Compsognathus, also called the “compy,” is a genus of small theropod dinosaur in the family Compsognathidae which grows to roughly the size of modern-day turkeys. This animal lived in what is now Europe, with specimens being recovered from Germany, France, and possibly Portugal; between 156 and 145 million years ago, during the Tithonian age of the Jurassic period, these areas would have been tropical archipelagos. Its genus name means “delicate jaw;” there is only one species, C. longipes, with a specific epithet meaning “long foot.” Despite its small size, it is believed to have been the top predator in its habitat simply due to the fact that no large animals have ever been discovered there.

Compsognathus, also called the “compy,” is a genus of small theropod dinosaur in the family Compsognathidae which grows to roughly the size of modern-day turkeys. This animal lived in what is now Europe, with specimens being recovered from Germany, France, and possibly Portugal; between 156 and 145 million years ago, during the Tithonian age of the Jurassic period, these areas would have been tropical archipelagos. Its genus name means “delicate jaw;” there is only one species, C. longipes, with a specific epithet meaning “long foot.” Despite its small size, it is believed to have been the top predator in its habitat simply due to the fact that no large animals have ever been discovered there.

The first known fossil of Compsognathus was discovered in Bavaria, Germany in the Solnhofen limestone formations by fossil collector Joseph Oberndorfer. These limestone quarries were already known for excellently-preserved specimens of fish, pterosaurs, and small dinosaurs such as Archaeopteryx. The species was named by Johann A. Wagner in 1859, the same year it was discovered. Compsognathus was instrumental in forwarding the idea that birds are a type of dinosaur, based on the similarity between Archaeopteryx and Compsognathus.

This first specimen measured 35 inches (89 centimeters) in length, making it the smallest known nonavian dinosaur at the time of its discovery. Over a century later in 1971, a larger specimen was discovered in the Canjuers plateau near Nice, France; this skeleton measured 49 inches (125 centimeters) long. Originally, the French specimen was classified as C. corallestris, but it was eventually identified as the same species as the German specimen by various scientists in the ensuing years.

There is only one recognized species of Compsognathus today. It is sometimes confused with the earlier small theropod Procompsognathus triassicus; most modern scientists disagree with the earlier theory that there was an evolutionary relationship between the two animals. Paleontologist Dr. Robert Burke has confused the two species, referring to C. longipes as C. “triassicus,” a name which is nonsensical as Compsognathus had not yet evolved during the Triassic period. He also identified it as having been discovered “by Fraas in Bavaria in 1913,” a description that is applicable to Procompsognathus. Jurassic-Pedia has opted to use the incorrect taxonomy for unknown reasons.

Compsognathus longipes was one of the theropods cloned by International Genetic Technologies in the 1980s and 1990s. This was accomplished using ancient DNA preserved in amber inclusions dated to the Jurassic period within hematophagous invertebrates such as mosquitoes. While it was not successfully exhibited in a de-extinction theme park, its adaptability has made it one of the most prolific of the animals created by InGen. It readily establishes itself in new environments without human assistance, making it one of the few de-extinct vertebrates with real potential to become an invasive species.

As of June 11, 1993, InGen had created up to Version 2.050 of this species.

Description

Among the smaller dinosaurs, Compsognathus reaches an average length of four feet (1.2 meters). InGen’s specimens rarely reach these dimensions, remaining closer to the juvenile proportions and scarcely growing larger than a chicken; it may be found weighing only 0.44 pounds (0.2 kilograms). Fossil evidence suggests that, when at its full size, Compsognathus would weigh between 1.8 and 7.7 pounds (0.83 and 3.5 kilograms). However, some sources suggest that the biggest of InGen’s specimens could reach a height of 1.6 feet (50.8 centimeters) and a length of five feet (1.5 meters), weighing up to eleven pounds (about five kilograms). This would mean that, while most of InGen’s compies are smaller than their fossil relatives, they have the potential to grow larger than known fossils provided they are not eaten by predators first.

These quick, nimble creatures are skinny and lightweight, with much of their length consisting of the thin tail and dainty neck. The skull appears delicate, but is actually armed with a strong jaw and dozens of small, needle-sharp teeth. In the front of the jaw, the teeth are smoother and lack serrations, while the teeth in the rest of the jaw are flattened from side to side. The large eyes are equipped with equally large pupils, which are round like those of a diurnal bird, and dark brown sclerae. These allow it to make precise movements with its neck and head, quickly striking to nip at a piece of food and then pulling back. Overall, its skull is narrow with a tapering shape. There are venom glands in the mouths of some, but not all, compy lineages.

Its body usually appears scrawny, though this depends on the environment; when well-fed, such as in an environment with readily-available carrion, slightly plumper Compsognathus can be seen. Their narrow frame is essential for their survival, though, since they rely on speed and agility to capture food and avoid predators. Compsognathus is aided in this endeavor by its long tail, which is useful for balancing while running, and by its long legs and feet. The three toes end in small claws. A fourth toe, called the hallux, is vestigial; it completely lacks a claw in some populations.

The front limbs are much smaller than the hind limbs, but are still functional and can be used to grasp prey. Paleontologists are still unsure as to whether Compsognathus naturally has two or three functional fingers; the general belief for many years was that only two of the digits possessed claws, and that the third finger was vestigial. Some scientists disagree, however, suggesting that the third finger was still more developed. InGen’s specimens do only have two functional fingers, each of which ends in a small claw; as with all of their theropods, the hands of Compsognathus are capable of pronation, which its fossil ancestors’ were not. The third finger is reduced in size, and is entirely absent in some populations.

In more recently-developed populations, the vestigial digits of Compsognathus have become slightly more prominent. Animals seen between 1993 and 2001 were typically found to lack the third finger and fourth toe, while those found in more recent years can be seen to have them. Whether this can be attributed to genetic engineering or naturally-occurring genetic drift is presently unknown.

