Biosyn Valley (Italian: Valle di Biosyn) is a relatively large, mostly uninhabited valley of the Dolomite Mountains located in the Italian regional decentralization entity of Pordenone. It was privately owned by the foreign corporation Biosyn Genetics from the 1990s until early 2022, at which point the United Nations took on a supervisory role. Its original name was probably not “Biosyn Valley,” but any name it had before being purchased is not canonically known. The closest inhabited area is the Piave Valley, which shares some mountain borders with Biosyn Valley.

In the modern day, Biosyn Valley is known for being the site of Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary, which houses fifty or more species of de-extinct animals sourced from around the world. Between 2018 and 2022, Biosyn Genetics was contracted by the governments of several countries to ship de-extinct animals that had been collected from the wild into the valley, where they would be housed away from inhabited areas and used for biopharmaceutical research. Despite challenges in 2022 due to corporate corruption, the sanctuary is still functioning. This valley functions as a wildlife refuge for de-extinct animals that either cannot be allowed to roam in the wild or are significant for research purposes.

There are two major structures within the valley: Biosyn’s headquarters at the northeastern end, and the largest privately-operated hydroelectric dam in Italy at the southwestern end. Also in the southwest are disused amber mines, and just upriver of the dam is an airfield. The sanctuary contains several research outposts which are connected by a hyperloop system.

Name

While in the modern day Biosyn Valley is named after the company that owns it, Biosyn Genetics, it probably had a different name before being sold by the Italian government in the 1990s. Sadly, its original name has not been given in canon.

Translated into the local language, the valley would be called Valle di Biosyn, though this name has not been used in canon.

Location

Biosyn Valley is a valley of the Dolomite Mountains, a part of the Southern Limestone Alps in northeastern Italy. On its northern side it borders the Marmarole mountain group. It is located on the border of the regional decentralization entity of Pordenone (a province of the Friulia-Venezia Giulia region) and the province of Belluno (a province of the Veneto region).

Biosyn headquarters are located at 46°30’36.7″N, 12°20’26.6″E. This marks the northeastern end of the valley, and places it upon the flanks of the mountain Cimon del Froppa. In real life, this mountain is just north of the Piave Valley, which is not shaped in quite the same way as Biosyn Valley and therefore is a different geological feature. However, the Piave Valley does also contain an enormous dam, the Vajont Dam. Unlike the Biosyn Valley dam, the Vajont Dam is not operational because it was involved with a megatsunami in 1963 which killed over 2,500 people.

Description

Biosyn Valley’s precise size has not been described canonically, but it can be estimated. Knowing that the tallest mountain nearby is roughly three thousand meters in height, and considering that the valley is about three times as wide in any direction as the highest nearby mountain is tall, the valley’s width is approximately nine thousand meters, giving it an area of roughly 63.65 square kilometers or 24.56 square miles. For reference, this is slightly larger than Isla Nublar, which has an area of 22 square miles.

It is large enough to contain a modest ecosystem but small enough that larger artificial structures throughout it can be plainly seen from any point within it. There are nineteen major mountains that form the valley’s border, with the peaks of the northeastern mountains being generally higher than the southwestern ones. The northeastern valley floor is also generally higher in altitude than the southeast. Its mountains are all in the range of roughly 2,500 to 3,000 meters (close to 8,200 – 9,840 feet). The nearby Cimon del Froppa, at 2,932 meters or 9,619 feet, is the tallest mountain in the Marmarole group of the Dolomites in real life and appears to be so in the fictional Biosyn Valley area too.

The valley is loosely circular in shape, unlike many of its neighboring valleys which are longer and narrower. Its central area is quite flat, sloping gently into foothills before rising up into the mountain peaks that ring it. Despite the fertile and amenable land in the valley center, it has few navigable passes leading in or out, so it has not seen much long-term human habitation in recent history. One of the main passes is currently blocked by a large reservoir and hydroelectric dam; even without the dam in place, the river would cascade approximately 800 feet (244 meters) from the mountains into the valley below, making it nearly impossible to traverse on foot. A slightly more navigable pass is located to the northwest.

At least two major river tributaries flow into Biosyn Valley from the surrounding mountains, originating from alpine meltwater. They probably flow deeper in the spring as temperatures rise. One tributary originates in the northeast, descending from mountains near Cimon del Froppa and flowing south. The other is the one dammed for hydroelectric power, located at almost the opposite end of the valley and flowing north. Based on the size of the dam that holds it back, the southeastern reservoir contains somewhere in the range of 150 million cubic meters (5,297,205,000 cubic feet) of water; the tributary from the southeast is the larger of the two. Smaller tributaries may form from meltwater and runoff. The main river is oriented in a northeast-southwest line, running roughly straight across the valley and collecting in two large lakes. The northern lake is the bigger of the two. Biosyn Valley has no areas along its border that are geographically low enough for the river to exit; it is a cryptorheic basin, with its waters seeping underground and reemerging as springs in the Po Valley farther to the south. From here the water joins with other rivers which flow to the Mediterranean Sea.

The valley contains a few different kinds of environments. High in the mountains there are alpine tundras and meadows, with many of the sheer cliffs simply consisting of bare rock that provides little purchase for animal or plant life. The rock of the Dolomites is sedimentary, having formed from sand and silt laid down by prehistoric rivers that built up over time before being uplifted into the mountains we see today. As the mountains’ name suggests, dolomite is a common mineral found here, along with abundant limestone, sandstone, and marl. However, there is also a smaller amount of ancient igneous rock, although the area has not experienced volcanic activity in many millions of years. Most of the bedrock originates from the Triassic period; this valley is particularly rich in amber dating from the Mesozoic, though poor iron content makes it less likely to preserve ancient DNA from that age. The surrounding mountains are from the Marmarole group, some of the wildest mountains of the Dolomites and considered extremely difficult to scale.

