for Pearl that allowed her to remain in the valley safely, corporate espionage occurred behind the scenes. Two of the interns, Tanya and Eric Skye, had been bribed by Masrani Global’s rival Mosby Health to steal trade secrets from Jurassic World. These included fusion bandages, high-strength tranquilizers, and data on Velociraptor antirrhopus. In exchange, Mosby Health would provide the siblings’ younger sister Victory with free medical treatment for her potentially fatal heart condition. While attempting to retrieve data on a female raptor, which was delivered to the island in September and slated for a confidential project, the twins accidentally freed the animal. It had been shipped to Isla Nublar alone to prevent it organizing with fellow raptors during transport, but was nonetheless dangerous and aggravated due to its sudden change in environment. The animal was successfully recontained in the quarantine paddock by one of the interns, a political science student named Claire Dearing, but this incident still caused the death of their fellow intern Justin Hendricks.

Bright Minds was ended following Hendricks’s death. Like the incident involving Isobel James, his death was covered up to prevent delays to Jurassic World’s construction. The raptor involved with the death was euthanized. Dearing, who had been roomed in Isobel James’s former quarters, had discovered James’s journal and learned of the acidic cyanobacteria and the suspicions that James had regarding her superiors. Dearing confronted Simon Masrani regarding James’s death and learned what Masrani purported to be the truth. She also gave Henry Wu the information necessary to discover why the dinosaurs in the valley had been developing abscesses. Masrani, impressed by Dearing’s resourcefulness throughout the program, offered her the opportunity to stay on Isla Nublar rather than return to college in Wisconsin and a position at Jurassic World when the park opened the following year. She accepted his offer.

The remaining animals from Isla Sorna were all purportedly shipped to Isla Nublar between 2004 and the time the park opened in 2005, though there is some evidence that InGen activity continues on Isla Sorna. By 2005, eight species were present in the park proper, while the remainder were kept in habitats in the north of the island. The park opened its gates on May 30, and 98,120 visitors came to the island throughout June.

2005-2015: Jurassic World operates

Jurassic World was immensely popular from the day it opened, having been subject to a media frenzy since 2002. Construction on the island was met with controversy from environmentalist groups, but Simon Masrani had already agreed with the Costa Rican Environmental Protection Society to ensure the safety of Isla Nublar’s natural wildlife. He also attempted to make reparations to the Tun-Si people, providing them a reservation on Isla Nublar where they could resume their traditional way of life while having their history honored by the corporation.

The facilities at Jurassic World were far more extensive than those of Jurassic Park, and therefore did disrupt some of the native ecosystem. Attractions such as the Golf Course and Bamboo Forest would have replaced naturally-occurring forest areas, and Mount Sibo was still utilized for geothermal power. In other parts of the island, though, the native forest remained largely undisturbed, and the seabird colonies of the coastlines were left mostly untouched.

By 2007, new species were being hatched on Isla Nublar. The Mosasaurus genome was finally perfected in 2006 or early 2007, and by May of 2007 the reptile had been bred and introduced to the Lagoon. Claire Dearing, meanwhile, had risen to the position of Senior Assets Manager at the park, in charge of managing all the company assets. This gave her nearly as much authority as Vic Hoskins, who had worked there since 2001, and she was generally treated as second in command to Simon Masrani himself.

In 2008, a new age at Jurassic World began. On April 4, Masrani Global’s Board of Directors unanimously decided in a meeting with Simon Masrani that Jurassic World needed a new attraction to boost attendance rates and keep investors interested. After all, every time new attractions were revealed, attendance spiked at the park, and operating costs were continuing to climb faster than revenue could keep up. Simon Masrani and Claire Dearing authorized Henry Wu to use genetic engineering to create a new attraction unlike any they had seen before. Using concepts he had researched throughout his career, Dr. Wu used the Tyrannosaurus rex genome as a template for a novel genus of animal. Likely around 2009 (with deleted canon points suggesting April 9), Dr. Wu succeeded with Experiment E750, hatching an organism called Scorpios rex. Unfortunately, it was unpredictable, dangerous, and not visually appealing; after an incident in which it attacked Dr. Wu to near-fatal effect, Simon Masrani had it slated for destruction. Wu did not follow orders, keeping the animal in cryonic stasis instead. Research took place over the next three years, culminating with a new and more refined version, the Indominus rex. Two Indominus hatching in 2012.