Many relatives of Compsognathus were covered in down-like feathers, but at least InGen’s specimens lack this integument and are instead covered in smooth scaly skin. Paleogeneticist Dr. Laura Sorkin suggested that genetic engineering may have unintentionally removed feathers that would naturally have grown on Compsognathus (as was later determined to be the case in Velociraptor and other theropods); however, some fossil evidence suggests that not all compsognathids were feathered, and that Compsognathus itself may have indeed been scaly on at least part of its body in prehistory as well.

To help it survive in its environment, compies are colored for camouflage with variable green coloration ranging from a dusky evergreen to a more vibrant yellow-green; rare reddish-colored compies are also known. Nearly all have vertical stripes, typically a fairly dark blue or green but sometimes gray, which help them to blend in with tall grasses and other plants. These stripes are present on the back, neck, and tail of most specimens, and are accompanied by horizontal stripes of the same color on the legs of some. It exhibits countershading, with the underside appearing a lighter color than its back. Under its neck, it has a dewlap, which is reddish in the male and likely functions as a display structure. During most times of the year, this dewlap is reduced in size and faded in color, becoming more pronounced with seasonal changes. At least one melanistic compy, with black coloration, has been seen.

In more recent years, brown-colored Compsognathus have been reported to the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife in drier regions. It has been hypothesized that these less colorful compies are adapted to new habitats where there is less greenery, making it necessary for them to camouflage against rocks and substrate.

Growth

Thus far no hatchling or juvenile Compsognathus have been observed, but InGen’s specimens are similar in proportion to the juveniles and subadults seen in the fossil record.

Hatchlings can be created in the mobile game Jurassic Park: Builder, appearing proportionally similar to the adults.

Sexual Dimorphism

Though subtle, sexual dimorphism is present in Compsognathus. Males are a darker, more vibrant shade than females, which have a more faded color. However, individualism can obscure this, as some are lighter or darker than average, and some show colors other than green. It can be difficult to sex an individual compy without a visual comparison. The male’s dewlap is enlarged and red during courtship, though some prominently-dewlapped animals have also been described (albeit by laypeople who likely would not know any better) as females.

Habitat

Preferred Habitat

The compy is an adaptable creature, capable of acclimating to a variety of habitat types. Its coloration makes it best suited to grasslands and bushes, where its green scales and distinct stripes help it blend in with its surroundings to avoid predators. However, it also flourishes in forests, particularly those with thick undergrowth or large organic debris. Compies have been known to inhabit semi-arid regions, marine coastal areas, and wetland, all with a good degree of success. They have even been seen in developed areas and farmland. Its prehistoric habitat is believed to have been dry but tropical archipelagos surrounded by flourishing coral reefs. Despite the warm tropical environment that it originally lived in, it can adapt just about anywhere, tolerating a wide range of temperatures thanks to its active warm-blooded metabolism.

Compies will shelter from larger predators in underground runs and warrens, which they usually build from preexisting tunnels among the roots of trees or human infrastructure. These can become quite extensive, and are often marked with the remains of prey such as small mammals, birds, and reptiles. Bones are often scattered around compy warrens.

Muertes Archipelago

InGen bred Compsognathus at the Site B facilities on Isla Sorna sometime between 1986 and 1993, though the exact date is not known. As of last headcount in 1993, there were forty-eight compies living on Isla Sorna. Their habitat could have ranged anywhere on the island; populations were later found to have established all across it. Due to their rapid breeding rate and ability to adapt to new environments readily, they are probably found on other islands of the Muertes Archipelago; however, no studies have gone into detecting populations there.

In mid-December of 1996, a group of 21 adults was encountered on Isla Sorna’s northern coastline. The species was also sighted farther from shore in May 1997; between six and nine adults were found near the northeastern game trail, while a group of twenty-nine were seen in a wooded area north of the Workers’ Village. Of the game trail population, between two and eight were captured by the InGen Harvester operation. When the camp was sabotaged and destroyed, two caged individuals were not released and were directly in the path of a Triceratops attack. Six animals were seen fleeing the camp; it is unknown if the two seen in cages were among them. If the caged two did not escape, and managed to avoid being crushed in the attack, they probably starved. It is unknown if the six animals seen fleeing had been captured beforehand, or if they were simply lingering near the camp.

All of these were mixed-sex groups, though the sex ratios are unknown. There appear to have been similar numbers of males and females. Behaviors in the compy flock seen north of the Workers’ Village imply that they may have been the same flock encountered near the game trail; however, the flock on the northern coast is most likely a separate and distinct population. Between 1996 and 1997, there were at least fifty compies on the island. If the two seen in cages during the 1997 incident were not released, then there were at least fifty-two, and if the population in the central island was distinct from that of the game trail, there could have been as many as sixty-one compies on Isla Sorna at the time of the 1997 incident. Of course, it is likely that others remained unseen.

In 2001, more compies were encountered in the island’s western region. During Eric Kirby‘s time marooned on the island during the late spring and summer, he reported a flock of compies living near the western coastline as of May, though exact numbers were not given. On July 18, four compies were briefly spotted near the Site B Airfield, but were evicted from their nests by a conflict between two much larger theropods. During the evening of that day, a flock of at least eight were seen near the remains of a water tanker truck that Eric Kirby had used as a makeshift shelter.

The Jurassic Park Adventures junior novel series, particularly the second book Prey, describes a large flock of compies living near Mount Hood in the island’s southwestern region as of the very end of December 2001. The exact population numbers for Isla Sorna’s western regions are not known, but assumed to be comparable to the eastern island’s population. Only twelve animals have been specifically headcounted, but language used to describe compy groups in the west generally imply a large population size.

Without a doubt, Compsognathus was the most numerous de-extinct carnivore on Isla Sorna between 1993 and 2004. During the chaotic final years of Isla Sorna’s artificial ecosystem, compies would have been among the few creatures to really benefit; as the ecosystem collapsed due to overpopulation, the carcasses piling up would have fed the compies well. Even so, their numbers probably decreased dramatically after late 2004, when Masrani Global Corporation took the initiative to move animals to Isla Nublar for their own safety (and to stock Jurassic World). It is unknown how many compies were successfully relocated. According to Masrani Global and other authorities, there are no dinosaurs left on Isla Sorna; however, the island is still restricted for unknown reasons. Additionally, the small size and cryptic coloration of the Compsognathus would make it very hard to track down and capture every single one, and they have already established an ability to evade human containment measures and establish themselves in an ecosystem. This makes them the likeliest candidates to have survived the collapse and purge of Isla Sorna. Even if the island is truly emptied of de-extinct life, compies may still live there undetected.