Below the treeline, which is located 2,100 meters (6,890 feet) up the mountains at its highest, coniferous trees start to appear and remain dominant all the way through the foothills into the lowlands. Biosyn Valley’s floor is heavily forested all the way across, with few large clearings or grassland areas; in recent times browsing from de-extinct megafauna has cleared some forest, but far from all of it. In early 2022 the forest was damaged by a large wildfire, especially in the northeastern area where the fire began. However, a large amount of forest survived. In the lowland areas, the climate is temperate and often damp, with fog being common in the forests due to transpiration. The valley floor is considerably lower than many of its neighbors, so the temperature even in the winter does not drop below freezing in the lowlands. Though its precise elevation is not known, based on surrounding real-life geography its floor probably sits at roughly 700 meters (2,297 feet) above sea level or slightly lower. Biosyn Valley is climatically isolated from nearby valleys. Using the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system, Biosyn Valley can be described as either oceanic or humid continental, bordering on subtropical, with hot summers and rainy winters. Thunderstorms are common and can sometimes roll in quite suddenly, with the mountains making their approach hard to detect from the ground.

Between rainfall and meltwater, Biosyn Valley is well-irrigated by its rivers; along with the two main tributaries, smaller runoff streams descend from the mountains and provide a reliable source of fresh, clean alpine water. The freshwater environments of Biosyn Valley are untainted by pollution thanks to the valley’s remote location and climatic isolation. Small lakes and ponds are present across the valley, fed into by the mountain rivers, with the largest lake being located roughly near the valley’s center and a slightly smaller lake located in the southern area. Wetlands fed by smaller streams are sometimes seen in the foothills.

Water is also responsible for the valley’s most obscure environment, karst geography. Karst is a kind of landscape that forms when water erodes soluble rock, creating features such as sinkholes and caverns. Most caves in Biosyn Valley are dripstone caves, containing water-formed speleothems such as stalactites and stalagmites. These caves have been carved out by running water over thousands of years since the most recent ice age, and many still contain small streams; others are flooded but stagnant, containing ponds with no inlet or outlet. Flooded caves are more common at lower altitudes where water can drain no further. Some of these water pools may have remained undisturbed for a long time, unable to evaporate or drain. At higher altitudes, it may be possible to find ice caves, which are common in the Limestone Alps where the Dolomites are located.

Artificial infrastructure in the valley is mostly unobtrusive, with the largest buildings being the hydroelectric dam and Biosyn headquarters, which are at opposite ends of the valley. Both are built in the mountains, though headquarters is in the foothills rather than the alpine tundra, and each one is built over a tributary of the valley’s river. Across the valley floor are a few smaller buildings, most of which are research outposts and power relay stations. Most of the power grid is built underground, alongside the hyperloop tunnels which connect the facilities. Unpaved access roads are present on the ground above, but are seldom used; the infrastructure of the amber mines is almost completely disused. The mines are still accessible via hyperloop, but the ground-level entrance is blocked by an electronically-locked gate. Until recently these were the only ways to access the amber mines, though in 2021 or early 2022 maintenance work accidentally broke through into an adjacent cave system. Few to no physical barriers are built in the valley, with animal movement instead restricted using invisible fence technology linked to their neural interface devices.

History

Prehistory

The rocks that underlie the area where Biosyn Valley is located are mainly sedimentary in origin, having been lain down by water millions of years ago; limestone is the most common kind of bedrock here, and it was created during the breakup of Pangaea during the early Triassic period. At that time, the land that is now the Alps (including Biosyn Valley) was underwater, the flooding of eastern Pangaea having turned it to continental shelves and inland seas. From these oceanic waters, the sediment that would become the valley’s bedrock was deposited.

Further limestone deposition occurred during the Jurassic period, which had high sea levels like the Triassic. But about one hundred millions years ago, during the middle Cretaceous, the African and Eurasian plates ceased their divergence and began to come together again, pushing up the land between them. Soft marine sediments were folded, rising up above sea level and gradually forming into mountains. As the Mesozoic era ended and the Cenozoic began, the mountains were pushed higher and erosion carved out dramatic peaks; eventually, closer to the modern day, some of these mountains grew tall enough to sustain snow and ice caps, leading to the formation of springtime meltwater streams which increased erosion. Tectonic thrust continued throughout the Cenozoic era, further developing the region. Later in the Cenozoic, ice ages occurred, with glaciers forming at lower latitudes than normal. These glaciers carved out valleys, and their enormous weight pushed down the land they sat upon.

Biosyn Valley is an unusual shape, being almost circular rather than linear or u-shaped like most valleys in the area. At the moment, not much is known about how it formed, but it was likely due to some combination of tectonic uplift, glacial pressure, and water erosion. The valley is a cryptorheic basin, with no obvious route for outflow of its water. Instead, the water seeps into the ground to reemerge farther south. If the land was occupied by a glacier during the ice ages, the melting ice probably flooded the valley, as the glacier had nowhere to go any farther downhill from there. Over time the water drained away through the earth. Since the ice ages, Biosyn Valley’s surrounding mountains have remained a source of runoff, and two major river tributaries flow into the valley. Over thousands of years, meltwater has carved out caves beneath the mountains. Since dolomite is less soluble in water than limestone, the differing kinds of rock determine how karst landscapes are likely to form in Biosyn Valley. Amber is common in the valley, having formed from the resin of ancient trees that grew during periods of time when the land was above sea level. If globs of resin became buried in the ground, they could fossilize, becoming amber.