Early that same year, Dr. Wu also engineered a new breed of Velociraptor as specimens of the existing subspecies proved too unpredictable to be compatible with human interaction. The Integrated Behavioral Raptor Intelligence Study took place beginning in 2012, overseen by Hoskins. Wu’s new raptors were hatched prior to May 15 and were imprinted on InGen animal behaviorist Owen Grady, who had previously worked in the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program. Grady studied the raptors’ social behavior to try and determine how best to integrate them into Jurassic World. Claire Dearing was eventually given the position of Operations Manager, treated as second-in-command to Simon Masrani himself. She was close to Hoskins in rank, though belonging to a different division at InGen.

Both the Indominus and I.B.R.I.S. projects were also of interest to Hoskins, who correctly predicted that Jurassic World’s perpetually-rising operating costs would be its undoing and that InGen would need to branch out further. As head of Security, he believed that the answer lay in utilizing genetic engineering for military purposes, something which no country had tried before. This would also satisfy his desire to ensure the United States Armed Forces remained superior to those of its rival nations. Masrani and Dearing remained unaware of Hoskins’s motives, though Dr. Wu knew about his intent and agreed so long as he continued to get funding from the Lockwood Foundation courtesy of Lockwood’s financial manager Eli Mills.

Despite the financial difficulties behind the scenes at Jurassic World, the park continued to flourish in the public eye. It often saw more than twenty thousand visitors per day, with attendance peaking during the summer and winter holidays. The number of species on exhibition greatly increased as attractions opened or changed species over time; in addition to the dozen or so animals exhibited at any given time, there were over two thousand species of de-extinct plants as well as many smaller animal species. The two biggest attractions in terms of species were the Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops, though others such as the mosasaur were extremely popular as well. Traditional electric fences were mostly eschewed by 2014, being replaced by invisible fence technology designed to interact with the animals’ RFID chips and tracking implants to keep them within designated zones.

The Indominus rex was given a limited reveal on Simon Masrani’s blog in January of 2015, though he was unable to come see the animal until December. Only one individual survived; the other was cannibalized by its sister. The paddock for the hybrid creature was nearly ready for it in the spring, but security concerns delayed its exhibition by months. It was originally planned for May, but was then delayed until July; its actual exhibition date was moved until January 2016. Six weeks before the new opening date of its paddock, Simon Masrani was finally able to visit the island. He arrived on December 22, the same day that Verizon Wireless agreed to sponsor the Indominus attraction.

During an inspection of Paddock 11 where the Indominus was being held, the animal attempted to escape and hid from its caretakers after clawing up the wall of its paddock. When thermal sensors failed to detect its lowered body temperature, the claw marks were assumed to mean that it had escaped; Dearing attempted to track it via the Control Room while Owen Grady, without her advising him to do so, took two workers into the paddock to investigate. The animal, of course, was still inside and blocked their escape route. Paddock supervisor Nicholas Letting opened the large gates to escape, which permitted the Indominus to leave the paddock before Control Room staff could close them remotely. Grady was the only survivor out of the three staff members he took to investigate the paddock. Despite his investigation being the reason for the animal’s escape, Dearing was mostly blamed for the incident.

ACU and other divisions of InGen Security attempted to recapture the animal over the course of the day, resulting in heavy casualties. Simon Masrani himself attempted to shoot the creature down after discovering its true nature from Dr. Wu, but was killed during a breach in the Aviary. After this incident, escaped pterosaurs caused numerous tourist and staff injuries on Main Street, as well as some fatalities. The island was evacuated after the pterosaurs were subdued by ACU. Hoskins made an attempt to kill the Indominus using I.B.R.I.S. raptors, which also failed; all but the eldest of the raptors died over the course of the night and numerous InGen Security personnel including Hoskins died as well. Henry Wu was evacuated by one of Hoskins’s contractors and brought to the Lockwood estate where he would be sheltered from legal inquisition. The Indominus was eventually killed at the Jurassic World Lagoon after Jurassic World staff used the Tyrannosaurus in a last desperate attempt to drive the hybrid back.