Jurassic Park: San Diego

InGen had plans to eventually exhibit Compsognathus in their Jurassic Park facility located in San Diego, California. These plans were changed in the 1980s as then-CEO John Hammond opted to abandon Jurassic Park: San Diego and instead construct on the exotic tropical island of Isla Nublar, so no compies were transported to the United States at that time. When InGen briefly attempted revival of the original Park locale in 1997, compies were again among the species planned to be put on exhibit, with several adults being captured. However, none were successfully transported off the island, and so Jurassic Park: San Diego did not see this species put on display.

Isla Nublar

As of June 1993, plans were in place to eventually house Compsognathus in a paddock in Jurassic Park in the central or southern part of Isla Nublar. However, this paddock was not yet constructed, and that area was occupied by other animal paddocks at the time.

Supposedly, no compies were present on Isla Nublar in 1993 at all. However, this assumption was proven incorrect during the 1993 incident and 1994 cleanup operation. A total of seventeen were spotted at the abandoned Visitors’ Centre during the evening of June 12, while more were sighted in the forest to the north of there. A further seven were sighted at the Western Ridge, while two more were seen in the northern forests near Dr. Sorkin’s laboratory. Seven animals may have been present in the area slightly later. In fact, Dr. Sorkin’s personal journal details her studies of Compsognathus, suggesting that she knew they were on the island already. Other staff members, including chief veterinarian Dr. Gerry Harding, were also unsurprised to see these animals on Isla Nublar. This suggests that, while they were not supposed to be on the island yet, their existence was known to much of the staff.

All together, there may have been as many as thirty-three adult compies on Isla Nublar by June 12, 1993; however, it is also possible that some of them were simply seen more than once, and equally possible that there were others on the island not seen at all. The 1994 cleanup operation counted twenty-eight animals as of October 5, stating that they had probably stowed away on cargo ships from Site B. If this is the case, they probably entered Isla Nublar via the East Dock.

The population persisted on the island for years after it was abandoned in 1993, easily becoming the most numerous de-extinct species. Isla Nublar provided them with a habitat in which to flourish, and they were still quite common when the island was recaptured by InGen in 2002. For the safety of park workers, the compies were confined to certain reaches of the island.

As of 2004, the compies were considered to be free-roaming over most of the island, since their small size and unknown number made them more difficult to contain than other dinosaurs. From late 2004 to early 2005, their population likely increased with specimens from nearby Isla Sorna being introduced to the island. After some time in the quarantine paddock, they would have been integrated into habitats in Sector 5. There is currently no evidence that they were successfully put on exhibit in Jurassic World, but they were maintained in a small pen near the Camp Cretaceous site as of late 2015. Escapes were more common than other species, but not a major safety concern as compies are not especially dangerous. For example, an adult female escaped the pen on December 19, 2015 and encountered campers bound for Camp Cretaceous, but was easily captured by camp counselors using a blanket and a cat carrier and delivered to the Jurassic World Park Rangers for recontainment.

During the incident in 2015 which closed Jurassic World, multiple compies escaped containment as rangers and other security staff focused their efforts elsewhere. Three escaped adults were sighted on the road between the River Adventure and Jurassic World Lagoon during the day, and that night a group of fifteen were seen in a maintenance tunnel leading from the Golf Course to Ferry Landing. The following day, one male and three females were seen in the remains of a damaged gyrosphere just north of the valley, and a further thirty (including eighteen males and twelve females) were seen on Main Street nesting in the buildings. In March 2016, a group of four including two males and two females was spotted at the Camp Cretaceous site. Five to seven more were sighted at a watering hole nearby, and the following day, five were sighted near an illegal campsite some distance from Camp Cretaceous. Finally, the day after this, a pair of females was seen in the Ferry Landing harbor building, using the maintenance tunnels and damaged infrastructure to navigate around. These are the southernmost confirmed compies on the island.

By 2016, the compies had bred, with one nesting site confirmed in the derelict Jurassic Park Visitors’ Centre in June. Between March and June, they vacated more exposed nesting grounds such as Camp Cretaceous due to the activity of the Scorpios rex. There were at least eleven compies living here and constructing nests in the ruins. Their range extended to the private pier near the Kon penthouse. One compy was killed and eaten by a Velociraptor that June, and not long afterward the Centre suffered extreme structural damage that probably made nesting there impossible. Two or three were living in the field genetics lab at around the same time. One male was accidentally removed from the island in June when it unwittingly stowed away on a damaged yacht.

The population survived well into 2018, adapting to changes in the environment after the park was abandoned. Artificial barriers were lifted around much of the island, permitting animals to roam as they chose. At least three, and probably five or more, were confirmed living in the North Mount Sibo Genetics Centre on February 17, 2018, including at least one female and two males. Some Compsognathus were recorded living near the aviary ruins, while one adult was sighted at Main Street on June 23, 2018. Many compies, however, remained in forested areas and grasslands to the island’s north. On June 23, 2018, four were sighted near a small creek to the south of Mount Sibo, while three more were sighted southwest of the mountain. A further sixteen were seen on the volcano’s eastern flank; these compies were driven eastward when the volcano erupted, and were forced to scatter to avoid a stampede of much larger animals.

In addition, at least eight adult compies were removed from the island by means of the S.S. Arcadia under the direction of Ken Wheatley. The last one to be logged into the ship’s manifest was measured to weigh three kilograms, or 6.6 pounds; it was kept in Container #31-1022-2647 (Cargo #24573) and cosigned into the manifest by Jon Brand at 14:01. It was highlighted in green in the manifest, likely indicating good health.