About 40,000 years before the modern day, early humans arrived in Europe. Whether any of these ancient people, or their close relatives the Neanderthals, ever lived in Biosyn Valley is unknown at this time.

2000 BCE-1990 CE: Italian history

Humans are known from the area surrounding Biosyn Valley sometime before 2000 BCE, though there is no direct evidence that they inhabited the isolated valley itself. Hunter-gatherers flourished among the rocky peaks of the Dolomites for millennia, eventually growing into distinct sedentary cultures. That region of Italy was home to the Villanovan and Alpine Halstatt cultures, the former of which were ancestors to the Etruscans. The Paleoveneti (ancestors of the Veneti) were another of the early peoples of northern Italy, developing religious practices by the fifth century BCE.

Control over the nearby areas, which are now the provinces of Belluno and Pordenone, traded hands over the centuries; it is still unclear which province Biosyn Valley belongs to, or whether ownership over the valley has changed with time. During the Middle Ages, Pordenone was controlled by the province of Treviso, while Belluno was a part of the Holy Roman Empire’s borderland, specifically the March of Verona and Aquileia. In 1233 CE, the Aquileians conquered what is now Pordenone, meaning that Biosyn Valley was certainly under the Empire’s control during this period of time. In 1278, the Pordenone region was ruled by the House of Habsburg, which controlled it until 1508. During that same time, Belluno was ruled first by the House of Carraresi, which then fell to the Republic of Venice in 1404 during the War of Padua.

Pordenone flourished economically during the fifteenth century, producing textiles, silk, wool, and ceramics, bringing traders to the region. Both Belluno and Pordenone were controlled by Venice during this period of time, with Venetian rule continuing until 1797. That year, the French First Republic invaded under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte, which led to the fall of the Republic of Venice. The area which includes Biosyn Valley was ceded to the Habsburg Empire in the Treaty of Campo Formio. However, in 1805, it was ceded to the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in the Peace of Pressburg.

What is now Pordenone came under control of Austria in 1813, while the 1815 Congress of Vienna restored what is now Belluno to Austria after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The modern-day borders of these two provinces began to take shape at this time. Both provinces finally came under Italian control in 1866, when the Kingdom of Italy unified.

The Dolomites saw action during the First World War, during which both Italy and Austria-Hungary laid out explosive charges along their front lines as they fought throughout the mountains. Mines were placed between 1916 and 1918. Along with the mines, alpine warfare along the Italian front included the construction of tunnels and shelters for the warring nations’ armies to utilize. While it is unknown whether Biosyn Valley was ever the site of any fighting during the war, the valley’s extensive cave systems could have provided preexisting underground structures for either side to make use of. Fighting took place among peaks and glaciers, and the foot paths carved out by soldiers in the war can still be seen among the Dolomites today. In 1919, the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed, and territories that had been seized by Austrian forces were ceded back to Italy.

The area which contains Biosyn Valley changed ownership again during the Second World War. In the earlier years of conflict, Italy was on the side of the Axis Powers, but signed the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies in 1943. When this occurred, the province of Belluno was annexed in all but name to Nazi Germany, which controlled the area until it was ultimately defeated in 1945. At that point, Biosyn Valley once more came under Italian rule.

Since the World Wars, this region of Italy has developed economically. Though it is known for low-income agriculture, valleys in this area are also well-known for the production of Piave cheese from local cows, which comes from an area that neighbors Biosyn Valley. The province of Belluno is also a major manufacturing center. This may have been the reason that a massive hydroelectric dam was constructed at the southwestern end of Biosyn Valley, damming a major tributary to its river system. This is still one of the largest dams in Italy, rivaling or equaling the failed Vajont Dam. However, it is unknown whether any communities were ever situated here in the long term. At one point, large deposits of Mesozoic-aged amber were found in the valley.

1990-2015: Amber mining operations

During the 1990s, the American bioengineering corporation Biosyn Genetics entered into talks with the Italian government to purchase land in the Dolomites. This valley was sold along with any preexisting infrastructure (it is also possible, but less likely, that Biosyn constructed the hydroelectric dam after purchase of the land). If any people were living in Biosyn Valley at that time, they may have been employed in the amber mines which Biosyn constructed beneath the mountains, which seem to have been concentrated largely in the south. It is also during this time that Biosyn Valley received its current name; its original name has not been given in the film canon.

While the purpose behind Biosyn’s amber mines was not disclosed to the public, they were searching for ancient DNA. In the previous decade, their corporate rival International Genetic Technologies had discovered a method for retrieving genetic material of unfathomable age from inclusions found in amber samples. Using this recovered DNA, they were able to genetically engineer and clone animals and plants which had gone extinct long before the evolution of humans. Biosyn had learned of InGen’s plans to exhibit these de-extinct species to the public and hoped to counter with a similar attraction of their own, and to this end, they excavated large quantities of amber from Biosyn Valley.

Unfortunately for Biosyn, their efforts were for naught. Although amber can extend the viability of DNA molecules for millions of years, only those preserved within particular types of iron structures can be effectively used for de-extinction, and such structures were not present in Biosyn Valley’s iron-poor rocks. Even if Biosyn had managed to recover enough DNA to utilize, InGen was still the only entity at the time which had the technology to actually turn prehistoric gene sequences into living things.