Most of the guests and staff were evacuated by the end of December 22, and Isla Nublar was abandoned again. The island was put under United Nations quarantine following the events of 2015. However, the island was not truly empty; during the evacuation, the six attendees at Camp Cretaceous became lost in the park and were accidentally left behind.

2016-present: Nature reclaims the island

After the 2015 incident resulted in the permanent closure of Jurassic World, the animals were mostly left to roam freely on the island. Since they had been primarily restricted by their tracking implants, they were not inhibited by electric fencing and could travel as they pleased. The pterosaurs remained near the island, not yet venturing as far as they were able. Animals that were kept in physical paddocks, including the younger Tyrannosaurus, were never freed and thus likely starved to death.

Despite the security, human intrusions did occur on the island. InGen Security removed a Troodon specimen named Jeanie for use in I.B.R.I.S. during late February or early March (she was returned a week later), and poachers landed illegally on Isla Nublar during mid-to-late March. This lead to the trophy killing of at least two dinosaurs including a Sinoceratops and a Baryonyx. The yacht used by the poachers was eventually commandeered by the Camp Cretaceous castaways after a few unsuccessful escape attempts; their success followed several other incidents, notably including the extinction of Scorpios rex, over the course of six months. In June 2016, mercenaries hired by Eli Mills landed on the island to retrieve an Indominus bone sample to continue Wu’s research. During this operation, the Mosasaurus was accidentally released into the open ocean, and a laptop containing valuable hybrid genome data was destroyed.

Isla Nublar had been able to support its de-extinct inhabitants between 1993 and 2002 without much difficulty due to their smaller population numbers, but after 2015, there were hundreds of large creatures living on the island. This was considerably more than the twenty-two square miles could keep fed and housed, and animals began to die off. Human intervention on the island was minimal, as it was kept under quarantine by the Costa Rican government and Masrani Global Corporation. The U.S. government was also involved with the island, raiding the Hammond Creation Laboratory among other facilities used by Henry Wu as part of an investigation into bioethical misconduct by the geneticist.

Illegal tourism also flourished around the island as had once happened near Isla Sorna. One such tour by helicopter passed over Mount Sibo in September 2017, seven months after tectonic activity between the Cocos and Caribbean Plates opened up magma chambers beneath the island. The passengers witnessed magma in Mount Sibo’s crater and reported this activity to the Costa Rican Institute for Volcanology. Some evidence suggests that geothermal drilling on Mantah Corp Island, located nearby, may have contributed to the local destabilization of the Middle America Trench subduction zone.

Throughout 2017, Mount Sibo had gradually become more active. In the northern part of Isla Nublar, heightened temperatures were causing plant life to catch fire. Pressure continued to build up underneath the volcano, with only limited amounts of gas and ash being released in minor eruptions. Nonetheless, these substances were released in enough quantity to seriously threaten Isla Nublar’s northern region. Ashfall posed a respiratory hazard, with increased risk for herbivores as they consumed plants that were covered in ash. Hydrogen fluoride at higher altitudes threatened mountain-dwelling animals, and outgassing of sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide caused the rivers to become acidic. Toxic cyanobacteria blooms occurred in water sources such as the Jungle River due to this outgassing, which killed local fish; this caused a trophic collapse which brought many species close to extinction.

By early 2018, nearly all scientific monitoring of Isla Nublar had ceased as Costa Rica withdrew equipment and personnel away from the island. It was estimated to erupt on or around June 22 of that year, and the dinosaur population continued to drop. International debate centered around what, if any, action to take regarding the Mount Sibo situation. De-extinct animal rights activist organizations, led by the Dinosaur Protection Group, endorsed relocating all the animals to a safer location; however, most governmental organizations opposed the proposal.