All together, this means that there were at least thirty-two adult compies on the island at the time of the 2018 eruption of Mount Sibo. With around thirty-three on the island in 1993, twenty-eight confirmed in 1994, and at least thirty-eight in 2015, the compy population on Isla Nublar was among the most stable over the course of these twenty-five years. Some compies seen in more recent years have a distinctly different phenotype than those seen during the 1990s and early 2000s, suggesting that they are not the same animals.

The eruption of Mount Sibo has negatively impacted the compies. After feasting on the initial carnage, the compies’ food sources would have depleted. Without plant life, the insects and other invertebrates would have decreased in number, causing a trophic collapse impacting all levels of the food chain. Herbivorous animals would have died out, followed by the carnivores. Even the freshwater fish were largely killed off by toxic algal blooms and volcanic outgassing throughout 2018, depriving the compies of another food source. Ultimately, while some may have managed to eke out a living feeding on marine detritus and whatever small animals they can find since the eruption, most of the food that helped them flourish is now gone. As of 2022, Mount Sibo’s activity has subsided and plants have begun to grow back, so any surviving compies may be able to recover. In fact, with the larger carnivores driven to extinction, compies may be more dominant predators on the island now.

Mantah Corp Island

Although InGen’s rival Mantah Corporation succeeded at stealing several species of de-extinct animal before Jurassic World’s closure in 2015, Compsognathus was not among them. This was not due to difficulty in obtaining one, but rather the fact that Mantah Corp’s President intended their facility on Mantah Corp Island to be used for pit fighting for entertainment and Compsognathus were simply too small to be appealing.

Despite the lack of interest, a single adult male compy was accidentally introduced to the facility in June 2016. It arrived on a damaged yacht which wrecked on the island’s coast, having stowed away from Isla Nublar. The animal entered the facility’s desert biome via a natural cave, traversed through the maintenance tunnels, and was finally apprehended in the forest biome where the facility’s automated security system terminated it.

Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary

After being released into the wild in 2018, this species boomed around the world due to both natural and captive breeding. The governments of several countries authorized Biosyn Genetics to capture de-extinct animals, including Compsognathus, and securely contain them. Twelve compies were transported to the Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary by Kayla Watts in February 2021.

As adaptable creatures, compies could live in most parts of the valley, but likely stick close to the herds of herbivores that live near the rivers and among the forests. They would provide the compies with food in the form of dung and insects, as well as keep smaller predators at bay. The valley’s forests also make for ideal nesting habitats. Some of the forest cover was lost in the spring of 2022 due to a wildfire accidentally started by Biosyn; during the fire, all the valley’s de-extinct life was herded into the emergency containment area. Once rain had extinguished the fire, the compies and other animals could return to what remained of their habitats. After the incident, the United Nations took over supervision of the valley, reducing Biosyn’s power there. This had little meaning to the compies that already inhabited the valley, but changed protocol for how the operation was handled.

Black market

The small size of this dinosaur makes it easy to smuggle, so it has been targeted by de-extinct animal poachers across the years. Some may have been poached from Isla Sorna and Isla Nublar between 1997 and 2018, though details are scarce. The first confirmed case was in June 2018, at which point mercenary hunter Ken Wheatley was contracted by financier Eli Mills to capture numerous animals from Isla Nublar and transport them via the S.S. Arcadia to the Lockwood estate. There, just south of Orick, California, the animals were illegally put up for auction. At least eight Compsognathus, and possibly more, were intended to be sold. None are believed to have made it to potential buyers, since the auction was disrupted, but a case of DNA samples was sold to a Russian buyer. It is highly suspected this was the mobster Anton Orlov.

Since these dinosaurs’ DNA is now on the black market globally, and the small animals themselves are fairly easy to come by, they are traded under the nose of the law around the world. A major hub for this illegal trade is the Amber Clave night market in Valletta, Malta. In early 2022, a small flock of compies was documented on the market here; due to a disruption the animals were accidentally let loose and fled into the streets of Valletta.

Wild populations

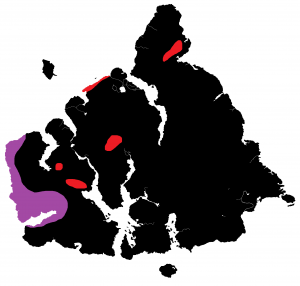

Compsognathus originally evolved about 156 million years ago among the islands of the European Archipelago. At the time, this was a tropical environment with few large terrestrial predators. Compies are believed to have lived on islands that later became France, Germany, and possibly Portugal. After around eleven million years of existence, this species became extinct due to changes in its ecosystem. It remained extinct for 145 million years until genetic engineering brought it back to life in a new form.

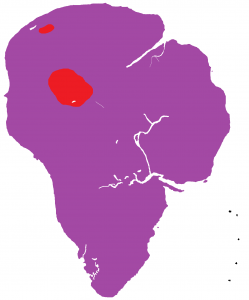

Since 1994, there has been a precedent for compies as an invasive species. They were planned to be exhibited at Jurassic Park: San Diego in 1997, but were not successfully brought off Isla Sorna at that time; despite this, it is possible that they reached the Americas or other parts of the world during the late twentieth century via InGen cargo ships. The InGen IntraNet website, which was last updated in 1997, hints that a population of compies may have established at Toluca Lake in Los Angeles, California, USA. Compies were confirmed in North America as of June 24, 2018 when at least eight adults were transported from Isla Nublar to the Lockwood estate near Orick, California. They were intended to be sold on the black market, but were released from the estate by Maisie Lockwood to prevent them from dying due to hydrogen cyanide poisoning. Since then, they have been reported throughout the western United States, the population apparently booming in the ensuing years.

By 2019, three were captured in Allendale, Washington by the recently-formed Department of Prehistoric Wildlife. As of early 2022, this little dinosaur was reported in the states of Colorado, South Dakota, Iowa, and Missouri. By mid-2022, compy populations had been detected as far north as Salem, Oregon, as a specimen was captured and reported to the DPW. They became known for sneaking into households throughout the country in search of food; on June 11, the DPW advised people to keep compies out of their homes after a person in Cleveland, Ohio reported repeated entrance attempts by compies in the neighborhood. Jurassic World Evolution 2 depicts this species occurring in the wild as far north as the North Cascades of Washington State, though it is uncertain if their presence was due to poachers who had a camp nearby or if they migrated there on their own. Others, more likely having migrated naturally, can be spotted in Yosemite National Park, California. Its northernmost population, which has been tracked by the CIA’s dinosaur tracking division since at least 2021, lives around Lake Athabasca in Canada.