Biosyn still owned the valley, but the amber mining operation was abandoned, and the mines fell into disuse. At this point it appears no one used the valley for any purpose; its isolation likely helped to ensure that no other political or corporate entity petitioned the Italian government for ownership, so Biosyn remained the uncontested owner of its self-titled valley. In the meanwhile, InGen succeeded at opening a de-extinction theme park, which ran without major incident from 2005 until 2015. Biosyn spent that time focusing its efforts elsewhere.

2016-2022: Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary

At the end of 2015, InGen’s de-extinction park was shut down by its holding company Masrani Global due to a serious security incident that led to the deaths of several employees and park animals. The cause was not any of the park’s more high-risk de-extinct creatures, but rather a species built using revolutionary genomic techniques by InGen’s senior geneticist Dr. Henry Wu. After the incident, he vanished, and was found guilty of bioethical misconduct by the United States Congress. While this ended InGen’s dominance in the bioengineering field practically overnight, it did not immediately mean the situation was ideal for Biosyn. Their CEO, longtime employee Lewis Dodgson, had planned to build his own de-extinction park to compete with InGen’s, but now public confidence in de-extinction was at an all-time low.

To avoid frightening away investors, Dodgson had Biosyn keep a low profile in the world of genetic engineering for the time being, quietly expanding access to Biosyn Valley. If the company did not already own the enormous hydroelectric dam at the valley’s southwestern end, it purchased the structure at this point, and a new research facility came under construction at the northeastern end. This, once it was completed, would become Biosyn’s new headquarters. Dodgson hired new staff members, such as Ramsay Cole of Biosyn Communications, to run the valley facilities.

By mid-2016, Biosyn was beginning to build a genetic library of its own, beginning with assets illegally acquired from InGen’s now-abandoned facilities in the Gulf of Fernandez. While possessing complete, pre-constructed genomes would allow Biosyn to clone de-extinct species at its research facility, Dodgson wanted to begin populating the valley with live, mature specimens sooner. In 2017, he succeeded in orchestrating a raid on InGen’s remote Site B facility, and animals including a mated pair of Tyrannosaurus rex were imported to Biosyn Valley as its first generation of de-extinct life.

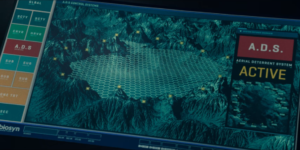

The infrastructure of the valley was built to be as non-invasive as possible, creating a naturalistic environment that the dinosaurs could roam. Across the valley floor, numerous research outposts were built, and employees could access these observation posts from underground tunnels. Using the old amber mines as a starting point, Dodgson oversaw the construction of a hyperloop which would shuttle researchers and maintenance staff around the valley at rapid speeds. Because of the hyperloop, there was less need to use the ground-level access roads, reducing disturbance and pollution from vehicles in the valley. A helipad was present at the main compound, but most aircraft would instead arrive and depart from an airfield located upriver from the dam, outside the valley proper. There were few physical barriers to restrain animal movement, and an invisible fencing system was implemented to keep them from going places they were not meant to be. This was coded into the V-55 neural interface devices which were implanted into each creature moved to Biosyn Valley. Flying animals were restricted from leaving the valley through the Aerial Deterrent System, and aircraft permitted to fly through its airspace were outfitted with ADS beacons which would keep airborne animals from approaching.

In 2018, de-extinction technology went open-source when it was sold on the black market, along with many species of animals looted from Isla Nublar. Animals that were released into the wild became a major political issue as debate raged as to whether or not these animals had rights. Dodgson stepped in, proposing that the United States government send any problem animals to Biosyn Valley—which was now being branded the Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary, a safe and humane home for de-extinct life forms. Here, they would be kept away from civilization, and in return they would act as research subjects to yield new biopharmaceutical products to benefit humanity. The government eagerly agreed, awarding Biosyn sole collectors’ rights to the animals. Other countries soon followed suit, and the intergovernmental Department of Prehistoric Wildlife aided national governmental authorities in shipping dinosaurs and other creatures to the sanctuary.

As time went on, the valley’s population grew not just in numbers but in diversity. Outside Biosyn Valley, the black market de-extinction trade was flourishing, and anyone with the means and motive could create new life forms. Often times, these animals ended up being seized by the authorities or released into the wild once their owners could no longer provide for them, and then they frequently found their way to Biosyn Valley. There is also evidence that Dodgson was trading directly with the black market through brokers such as Soyona Santos, so new species were both entering and leaving Biosyn Valley during that time. The contract pilot Kayla Watts made several deliveries of de-extinct animals to the valley during the early 2020s, allowing Biosyn to acquire specimens outside the law. And, of course, Biosyn itself now had access to de-extinction technology. They created their own species too, introducing them to the valley. By the end of the decade, Biosyn had also acquired the fugitive Henry Wu, who had spent years hiding from the authorities after the 2015 incident. In secret, he became a part of their team working on the classified Hexapod Allies program, which would revolutionize agriculture if successful.