With all the government-provided security having abandoned Isla Nublar, poachers and other invaders were free to land on the island. Mills and Wu were responsible for two major incidents on the island during that period of its history. The first was a botched attempt at retrieving genomic data from the NMS Center on February 17, which suffered heavy casualties despite succeeding. The second was perpetrated by a mercenary group led by Ken Wheatley in mid-June. Beginning shortly before the U.S. Senate decided on a non-action policy, the organization collected numerous animals at the behest of Eli Mills in order to sell them to fund Wu’s research. On June 22, the U.S. government made its final decision not to act, and the DPG was enlisted by Benjamin Lockwood to assist with what he believed to be a rescue mission. Owen Grady was also recruited in order to help them track down and capture the last surviving Velociraptor antirrhopus masranii, Blue, an integral part of Wu’s continued research.

The supposed rescue operation occurred on June 23, with specimens of most of the surviving species being removed from the island via the S.S. Arcadia. Mount Sibo’s magma chamber was breached around midday, resulting in an explosive eruption which caused massive damage to the island. Along with de-extinct life, Isla Nublar’s modern animal and plant species were harmed by this eruption, but no thorough assessment of the island’s ecosystem has been made since.

Based on a live feed provided by the DPG website, Mount Sibo remained continuously active since its eruption on June 23, 2018 until early 2022. Much of Isla Nublar was burned or otherwise damaged by volcanic activity, returning the island to its primal state.

Volcanic activity is now subsiding, allowing plant life to grow back. Surface temperatures at Mount Sibo remain elevated but tolerable to local flora species. Hardy terrestrial creatures and coastal marine life probably survived these events, and as activity on the island calms, a new ecosystem will begin to establish itself.

Cultural Significance

Isla Nublar was continuously inhabited by Indigenous Americans for thousands of years, supporting a flourishing community based on fishing and goat-herding. The isolated location of the island 120 miles from the nearest mainland meant that they avoided most attention from Europeans; the island was discovered by the Spanish in 1525, but was not colonized. In fact, it avoided being used by Europeans almost entirely until the early 1980s when InGen became interested in it. This means that while most Indigenous American societies were decimated by invasion and colonization between the 16th and 19th centuries, the Tun-Si and other islanders remained unharmed until the late 20th.

InGen leased the island from the Costa Rican government for an increased price in 1985, resettling its people onto the mainland over the next two years. Costa Rica had increased their asking price with the help of a former Tun-Si awa of the Cruz family; John Hammond and InGen agreed to this price as they were won over by the allure of the isolated tropical island. Isla Nublar was then used as Site A for the Jurassic Park project, which introduced nonnative de-extinct organisms to the environment. Jurassic Park, of course, failed in 1993 due to an act of sabotage from within the company, forcing InGen to abandon the locale after a cleanup operation in 1994 deemed it beyond recovery.

Isla Nublar’s existence was not even known to many people outside of InGen at the time. It was often left off maps of the area due to magnetic anomalies surrounding Mount Sibo, which made mapping and navigation difficult. As the island is quite small and was of no economic or political importance, it was simply neglected. Jurassic Park survivor Dr. Ian Malcolm spoke openly about his experience there in 1995, but was not widely believed due to the outlandish nature of his tale, the lack of corroboration, and a smear campaign against him led by InGen’s Peter Ludlow. Two years after this, Malcolm was vindicated by the incident in San Diego involving a male Tyrannosaurus and its offspring, but this only brought Isla Sorna into the public eye. Isla Nublar, on the other hand, remained mostly out of the spotlight; in fact, many members of the public confused the two islands, believing that Jurassic Park had been on Isla Sorna rather than Isla Nublar.

Isla Nublar was eventually acquired as part of Masrani Global Corporation’s purchase of InGen in 1998, so it traded hands once again. Now, it was owned by Simon Masrani, the son of Hammond’s friend Sanjay Masrani. Plans to resurrect Jurassic Park were underway almost immediately, with construction beginning in 2002. Masrani faced an obvious problem; the original Jurassic Park had been a corporate disaster involving the deaths of multiple people, and he could not simply pretend it never happened thanks to Malcolm’s very public description of the incident. Malcolm’s testimony did have a weakness, however: his knowledge of what actually happened was fairly limited, as he spent most of the incident in a wounded state under the influence of morphine. His knowledge of other events would have been secondhand, told to him by the other survivors and therefore incomplete and unreliable. Masrani and his company took advantage of this, whitewashing the incident to remove the gorier and more worrying aspects and ensuring not to release Dennis Nedry’s name. Public knowledge of the incident was minimal, and Isla Nublar’s bloody history was reduced to a mysterious tale surrounded by urban legends.