Due to the international black market, and the compies’ proclivity for stowing away on ships, they have appeared around the world. Some escaped the black market in Malta in the early spring of 2022 and were last seen in the streets of Valletta. Their small size and elusiveness means that some may never have been recaptured. Elsewhere in Europe, other compy populations have been reported. A pack of at least three were filmed by a bystander in Rome, Italy during a brief incident in which one of them stole the man’s smartphone. Another pack of five individuals has caused repeated power outages in Petit-Caux, France, and has yet to be safely relocated; others inhabit woodlands in France’s Massif Central. They are known from the Douro River in Spain, and from the Wallachian Plain of southern Romania. A solitary individual was also photographed in Weurt, Netherlands. They are also known from the European Plain from western Russia to eastern Kazhakhstan, the Turpan Depression in northern China, near the confluence of the Chenab and Indus Rivers in Pakistan, and in the hyper-arid Rub’ al Khali of Saudi Arabia.

Five were reported in Brazil (exact location undisclosed) on the night of May 12, 2022. Compies seem to do well in Brazil, being recorded by the CIA’s dinosaur tracking division on the border of the Brazilian Highlands and Amazon Basin. As with many cases, it is impossible to tell whether these animals were smuggled to the area on purpose, or if they stowed away in transport.

Compies have also established in Africa, where they are now a part of the savanna food web. Their range overlaps with that of the cheetah, which preys upon them. The CIA has been tracking a population near the Jur River of South Sudan since at least 2021, and another near Lake Chad.

Finally, compies have been tracked in Australia by the CIA, which has found them living near Lake Woods in the northern part of the country. This is located between the Barkly Tableland and Tanami Desert. In many parts of the world, especially in remote wildernesses, it is highly likely that the compy populations are far higher than reported since they can easily evade detection here.

Behavior and Ecology

Activity Patterns

This theropod is crepuscular, active mostly at dawn and dusk and avoiding the temperature extremes of midday and midnight. It may be seen intermittently throughout the morning and afternoon as well, during which time it hunts and socializes. When they sleep, they huddle together for warmth, safety, and comfort.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Compies are carnivores, feeding on a variety of small animals including reptiles, insects, and amphibians. Some paleontologists such as Dr. Robert Burke have suggested that the compy was exclusively a scavenger, but real paleontological evidence contradicts this assumption. In their native Jurassic period, their diet is known to have included small reptiles, such as the agile lizard Bavarisaurus; in the modern day, compies may take prey that they could not have encountered during prehistory. Small mammals, such as rats and mice, are easily within the range of a compy’s prey animals, as are some of the smaller modern birds. It still feeds on lizards, frogs, and insects. It struggles to bring down prey larger than itself owing to its delicate build, so it usually targets small creatures that cannot fight back. Some compies have mild venom, not enough to kill a human outright, but enough to kill small prey or weaken larger prey.

To kill a prey item, the compy employs its excellent sense of vision to track the prey’s movements before delivering a quick, precise nip with its jaws. It efficiently immobilizes the prey before consuming it whole, or tearing off smaller pieces if the prey is too large to fit in its mouth. It also scavenges from carcasses, ripping pieces of meat from the body of a dead animal. Because it is much smaller than other carnivorous animals in its habitat, the compy must be wary when scavenging; at the first sign of a threatening competitor, it will scurry away. They have been known to dash in and steal dropped pieces of food from larger carnivores, but flee the moment they sense that they may be in danger.

Some compies are known to practice social hunting behavior. To incapacitate a larger prey item, one member of the compy flock will emerge and get the target’s attention. This is a risky move for the compy, as it could easily be killed should a large target turn aggressive. While the target is distracted by the lone compy, the others will move into position and mob the target from all sides, biting and tearing at any exposed flesh to create dozens of small bleeding wounds. If the target fights back too much, they will fall back and wait for it to weaken before moving in again, stalking it if necessary. Eventually, the compies can kill even a human-sized (or slightly larger) prey item if they are patient and careful enough. This behavior probably first developed as a defense mechanism against predators, since in prehistory, the Compsognathus lived on islands without any large predators.

However, the compy is an opportunistic eater, and will take food any way it can. It has been known to eat processed meat products such as roast beef, cooked fish, and jerky, and has been observed scavenging other forms of processed food such as frozen pizza and chocolate. It will also accept commercial cat foods. It is probably an experimental feeder, probing any new potential food to determine whether it is edible. When a compy identifies a food source, its fellows are usually not far behind. They will rapidly swarm any available food, devouring it before any rivals can show up to compete. Despite their frenzied meals, they do not act aggressively toward one another and appear able to share the food among themselves without much infighting. While it has not been observed directly, The Lost World Movieplay book describes these dinosaurs as occasional cannibals.

In addition to consuming all kinds of meat, compies practice coprophagy, or eating the feces of other animals. This is an uncommon behavior among birds and other reptiles, but has been documented in mammals. In compies, coprophagy probably allows them to obtain nutrients that they could not normally get from their diet, such as plant-based nutrients from the dung of herbivores. As a carnivorous animal, the compy does not eat plants, but it could instead consume the dung of herbivorous animals. On a single occasion, one compy was observed trying a variety of berries as food items, even though its usual diet is insects and carrion.

Some evidence exists to suggest that compies may eat eggs. Footprints belonging to this species were found near a Dilophosaurus nest, though there was no damage to the eggs. The parent may have driven off the compies before they could feed. It has also been suggested due to their association with Troodon pectinodon that they may eat the Troodons‘ leftovers, including organic material the larger animals use in nesting. During the 2015-16 incident on Isla Nublar, Darius Bowman confirmed compies eating the eggs of other animals. He also kept a record of their scavenging and feeding behaviors; he confirmed that their diet includes butterflies and moths, insect larvae, flies, centipedes, dragonflies, beetles, other insects, and carrion.