Between 2016 and 2022, operations in Biosyn Valley proceeded largely as normal. Construction on new outposts and hyperloop tunnels, as well as ongoing maintenance on the existing infrastructure and power grid, continued over the years, and research was highly successful. The animals established themselves in the valley’s various microbiomes, forming a new ecology that displaced the existing one. To give the predators a food source other than their multimillion-dollar kin, Biosyn began importing red deer from the surrounding regions, but the herbivores were able to sustainably feed on the flourishing plant life. Aside from the deer and de-extinct organisms, no life forms were deliberately imported to the valley. Studying the animals’ immune systems led to a variety of biomedical discoveries. As of 2022, Lewis Dodgson believed that new treatments for cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and autoimmune disorders were on the horizon.

There was trouble behind the scenes, though. Some major incidents occurred and were swept under the rug, such as the disappearance of an engineer in the amber mines. Construction crews accidentally breached through one of the walls of a mine and into the adjacent cave system in which Biosyn’s Dimetrodons spent their nights. The engineer’s disappearance led to new safety protocols being put in place, though it was not until early 2022 that he was found to have been killed in an animal attack (though it was strongly suspected before this). Hexapod Allies was also facing difficulties, as the genetically-modified insects utilized in the program had turned out more virile and long-lived than expected. Some had been released deliberately by Dodgson in North America, and now Wu was scrambling to curb the swarm’s expansion before someone noticed and linked them to Biosyn. And the dinosaurs were facing problems too: as their population continued to grow, they sometimes found themselves living in uncomfortably close quarters. Biosyn had bred a male Giganotosaurus in recent years, and it grew large enough to bully the older tyrannosaurs from Isla Sorna into giving up their territory. Most of the valley’s northern and central forest areas belonged to it, though in practice it could go wherever it pleased, and often did.

Despite these ongoing problems, Biosyn Valley was viewed as a godsend by the world’s governments (who would otherwise have to deal with the de-extinction controversy themselves) and members of the public (who were either happy to see the animals safely housed and cared for, or simply glad that the animals were being removed from the wild). Complaints mainly focused on the fact that Biosyn’s profits benefited greatly from the crisis, since their responses to dinosaur conflict always resulted in good performance in the stock market. Dodgson himself believed that Biosyn was too big to fail, and that the valley would ensure their dominance in every sector they had stake in for the foreseeable future.

2022-present: Current operations

In early 2022, everything came catastrophically crashing down for Lewis Dodgson, with consequences for the valley as a whole. He had authorized a plan devised by Henry Wu to curb the proliferation of the insects released in North America, which were spreading out of control. Poachers were hired to collect two research specimens: a human clone named Maisie Lockwood, and a parthenote Velociraptor called Beta. In the meanwhile, Ramsay Cole of Biosyn Communications had discovered Hexapod Allies and realized Dodgson was corrupt, planning to expose him with the help of their resident lecturer Dr. Ian Malcolm and his colleagues Drs. Ellie Sattler and Alan Grant. A formal invitation to Sattler and Grant was approved by Dodgson, who was merely excited to have celebrity scientists bring the facility some publicity with their visit. On the same day, a new animal arrived from the U.S. Wildlife Relocation Facility, this one InGen’s oldest tyrannosaur, who fairly quickly established enmity with the Giganotosaurus.

Both Maisie and Beta were delivered successfully through Santos’s connections in the spring of 2022, but Dodgson learned that Maisie Lockwood’s adoptive parents—Owen Grady and Claire Dearing, both of whom had worked at Jurassic World—were in hot pursuit. The two were inbound for Biosyn Valley on board the Midnight Oiler, the Flying Boxcar piloted by Santos’s smuggler Kayla Watts. Dodgson ordered control room technician Denise Roberts to deactivate the Midnight Oiler‘s ADS beacon, and a pterosaur strike downed the plane. It crashed in the reservoir behind the hydroelectric dam. Not long after this, Maisie escaped confinement in the lab and freed Beta; while trying to track the escapees, Biosyn’s security chief Jeffrey missed Ellie Sattler breaking into the arthropod laboratory and obtaining a sample which would prove Biosyn’s complicity in the locust plague affecting North America. By the time security staff found footage demonstrating the conspiracy, Sattler and Grant were already outbound on the hyperloop, with Maisie in tow.

Those aboard the Midnight Oiler survived the crash and trekked across the valley, avoiding dangerous wildlife as they sought each other out. Dearing had been separated from the others when she parachuted out of the airplane before the crash. The three reunited by nightfall. Meanwhile, Dodgson shut down the hyperloop pod containing Grant, Sattler, and Maisie, causing it to stop at the amber mines station. Dodgson was well aware that there were now Dimetrodons living in the mines and hoped that the spies would fall prey to the animals. He also fired Malcolm, who was then secretly helped by Cole (who had thus far avoided suspicion) to escape and rescue the others from the mines. During these events, the two groups in the valley encountered one another and joined forces.

Dodgson attempted to cover up his complicity in the locust plague by destroying evidence, deleting research files related to Hexapod Allies and incinerating the live specimens. However, a containment failure allowed the captive swarm to escape, releasing many thousands of genetically-modified locusts into the valley; they had already been on fire when they broke free and were now panicked, actively burning and falling out of the sky. This set numerous wildfires around headquarters and much of the northern half of the valley. As per Biosyn security protocols, the animals were remotely herded into emergency containment via their neural interfaces, bringing all of the de-extinct life northeastward. The animals were brought through the research facility’s courtyard and into a bunker beneath the mountain. Biosyn staff members were also evacuated to secure shelters.