Between 2002 and 2015, Isla Nublar served as a beacon for scientific research, education, and entertainment, as well as an emblem of InGen Security. The outline of the island itself became instantly recognizable, and Isla Nublar’s fame surpassed that of once-favored Isla Sorna. The Tun-Si people were able to return to their home as well, living in a reservation protected by Masrani Global where they could resume their traditional way of life.

These factors all led up to the 2015 incident at Jurassic World, which was immediately used by the park’s critics as evidence against the usefulness and safety of de-extinction and genetic engineering. Efforts were made by activists to turn the blame against Masrani Global Corporation’s administration, but many people still found it easier to blame the animals and portray them as monsters. Isla Nublar’s reputation took a turn back toward darker opinions, and as Mount Sibo became active in early 2017, the island became embroiled in controversy. Activist groups demanded that Masrani Global hold itself accountable for the animals’ safety and that the U.S. and Costa Rican governments uphold the principles of the Gene Guard Act, but a great many powerful individuals and governmental organizations opposed this proposition. Even Dr. Ian Malcolm spoke out against the idea of rescuing Isla Nublar’s inhabitants, referring to the impending eruption as a fortuitous, if saddening, event. Critics hoped that Mount Sibo would essentially give them a clean slate with regards to genetic engineering, eliminating what they considered to be dangerous scientific accomplishments.

For several years, activity at Mount Sibo showed no signs of stopping or even slowing. It was not until early 2022 that the volcano began to calm, and plant life began to regrow on the island. No efforts to reestablish a human presence have been made yet; however, as Isla Nublar’s ecosystem slowly regenerates, the island may once again become hospitable to human life. When that time comes, the Tun-Si people may be able to return to their homeland.

Ecological Significance

Isla Nublar was inhabited by a large number of indigenous animals and plants, as well as a number of introduced and invasive species. Most of its inhabitants were birds, including the toco toucan, collared aracari, scarlet macaw, brown pelican, and Franklin’s gull. Hundreds of seafaring birds nested along its coastline (and many probably still do), and countless more bird species lived in the inland forests before they were burned during the 2018 eruption of Mount Sibo. These include a species of Corvus, the only member of its genus in Costa Rica. Introduced birds, such as mallards and kookaburras, were brought to the island over time.

Mammals also inhabited Isla Nublar in surprisingly large numbers for an offshore island. These included species often found on the Costa Rican mainland, such as collared peccaries and mantled howlers, as well as at least one endemic subspecies of tufted deer (otherwise found only in Asia). In the game Jurassic World: The Game, the Central American agouti can be seen as a fodder animal; it is unclear if it is intended to represent native or introduced wildlife. Introduced and invasive mammals included goats (introduced thousands of years ago by the Bribri people) and brown rats (introduced in the 1980s and 1990s by InGen), as well as domestic pigs and cattle. Rats have likely survived the ecological collapse following Mount Sibo’s 2018 eruption, and goats may have survived as well, but the state of Isla Nublar’s mammalian fauna has yet to be reviewed in recent times.

The apex predator of Isla Nublar, the largest predator known on the island, was the common northern boa. Other snakes likely lived on the island, but none as large as this reptile. Growing to lengths of up to 3.7 meters (although insular populations tend to be dwarfs), it was large enough to consume most of the native prey items on Isla Nublar. Its status of apex predator persisted until humans arrived on the island thousands of years ago, and was further diminished in 1989 with the introduction of large theropod dinosaurs.

At the other end of the food chain were small arthropods, such as dragonflies, sawflies, beetles including ladybirds and fireflies, cockroaches such as the American cockroach, lepidopterans such as sphinx moths, metalmarks, and the Julia heliconian, centipedes, dipterans including mosquitoes and calyptrate flies, and ticks, which lived in the forests and grasslands of the island and were fed upon by the smaller vertebrates. Large leeches were known from freshwater wetlands. These are probably among the few animals that still survive on the island after the eruption of Mount Sibo in 2018. Parasitic invertebrates that rely on larger animals as hosts, such as hookworms and tapeworms, were known prior to the eruption but have likely now decreased in number, other than those which can infect the smaller animals or seagoing creatures that have survived on the island.