Social Behavior

The compy’s collective hunting technique probably developed from preexisting social behaviors. This is by far the most gregarious theropod cloned by InGen, forming tightly-knit social groups of nearly thirty animals. It is unknown if these are influenced by family relationships or if breeding takes place within the same social group, but in any case, compies are seldom seen far from members of their own kind. Groups of compies are referred to as flocks, packs, or swarms, usually depending on how they are behaving at the time. They will cooperatively build large underground runs from tunnels and crevices that they find, living there to hide from bigger predators and bringing prey items back to eat.

On its own, a compy is certainly capable of surviving, but it really only flourishes in groups. Even a small group of three or four animals gives each individual a better chance of surviving; one member of a flock will alert its fellows to the presence of food or danger using a complex variety of vocalizations and body movements. The compies will swarm over food items and cooperate to mob larger prey, and will scatter if one member spots danger. After they scatter, compies are quick to regroup.

However, the compy is not especially intelligent. Its pack-hunting behavior is often compared to that of theropods such as the Velociraptor, but it is not nearly so complex. Compies engaging in cooperative attacks are not necessarily planning strategy. It is more accurate to describe this as collective mobbing behavior, as the attack proceeds without a clear leader or specific orders given by any one participant. Compy packs do not appear to have a distinct hierarchy at all, with all the flock members appearing equal in status. The closest they come to strategy or hierarchy is the use of one individual to distract a target; it is unknown if this “scout” is chosen by the pack, or if the same individual acts as “scout” every time. It is completely possible that any compy may “scout” a target, initiating an attack from other hungry members of the pack.

Although they are not intelligent, compies do appear to have a means of communicating information about threats nearby. During the 1997 incident on Isla Sorna, one compy was struck without provocation by a telescopic shock prod wielded by InGen Harvester Dieter Stark. The following day, Stark threatened a compy with the shock prod; this time, it appeared to recognize the weapon as a danger and fled immediately. While this may have been the same compy, the Harvesters had at that point traveled some distance from the initial encounter. If the second encounter was indeed with a different pack than the first, this suggests that separate social groups of compies can communicate with one another to relay information. If the two encounters were instead with the same flock as it stalked the Harvesters, it instead implies a strong associative memory in Compsognathus, a trait which would help it recall threats it had survived in the past and avoid them.

The Lost World Movieplay describes compies as sometimes feeding on their own kind. This is unusual for such a social animal, but there are circumstances that would make it believable. For example, a compy might eat a rival’s young, or they may cannibalize weak or injured members of their flocks. The latter would make a predator attack less likely, protecting the group as a whole by killing and eating potential targets among their number.

Reproduction

Compsognathus reproduction is probably rapid. The male most likely advertises his fertility using his body colors, such as his red dewlap, which becomes enlarged and flushed with color during the courtship season. Compies in courtship color have been observed in late December, but appear to fade back to their normal color by the end of March, indicating a mating period during the dry season. They resume courtship colors again by June. This suggests multiple short breeding periods throughout the year, spaced apart by about three to four months.

Mating is accomplished using cloacae which are located between the hips and tail. As with all dinosaurs, this species lays eggs; theropod eggs are ovoid and birdlike, an evolutionary trait that helps them avoid rolling away from the nest. Compies generally nest in sheltered areas where other animals cannot easily reach them, making reproduction difficult to observe. Their nests were observed by Darius Bowman between December 24, 2015 and late March 2016; they are built from grasses and other plants, and the number of eggs laid is surprisingly small: his illustrations show only two eggs in a nest. The eggs are fairly large for the size of the animal that lays them, and are patterned with splotches like those of some ground birds.

In June 2016, compies with bright red dewlaps were seen gathering shiny objects that they used to decorate their nests. Larger shiny objects appear to be more desirable, and compies will sometimes fight over them. While these brightly-colored compies are often believed to be males, at least one was referred to as a female, suggesting that both sexes decorate their nests to attract mates. No eggs were yet seen in the nests, which were located in sheltered places inside the derelict Jurassic Park Visitors’ Centre; due to structural damage these nests were destroyed before any eggs could be laid.

The smallest dinosaurs have fairly short incubation periods, measured in weeks; eggs observed by Darius Bowman were laid and hatched within a period of twenty days. This would mean compy eggs laid in the late dry season would hatch before the wet season arrived. It is unknown what kind of parental behavior is exhibited. Most dinosaurs show very strong parental instincts like those of crocodilians, and as InGen compies appear to lay fairly few eggs, they likely exhibit K-selection behavior, caring intently for their young.

Stable populations of Compsognathus have existed on Isla Nublar and Isla Sorna throughout the past, but eggs, hatchlings, juveniles, and even subadults have never been witnessed directly. Instead, these populations always seem to consist entirely of adults, even shortly after breeding periods. This suggests that compies grow to skeletal maturity very quickly after hatching, which in turn means that they likely reach sexual maturity after a short time. This is probably what has allowed Compsognathus to flourish.

Communication

Compsognathus is a highly vocal dinosaur, making a wide range of birdlike chirps, squeaks, clicks, and whistles. Most of these serve to communicate information to its packmates, but it also uses aggressive hisses and jaw-gaping displays to confront potential enemies. When backed by its hidden packmates, a Compsognathus acts boldly toward threats.

Many people mistakenly assume that lone compies make “friendly” chirping and chittering sounds toward other animals, or otherwise attempt to communicate with members of other species. In reality, a compy is almost never alone, and these noises are meant to distract the target and communicate with the compy’s hidden packmates. Once the pack has begun stalking the prey in the open, they will make high-pitched cries to one another, which appear to serve as a kind of encouragement. The compies embolden one another, increasing the efficiency of their hunt.

In addition to communicating during hunts, compies will chirp and squeak to one another while traveling or foraging, and often drink communally from ponds and brooks. This likely reinforces social bonds between members of the pack. They will also let out high-pitched whines and squawks when frightened, which alerts other compies nearby to danger. If a whole pack flees from a threat, such as a natural disaster, they are often seen making high leaps in addition to alarm cries. These leaps not only help them cover more ground and clear obstacles, but acts as a form of visual signalling that ensures the pack members can all see one another when fleeing through tall grass or brush.