The stranded group in the valley made their way to headquarters using the hyperloop tunnel, which was inactive at the time; the fire had grown to the point where it overloaded the facility’s power grid, causing the primary system to seize control of the remaining power and shut down everything it deemed non-essential. From headquarters, the group was joined by Ramsay Cole, who had revealed his role in the incident to Dodgson and left his CEO to fend for himself. Dodgson had boarded a still-active hyperloop pod and made for the airfield to escape. Cole helped the others shut down the primary system and collect Beta. Now that the primary system was offline, they could reroute power to the ADS and safely use a helicopter to escape. When the power was cut, Dodgson’s hyperloop pod stalled; as he sought another way out he encountered a small group of Dilophosaurus that had been unintentionally let into the tunnels during the evacuation, and the theropods killed and ate him.

During the evacuation, the group of survivors including Ramsay Cole also found Henry Wu and allowed him to join as well, permitting him a chance to finish his research and end the locust plague. As the dinosaurs were being evacuated, the old tyrannosaur encountered the Giganotosaurus again and was nearly killed; she survived thanks to the coincidental involvement of the human evacuees, as well as a female Therizinosaurus which fatally wounded the larger carnivore. The survivors were flown by Watts on a Biosyn helicopter out of the valley and to the airfield. There, the authorities arrived by morning to tend to the survivors’ injuries and hear their testimony.

Ultimately, Biosyn was found to have extensive corruption in its executive ranks, which Cole and Malcolm described in detail. Dodgson had died during the evacuation, but many of his subordinates were found guilty and charged with a variety of crimes. Henry Wu was able to finish his research, and while he would still face consequences for his bioethical misconduct, he was able to mitigate the damage his latest project had caused.

Biosyn Valley was not shut down, and remains in operation. The United Nations declared it a global sanctuary, allowing it to carry on accepting troubled animals from around the world. While Biosyn’s facility remains in place, the company no longer has exclusive access to the valley and the scientific discoveries made here are shared with the world. The game Jurassic World: Evolution 2 provides one possibility for what may have happened to Biosyn Valley since the incident, depicting Ramsay Cole taking charge at Biosyn after the purge of Dodgson’s loyalists and taking on Drs. Sattler and Grant as consultants. The dinosaurs have returned to their homes, and the forest will recover from the wildfire. Biosyn Valley continues to serve as a haven for animals that cannot adapt to the modern world and as a site of life-saving biomedical research, both vital roles as the world outside changes ever faster.

Cultural Significance

At the moment there is minimal evidence that humans inhabited Biosyn Valley prior to its being owned by Biosyn Genetics. The hydroelectric dam may predate the company’s presence there, and some people likely lived in the valley when it was being mined for amber in the 1990s.

When it was first announced as a de-extinct animal sanctuary, Biosyn Valley was viewed as a kind of salvation to many governments which had been struggling to determine what action to take regarding the presence of de-extinct life in the modern world. After InGen animals were smuggled off of Isla Nublar, site of the defunct Jurassic World theme park, dinosaurs and other creatures had entered the black market and been released into the wild at different places around the world. Political pressure was mounting to do something, but the technological landscape surrounding genetic science was changing too rapidly for the sluggish pace of legislature to keep up. Biosyn Genetics demonstrated that corporate action was faster than governmental action, and the world’s leaders happily stepped aside to allow the private sector to deal with its problem.

Much of the public had generally positive views of Biosyn prior to the 2022 incident, since Biosyn was removing problem dinosaurs and safely housing them where they would be separated from people, much like they were before Jurassic World’s closure and the subsequent black market boom. The main complaints were that Biosyn was profiteering off of a crisis, since their stock market price would rise after each resolved dinosaur incident. However, much of what Biosyn was telling the public about its sanctuary was actually true. The dinosaurs were indeed being brought there safely, and were permitted to live as they would in the wild. They could feed on what they chose, set up territories as suited them, and if they fought with one another, Biosyn did not control them to make them stop. With no humans in the valley, the dinosaurs were largely free of interference. It was also true that Biosyn was researching the animals in the hopes of discovering new biopharmaceuticals, which were predicted to yield new treatments for all manner of diseases.

Since the valley was mostly a footnote in Italian history before it was acquired by Biosyn, the cultural significance of Biosyn Valley is inextricable from the significance of Biosyn Genetics and its sanctuary. Those who saw the valley as a positive pointed to its effectiveness as a sanctuary, the quality of life the animals could achieve, and the valuable research coming out of it. Those who criticized it typically took a cynical view of Biosyn’s objectives and motives, but not any more so than they would any large corporation. There was relatively little claim of anything truly underhanded beyond Biosyn’s taking advantage of a bad situation for money. During this period of time, Biosyn Valley saw its first truly long-term inhabitants in the form of Biosyn’s employees, many of whom lived on-site in headquarters. They spent their days in the laboratories, or out in the field research outposts, or performing maintenance on the infrastructure. Working at Biosyn was widely considered rewarding; the company provided top-of-the-line pay and benefits, as well as regular raises and promotions which far exceeded those of its competitors. Life in Biosyn Valley was such high quality for everyone who worked there that few people ever questioned when something strange happened.

Behind the scenes, as is now well known, there was much going on that the ordinary employees knew nothing about. There were a handful of incidents involving animals, including an engineer who went missing while working on an area where the hyperloop tunnels intersected the amber mines. There was speculation that an animal had gotten into the mines, despite that area being gated off, and killed him; his remains were later found in 2022, confirming these suspicions. On a larger scale, Biosyn’s secretive Hexapod Allies program was unwittingly responsible for unleashing a locust plague onto North America, one of a size not seen in generations. These were no natural insects, but a new breed created by Biosyn using gene-splicing and de-extinction techniques which InGen had pioneered. Efforts to reestablish control over the swarm without alerting the public to Biosyn’s complicity were underway in 2022, but not going well.