Most of Isla Nublar’s ecology was forest, with cloud forests in the mountains and rainforest in the lowlands. There were also some areas of grassland and low-growing shrubs, though rocky dry landscapes were relatively uncommon prior to the 2018 eruption. Some marshes existed in the south and along other coastlines. Plant life was once abundant all over the island before the 2018 eruption, though a great many introduced species have occurred since 1988. These include the destructive Moreton Bay fig tree, which is known for strangling other tree species to death as a part of its growth progess, fast-growing and habitually invasive bamboo and elephant grass, and flowering plants such as the West Indian lilac. The latter is harmful to animals; other harmful species introdued include painter’s pallete, poison ivy, and bracken. The monkey puzzle tree, native to Chile and Argentina, was introduced by 2004; on the other hand, the banana was introduced to the island considerably before this, likely prior to InGen’s acquisition of the island. Mangoes could be found there according to Jurassic World: The Game; its prequel Jurassic Park: Builder describes sweet wormwood, which is native to Asia, as having been deliberately introduced. Eucalyptus was known there in 1993 in the central part of the island. Native plants, including palm trees, kapok, poor man’s umbrella, and golden dewdrop berries, were still sometimes seen before 2018. Heliconias were introduced in the 1990s as decorative plants, but the species used were already native to Costa Rica and thus probably did not have a detrimental effect on the island’s ecosystem. Redwoods, either the modern coast redwood or some extinct relative, were introduced to the island’s north as well as the central Jurassic World park areas and were fully grown by late 2015. Following the 2018 eruption and subsequent volcanic activity, much of the forest environment has been decimated, but as of 2022 is beginning to grow back. How much of the surviving flora is native and how much is introduced has yet to be determined.

In such a damp environment, numerous kinds of fungi likely exist; at least one fungal species found on the island could cause skin infections in de-extinct animals, but whether it was native or introduced is not known. Isla Nublar’s fungal ecology is poorly studied. Its microbiota is similarly poorly known, with research only occurring where it was relevant to de-extinction research or human health. A species of freshwater microalga can be found in flooded lava tubes, and is noteworthy for its bioluminescence. Since it lives in dimly-lit environments, it must have a source of energy other than photosynthesis, but what method it uses is not known. A species of cyanobacteria is found in many freshwater sources as well, and was notably involved with a dinosaur health issue in 2003-2004 after mutagens were introduced to its environment. Other more common species such as E. coli are known from Isla Nublar. Despite the minimal information known about the fungal and microbial biology of Isla Nublar, they form the foundation of its ecology here as they do anywhere else in the world. As the island recovers from its recent volcanic activity, these organisms will be crucial to the establishment of new ecosystems.

Marine life was and probably still is abundant in the surrounding waters. Species such as damselfish and the teardrop butterflyfish were still seen in 1993, despite competition with introduced species such as the Atlantic blue tang. InGen also introduced freshwater fish, such as the common carp and blue discus, during the 1980s and 1990s; these may still exist in Isla Nublar’s inland waterways, though volcanic pollution likely decimated their populations in 2018. Native freshwater fish are unknown, and probably unlikely so far from the mainland. The introduced fish probably feed on various species of invertebrates. In the surrounding seas, humpback whales, yellowfin tuna, green sea turtles, and great white sharks are commonly seen; their local presence implies the existence of many sorts of fish and krill, macroalgae and cnidarians, and pinnipeds to sustain these megafauna. Mackerel are caught in the surrounding waters. Various kinds of kelp and other macroalgae grow on the seabed where it is shallower, and a few kinds of coral such as staghorn occur along the coasts. On the seabed one can observe chocolate chip sea stars, titan acorn barnacles, and Central American rock-boring urchins. The favored prey of these invertebrates, including bivalves, plankton, and macroalgae respectively, are abundant in Isla Nublar’s waters.

Since 1988, de-extinct animals and plants as well as genetically engineered species have been introduced to Isla Nublar. The known animal species resurrected or created on the island are listed below, with the dates at which it is believed that they were first introduced to Isla Nublar:

- Triceratops horridus – 1988

- Brachiosaurus “brancai“ – 1988

- Parasaurolophus walkeri – 1988?