Ecological Interactions

Because of its small size, Compsognathus is placed low on the food chain regardless of what environment it is in. It is not at the very bottom, however; it still feeds on even smaller creatures, such as lizards, small snakes, and invertebrates. This regulates the populations of various species, including disease-carrying insects such as mosquitoes. Compy packs living in wetlands may eat large numbers of mosquitoes, reducing the populations of these insects and protecting other animals from disease. Of course, compies in the Jurassic period are known to have been affected by blood-drinking parasites such as mosquitoes too; it is unknown if modern mosquitoes affect them similarly. In addition to eating insects, compies will scavenge carrion, dung, and other detritus, which can help to reduce sources of disease in their environment.

While Compsognathus may act cooperatively to bring down prey much larger than itself, this is probably ineffective against well-defended prey items. As a result, there are relatively few larger animals that compies can feed on, restricting their diet. Instead, compies are probably preyed upon by the medium-sized predators in their environment. To survive, they rely on plant life; thick foliage and tall grasses are capable of hiding these striped green animals quite well, so a compy’s life may depend on the health of local flora. With hunters such as Velociraptor and Dilophosaurus living in the same territories, compies must be vigilant, ever ready to run and hide. They make use of their acute senses of vision and smell along with their agility and speed to evade danger. Even so, they are frequently eaten by faster animals. In the modern day, compies in Africa contend with predation from the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), the fastest land animal alive today.

If ecological changes bring new predators into their habitats, they may vacate and seek new nesting grounds. This was observed between March and June 2016, when compies nesting around the Camp Cretaceous campsite abandoned it in order to seek more secure territories where the newly-escaped Scorpios rex would be less of a threat. Their nesting grounds in the Visitors’ Centre were shared by a Velociraptor, but they nested in the building’s upper levels where the raptor could not reach them. Compies have been known to successfully share territory with Velociraptor by using their size and speed to evade capture. This probably benefits them as the raptors keep away other creatures that could threaten a compy.

Predators abounded on Isla Nublar and Isla Sorna for decades, and Compsognathus would have been threatened by at least some of them. Carnivorous animals known from their territories include dinosaurs such as Monolophosaurus, Herrerasaurus, Teratophoneus, Baryonyx, Allosaurus, Carnotaurus, Spinosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus; while many of these animals were large enough that compies would probably not be viable prey, they could still be a threat. Among the largest of these predators was Tyrannosaurus; compies have been observed fleeing from its movements and become wary when they smell its urine. Compies will also flee from Carnotaurus. Their homes may be disturbed by the behavior or large theropods; a territorial clash between a Spinosaurus and Tyrannosaurus in 2001 was noted to have driven several compies out from their nests. Other carnivores that inhabit the same areas as compies include the pterosaurs Pteranodon and Dimorphodon, as well as modern-day animals including Isla Nublar’s largest native predators the common boa constrictor and brown pelican. A species of alligatoroid, possibly the giant Deinosuchus, may have inhabited similar territory on Isla Nublar as well. Compies are known to practice kleptoparasitism, a feeding behavior in which they steal food from other carnivores.

Although the compy normally feeds on small reptiles and insects, it may be able to bring down small mammals and dinosaurs (including birds) if it works in groups. Its habitat included mammals such as brown rats, goats, collared peccaries, and the Nublar tufted deer; birds such as the collared aracari, ducks, and various other species lived on the same islands as it. Reptiles, such as the milk snake and iguana, could potentially be killed and eaten by a few compies working together. Only the smallest of nonavian dinosaurs would have been easy to kill, with Microceratus being a potential target. Other dinosaurs were simply too large or too armored. Even the relatively defenseless Gallimimus could evade a pack of compies using its speed alone, and fatally trample those that were in the way.

Compies shared territory with armored giants such as Stegosaurus, Ankylosaurus, Peloroplites, Triceratops, Pachyrhinosaurus, and Sinoceratops, the sauropods Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Mamenchisaurus, and the hadrosauriforms Parasaurolophus, Ouranosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Corythosaurus. While these animals are vastly larger than a compy’s potential meals, they could benefit in other ways. Compies would be able to eat from the droppings of these huge herbivores, and eat the swarms of insects that dung surely attracted. This would keep the local environment clean and sanitary. Living in the shadows of these titans also keeps the compies safer from other predators. The pachycephalosaurs Stygimoloch and Pachycephalosaurus, on the other hand, would not be such welcome neighbors; they are small enough to notice and attack a compy, strong enough to be too dangerous to prey on, and notoriously cantankerous.

Curiously, Compsognathus does not show any fear of Troodon pectinodon, and the latter does not appear to prey on compies. In fact, compies often show up after a T. pectinodon kill. This suggests that a symbiotic relationship between the two may exist. Compies might feed on the victims of their larger neighbors, but could also eat the insects that would surely be attracted to the nests. While the nature of their relationship is entirely speculative at this point, it hints at a unique aspect of these animals’ lives that has yet to be fully explored. Compsognathus does not appear to have a similar relationship with Troodon formosus, which has very different biology and behavior. However, T. formosus greatly resembles a very large compy, and its juveniles are visually hard to distinguish from adult compies.

Cultural Significance

Symbolism

Compsognathus is perhaps best known for its small size; for over one hundred years after its discovery, it was the smallest nonavian dinosaur known to science. While commonly compared to chickens, adults actually grow closer in size to turkeys. Still, they are frequently depicted or described in children’s literature and dinosaur media as chicken-like. This makes it a useful way to demonstrate how birds may have evolved, though Compsognathus itself is not a direct ancestor of any living birds. This species is also used to demonstrate the important fact that not all dinosaurs are extremely large.

Due to its small size, Compsognathus is a go-to creature for the dinosaur-themed movie or video game seeking to populate its world with a smaller scavenger or minor threat. It is often seen as a cute animal, so it has long been a staple in both professional and amateur paleoart, especially in scenes seeking to explore the often overlooked details of the ecosystem.