Eventually, these efforts led to exposure of widespread corruption in the company’s executive ranks. Lewis Dodgson, then the CEO of Biosyn Genetics, authorized the kidnapping of Maisie Lockwood in order to provide Henry Wu, a geneticist and wanted criminal, with a research subject to eliminate the swarms quickly and efficiently. Dodgson learned that outsiders had stolen evidence of his crime and were on their way to the press, so in a desperate attempt to stop the news from leaking, he attempted to murder the spies and burn the locusts held in an off-limits research lab. The insects breached containment when lit on fire, causing damage to the valley, its infrastructure, and its animals. All of this, and Dodgson’s knowing complicity in the plague, was relayed to the press by a team consisting of whistleblower Ramsay Cole and scientists Drs. Ian Malcolm, Ellie Sattler, and Alan Grant. Dodgson died during the incident while trying to flee the impending investigation, and those loyal to him were fired and arrested. Biosyn’s name was tarnished in the public eye.

Despite this disaster, Biosyn Valley itself is still viewed in a mostly positive light. Biosyn is under new management, and the valley’s sanctuary still accepts troubled animals from around the world. It is no longer exclusively controlled by Biosyn; the United Nations has stepped in to act as a supervisor, discouraging future corruption and ensuring that bioethical guidelines are established and followed. Life has only improved for the dinosaurs, and with the infrastructure repaired and operational, those employees who were not a part of Hexapod Allies or complicit in covering it up can remain working there under the watchful eyes of international authorities.

Ecological Significance

Since its formation, Biosyn Valley has had a very limited human presence, owing to how inaccessible it is. This means that, while virtually all of Italy’s arable land has been used for agriculture in the thousands of years humans have lived here, this particular area remained a sanctuary for wildlife. Most of Biosyn Valley is dominated by European larch, a type of conifer found commonly throughout the Alps; these trees are frequently festooned with flowery lichen (Usnea florida), a kind of fruticose lichen which grows like beards from the bark and twigs. This lichen is endangered in several European countries, making Biosyn Valley a precious refuge for it. A major threat to the lichen is air pollution, as it is very vulnerable to sulfur dioxide and other industrial byproducts; the climatic isolation of Biosyn Valley protects it. The abundance of flowery lichen in the valley is a testament to how pure the air is. Many kinds of birds thrive in the forests here, with the lichen providing a nesting material while the seeds of the larch trees are an important food source for songbirds and grouse. Cones and needles of the European larch are an important food source for caterpillars. The berries of midland hawthorn plants, which are abundant here, are another food source for herbivorous animals, as are the fronds of lady ferns. In particular, lady ferns are often fed upon by moth caterpillars.

At the moment fairly little is conclusively known about what species of animals naturally inhabit Biosyn Valley, though it is assumed to be similar to the life of the neighboring valleys. Bird and insect sounds, including flies, can be heard in the forests, and there are probably fish and various invertebrates living in the rivers and lakes. Wetlands are a potential breeding ground for amphibians, which would do well in the comparatively warm and humid climate of the lowlands. Higher into the mountains there are fewer plants and animals, and in terms of vertebrate life there may just be mainly the hardier species of birds and mammals. Throughout the Dolomites are various kinds of antelope and deer, as well as birds such as buzzards and eagles, which may live in the mountains surrounding Biosyn Valley. Central European red deer are known from nearby areas, but currently cannot maintain a breeding population within Biosyn Valley itself as they are preyed upon too heavily by de-extinct megafauna. The valley’s current owners import deer from elsewhere in Italy to sustain a population. Less still is known about the caves beneath the mountains, which contain plenty of water and may provide home to subterranean fauna. It has been suggested that bats could roost in the caves at night, but none have been seen there, nor evidence of their presence such as guano. It is more likely that bats live in the trees outside. Eleven species of bats are known from the province of Belluno and four from Pordenone; any of these bats could potentially live in Biosyn Valley, which is on the border of these provinces.

Although the animals of Biosyn Valley lived mostly without human intervention, the valley’s isolation sparing it from the land becoming developed or polluted, this has now changed. The Italian government had sold the land to Biosyn Genetics in the 1990s for amber mining, but the mines were abandoned when plans did not pan out as expected. For decades it sat unused by human interests until the later 2010s. At that point, Biosyn began building infrastructure, including its enormous new headquarters and a colossal hydroelectric dam, one of the biggest in Italy (though the dam may have existed prior to Biosyn purchasing the land). The dam reduced water flow into the valley, and with headquarters built over the other river tributary, this also impacted the valley. Biosyn’s plan for this new facility was to create a de-extinct animal sanctuary which would receive dinosaurs and other de-extinct creatures from around the world, as well as provide a research facility that Biosyn could use to study and create its own animals. By the 2020s, many species had been shipped to the valley, putting pressure on its native species.