- Tyrannosaurus rex – 1989

- Compsognathus “triassicus“ – 1990s?

- Tylosaurus proriger – 1990s?

- Dilophosaurus “venenifer“ – 1991-1993

- Velociraptor “antirrhopus nublarensis“ – 1991-1993

- Gallimimus bullatus – 1992-1993?

- Troodon pectinodon – 1992-1993

- Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis – 1993

- Pteranodon longiceps “hippocratesi“ – 1993?

- Ankylosaurus magniventris – 2004

- Pteranodon longiceps “masranii“ – 2004

- Corythosaurus casuarius – 2004-2005

- Spinosaurus aegyptiacus “robustus“ – 2004-2005

- Ceratosaurus nasicornis – 2004-2005

- Velociraptor “antirrhopus sornaensis“ – 2004-2005

- Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum – 2004-2005

- Stegosaurus stenops “gigas“ – 2004-2005

- Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis – 2004-2005

- Microceratus gobiensis – 2004-2014

- Baryonyx walkeri – 2004-2005

- Carnotaurus sastrei – 2004-2009

- Edmontosaurus annectens – 2004-2014

- Pteranodon longiceps “longiceps“ – 2005

- Apatosaurus ajax – 2005-2010

- Dimorphodon macronyx – 2005-2014

- Metriacanthosaurus parkeri – 2005-2014

- Suchomimus tenerensis – 2005-2014

- Parasaurolophus tubicen – 2005-2014

- Segisaurus halli – 2005-2015

- Styracosaurus albertensis – 2005-2015

- Euoplocephalus tutus – 2005-2015

- Coelurus fragilis – 2005-2015

- Stygimoloch spinifer – 2005-2011

- Allosaurus jimmadseni – 2005-2015

- Pachyrhinosaurus sp. – 2005-2015

- Deinonychus antirrhopus – 2005-2015

- Lesothosaurus diagnosticus – 2005-2015

- Mosasaurus maximus – 2006-2007

- Scorpios rex – 2009

- Velociraptor “antirrhopus masranii“ – 2012

- “Troodon formosus“ – 2012?

- Indominus rex – 2012

- Sinoceratops zhuchengensis – 2014-2015

- Tarbosaurus bataar – 2015?

- Mesosaurus tenuidens – 2015?

- Dimetrodon grandis – 2015?

- Nasutoceratops titusi – 2015?

- Ouranosaurus nigeriensis – 2015?

- Monolophosaurus jiangi – 2015?

- Peloroplites cedrimontanus – 2015?

- Teratophoneus curriei – 2015?

There are other animal species which may have been cloned, such as Deinosuchus, and numerous species that existed only as genomes or embryos on the island. An unknown number of small de-extinct animals were created there; while it is not film-canon, Jurassic World: The Game claims that these included Triassic beetles belonging to the family Cupedidae. Smaller marine life is known to have been brought back to extinction between 2003 and 2015, kept in the Jurassic World Lagoon, and over 2,000 species of Mesozoic plants are known to have been recreated, including a Cretaceous veriforman and Jurassic vermiform. Hybrid plant species were also grown there, including hybrid coffee beans and grasses.

All of these de-extinct species have spent some amount of time in the wild, either between June 11, 1993 and April 2002 or between December 22, 2015 and June 23, 2018. During the second wild period, the island’s animal population was considerably larger than could comfortably survive in twenty-two square miles; this led to many species, such as Edmontosaurus and Metriacanthosaurus, falling back into extinction. On June 23, 2018, Mount Sibo erupted and caused the near-complete destruction of Isla Nublar’s ecosystem including both modern and de-extinct life. As of early 2022, activity had subsided enough for plant life to begin reestablishing throughout the island.

Behind the Scenes

Map Discussion – Original JPLegacy Transcript – Edited 2018

Park Tour Map

This is the official map from the Official Souvenir Magazine and seen on the Brochure in the film, however, Herrerasaurus was edited to be in it’s current position from the transfer from Brochure to the magazine. Although cartoonish, and it contradicts the paddock structure seen in the film on the computer screens as the fences are going out, this map is considered to be canon and based on generalization above all else.