Biosyn did, however, try to let nature take its course once the dinosaurs were introduced. They would add new animals as time went on, but they did not built extensive infrastructure; access roads were even disused in favor of underground tunnels, though the caves were used for construction of these and therefore some life forms were still impacted. However, it reduced air pollution in the valley that would have resulted from vehicle emissions. Red deer cannot maintain a population due to introduced predators, but deer are imported from nearby areas. The plant population seems to still be flourishing, with abundant flowery lichen demonstrating the air quality is exceptional. Biosyn was responsible for one major ecological disaster which threatened not only modern animals but also harmed the introduced de-extinct species. In early 2022, an effort by Biosyn’s CEO Lewis Dodgson to cover up corporate corruption ended up causing a massive wildfire, which damaged much of the northeastern valley and scattered areas to the south. The fire was short-lived, being extinguished by rainfall after a few hours, but many acres of forest were burned. Stages of ecological succession are now taking back the burned areas.

De-extinct animal species housed here include some which were originally bred by Biosyn’s competitor, International Genetic Technologies, as well as some which were originally bred by Biosyn itself. Others were created by third parties, including non-corporate creators. During Biosyn’s ownership of the valley, it housed 20 animal species imported from cooperating governments in addition to Biosyn’s homegrown species. As of mid-2022, there were 50 animal species total inhabiting the valley. Currently confirmed species include:

- Allosaurus jimmadseni – initially bred by InGen

- Ankylosaurus magniventris – initially bred by InGen

- Apatosaurus ajax – initially bred by InGen

- Baryonyx walkeri – initially bred by InGen

- Brachiosaurus altithorax – initially bred by InGen

- Carnotaurus sastrei – initially bred by InGen

- Compsognathus longipes – initially bred by InGen

- Dilophosaurus “venenifer” – initially bred by InGen

- Dimetrodon grandis – believed to be a Biosyn exclusive; some sources suggest it was previously bred by InGen

- Dimorphodon macronyx – initially bred by InGen

- Dreadnoughtus schrani – DNA acquired by InGen, initial breeding by Biosyn

- Gallimimus bullatus – initially bred by InGen

- Giganotosaurus “ultimus” – DNA possibly acquired by InGen, initially bred by Biosyn (likely extinct as of 2022)

- Iguanodon bernissartensis – assets possibly bred by InGen, Biosyn, or both independently

- Lystrosaurus curvatus – unknown; possibly initially bred by Biosyn

- Microceratus gobiensis – initially bred by InGen

- Moros intrepidus – initially bred by Biosyn

- Nasutoceratops titusi – initially bred by InGen

- Orthoptera hybrid – genetically engineered by Biosyn (likely extinct as of 2022)

- Parasaurolophus walkeri – initially bred by InGen, new variants bred by unknown parties

- Pteranodon longiceps – initially bred by InGen

- Pyroraptor olympius – initially bred by Biosyn

- Quetzalcoatlus northropi – most likely initially bred by Biosyn

- Sinoceratops zhuchengensis – initially bred by InGen

- Stegosaurus stenops – initially bred by InGen

- Stygimoloch spinifer – initially bred by InGen

- Therizinosaurus cheloniformis – DNA acquired by InGen, initially bred by Biosyn

- Triceratops horridus – initially bred by InGen

- Tyrannosaurus rex – initially bred by InGen

- Velociraptor “antirrhopus” – initially bred by InGen

This is only a partial list of species found in the valley. There is no evidence at the moment of de-extinct plants growing here; since the cultivation of de-extinct plants is limited in scale compared to the illegal breeding of de-extinct animals, they are not an immediate issue at the moment, but this may change in the future. As the political and ecological situation surrounding de-extinction and Biosyn Valley shifts, the list of species housed here is likely to change too.

The precise ranges of many of these animals is not completely known, but the five major ecosystems in Biosyn Valley are all home to distinct species. Forested areas are inhabited by many of the herbivores, such as Parasaurolophus, Brachiosaurus, Triceratops, and Iguanodon, which feed on the plant life. The major predators in the forest are Tyrannosaurus and Dilophosaurus; prior to the death of the only known specimen, Giganotosaurus was also dominant in this ecosystem. The small scavenger Moros was commonly seen near the Giganotosaurus. Sources of fresh water are visited by all the animals, but some in particular favor wet areas; Nasutoceratops and Dreadnoughtus are often seen here, with the latter bathing in lakes around midday. The pterosaur Pteranodon is usually seen around Dreadnoughtus, perching on its back. They likely feed on fish that gather around their gigantic host. Wetlands are often visited by the predator species, but are also home to the herbivorous Therizinosaurus. Fewer species live in the mountains, but this is known to be home to nomadic Pyroraptors, which dive for food in the alpine rivers away from their competitors. The caves, like the high altitudes, have fewer inhabitants, but Dimetrodons nest in these sheltered spaces, lounging in subterranean ponds and caching food that they capture outside. Above all these ecosystems, the gigantic Quetzalcoatlus rules the skies, descending upon whichever region of the valley it chooses. While the large theropods are usually viewed as the apex predators, this huge pterosaur is their equal in terms of dominance in the food web.

Behind the Scenes

Based on some early promotional material and leaked earlier scripts, Biosyn Valley was originally planned to be located in the Caucasus Mountains rather than the Dolomites. The reason for the change is unknown. This earlier concept is still reflected in some material, such as the board game released with Jurassic World: Dominion, which depicts the sanctuary in southwestern Russia rather than northern Italy.

The Dinotracker website gives coordinates for Biosyn Valley which place it at the mountain Cimon del Froppa. In real life, the area which Biosyn Valley occupies is home to the Piave Valley, which actually does have an enormous dam, but it is not in use due to being the site of a disaster which claimed thousands of lives. Presumably the Piave Valley still exists in the film universe, as it appears on the Dinotracker map in place of Biosyn Valley, but these two valleys are not the same.