Road Labels:

Visitors’ Center

Access Road

Tour Road

Right Key (Dinosaurs):

Brachiosaurus

Gallimimus

Triceratops

Parasaurolophus

Proceratosaurus

Metriacanthosaurus

Segisaurus

Tyrannosaurus Rex

Velociraptor

Dilophosaurus

Herrerasaurus

Baryonyx

Left Key (Building Guide):

Visitors’ Center

Port

Heliport

Electric Fence

Tour Road

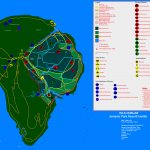

TellTale Map

TellTale makes some adjustments to the position of the paddocks, additional areas, and the tour road. This isn’t completely off, really, and locations are generally within the same area, save for a few exceptions which make it a bit more consistent with the Paddock shutdown map. So in essence this is within the error margin we originally determined back when we did our own Isla Nublar map of “generalization”. By no means does it serve as an exact scale for where things are, but it is considered a somewhat general guide of where things/events are placed like the tour map. Any inconsistencies can be safely ignored due to the simplicity of both maps.

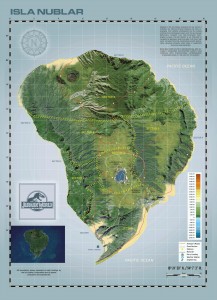

Jurassic World Park Map

The Nublar map under Masrani ownership differed in several topographical details. The park’s previous infrastructure appears to have either been removed or integrated to fit the new park, as several of the features on the map overlap with the previous paddocks. The lagoon and the boardwalk serve as the hub of activity in Jurassic World, with most activities and access to transportation located there. The public entrance to Jurassic World is through the Ferry Landing in the extreme south of the Island. The Monorail transports guests from the ferry to the Isla Nublar Hilton, although there are four other monorail stops on the boardwalk. The monorail provides guests with access to all of the parks attractions and facilities.

The Nublar map under Masrani ownership differed in several topographical details. The park’s previous infrastructure appears to have either been removed or integrated to fit the new park, as several of the features on the map overlap with the previous paddocks. The lagoon and the boardwalk serve as the hub of activity in Jurassic World, with most activities and access to transportation located there. The public entrance to Jurassic World is through the Ferry Landing in the extreme south of the Island. The Monorail transports guests from the ferry to the Isla Nublar Hilton, although there are four other monorail stops on the boardwalk. The monorail provides guests with access to all of the parks attractions and facilities.

The north of the Island is designated the ‘Restricted Zone’, and access is most likely restricted to guests. In addition, there appears to be a physical barrier separating this area from the area of the park accessible to guests. The park’s geothermal power station is also located in this area. Also we have gotten our hands on brochure map from an extra that starred in the fourth film. We are going to keep their identity as anonymous for their privacy, but we are very grateful for their contribution to have this other look at the differences between Jurassic Park and Jurassic World.

Another more detailed map was released for the film, also as poster and lithograph. This one details the sectors and how they are divided across the island, the map even lists the ACU substations on it with the little blips across it. By far this map is the most detailed out there of the Jurassic World layout. Unfortunately there is no explanation evident for the drastic changes in geography of the island from 1993 to 2015.

Another more detailed map was released for the film, also as poster and lithograph. This one details the sectors and how they are divided across the island, the map even lists the ACU substations on it with the little blips across it. By far this map is the most detailed out there of the Jurassic World layout. Unfortunately there is no explanation evident for the drastic changes in geography of the island from 1993 to 2015.

Another map made in 2018 by digital artist SteamBlust, is essentially another revision of the newer Jurassic World map that came out in 2015 and is in the form of the more detailed map released from the film that would probably be used in ACU substations or the control room of the park itself. This moves the lagoon closer to the ocean rather than being in-land. Per conversations on Twitter with Colin Trevorrow when people asked about this, it was always meant to be this way. The Jurassic Park island, in particular Nublar, has had a lot of different realizations of it over the years. So this in itself, is no different than what the fandom had been dealing with in terms of maps being based on nothing more than generalities and loose associations alone. See the Jurassic Park Legacy map as well as the explanation and analysis of how TellTale’s game affected the map itself as well in the next section after this.