Since its de-extinction, Compsognathus has been frequently compared to rats because of its size, adaptability, high reproductive rate, and capacity to be a pest to humans. Because of this, it has symbolically become representative of many of the same things as rats; compies may be seen as symbolizing unclean living conditions, for example, because they can flourish in places with excess garbage. As one of the de-extinct animals most capable of adapting to human habitation, they also symbolize the difficulty of dinosaur removal in the eyes of anyone who wishes the animals gone.

In Captivity

Despite seeming like an ideal captive animal, the compy has had little success in de-extinction theme parks. It was originally planned by InGen to feature in Jurassic Park; while some maps show a paddock designated for this species there is no evidence that the enclosure was actually built by 1993. As a matter of fact, InGen leaders had not yet given the all-clear for Compsognathus to be imported to Isla Nublar, so their existence on the island was unplanned. In 1997, the company under Peter Ludlow‘s leadership collected a few compies from Isla Sorna for exhibition in Jurassic Park: San Diego, but as this plan was sabotaged the compies were never put on display.

Isla Nublar’s compies roamed more or less unchecked during Jurassic World‘s construction, and were barely contained by the time the park neared completion in 2004. Eventually they were housed in a pen to the north of the island, though any plans to directly exhibit them remain unknown. Frequent escapes proved an obstacle to keeping them in captivity, and this may have been part of the reason they were not made into a park attraction. In late 2015, Jurassic World closed indefinitely; it is unknown whether this dinosaur was ever exhibited during the ten-year course of park operations.

In theory, compies would be one of the most manageable dinosaurs to keep on exhibit; their small size means that they do not require vast amounts of space, and they are exceptionally easy to feed. In fact, they will not only accept most commercially-available foods, but will also feed themselves in their habitats if given the chance. Compies will eat many types of small invertebrates as well as carrion and the dung of other animals. This makes them useful in keeping habitats clean and free of disease-carrying insects, as well as a convenient way to dispose of animals that have died of natural causes. The bodies of animals that died from diseases, of course, should be disposed of following sanitary procedures and not fed to captive compies.

Visitors to dinosaur parks would also, again in theory, enjoy the compies for their exuberant and inquisitive behavior, birdlike appearance, and cute squeaking noises. Between the ease of housing this dinosaur, the low cost of maintaining it, and the appeal to tourists, it seems at first as though this is the perfect dinosaur for captivity. Unfortunately, the very quality that makes it so appealing is also the greatest challenge for most dinosaur parks. It is very small, and despite not being very intelligent, it is an accomplished escape artist capable of foiling most attempts to fence it in. This may be because most dinosaur parks have historically been prepared to house gigantic life forms, not small ones; compared to the average zoo a dinosaur park is embarrassingly unequipped to contain animals the size of poultry.

Escaped compies are not that hard to find and capture, since they are naturally curious and will often approach humans willingly. They can be restrained using basic implements suitable for other small animal species. Again, this seeming advantage presents an equal disadvantage: compies will approach any human fearlessly so long as they do not learn to associate humans with danger, meaning tourists are just as likely to have an encounter with an escaped compy as staff members are. People unfamiliar with animal handling may try to interact with the cute animal, which can result in a bite or scratch. From here, the pathway to bad publicity is obvious and inevitable.

Science

The discovery of Compsognathus was an important one to paleontology for a variety of reasons, not nearly the least of which was its proximity to the primitive birdlike dinosaur Archaeopteryx. The anatomical similarities were striking, and Archaeopteryx was clearly related to early birds. Together, these theropods illustrated the possibility that birds are theropods, rather than cousins to the reptiles. Today virtually all evolutionary biologists understand the link between animals such as Compsognathus and modern bird species. While Compsognathus is not a direct ancestor to birds, it is a reasonably close relative and serves to demonstrate how similar these types of animals are to one another.

It also was one of the first truly small dinosaurs to be found, which helped to highlight its birdlike anatomy. Most of the well-known dinosaurs prior to this were the larger species; not only were these probably easier to find, their dramatic size helped fund research into them. Compsognathus drew attention to the smaller dinosaur species, standing apart from other dinosaurs known at the time for its diminutive stature. It was also the first theropod known from a mostly-intact skeleton, likely due to its small body enabling most of it to be preserved at once. Since its discovery, paleontologists have found dozens of tiny dinosaur species, some even tinier than Compsognathus.

The rock formations where this dinosaur is found contain remarkably well-preserved fossils, which have given fantastic glimpses into life in the European archipelagos that existed during the Jurassic period. Compsognathus was actually one of the largest dinosaurs in its habitat at the time, since it lived on small tropical islands where big animals would have been unable to thrive.

In the Genetic Age, this was one of the species studied in detail by Dr. Laura Sorkin in the early ’90s. She considered it her favorite due to its similarity to the chickens from her family’s farm. She speculated that it might have originally had feathers; currently, there is no direct paleontological evidence for or against it, since some compsognathids were wholly or partially feathered but some may have lacked feathers. As the first compsognathid to be added to InGen’s genetic library, it is a notable step forward in the history of paleogenetics. Multiple genetic variants may have been created, at least one of which possesses venom glands.

Politics

Its fate was up for debate between 2015 and 2018, particularly after the 2017 reawakening of Mount Sibo put its survival in jeopardy. As a carnivorous species (and one with noted historic containment difficulties), it was considered more controversial, and some politicians and public interest groups suggested leaving it to die while saving herbivorous species only. The United States and Costa Rican governments, along with Masrani Global Corporation, took minimal action to protect this dinosaur from extinction.

The Dinosaur Protection Group aimed to save it along with the remaining de-extinct species, aided by Benjamin Lockwood of the Lockwood Foundation; his financial aide Eli Mills turned the project to his own aims with the help of big-game hunter Ken Wheatley. Compsognathus is hardly “big” game, but its potential worth was still noted, and so a few of these small carnivores were captured by Wheatley to sell on the black market. However, none are confirmed to have been sold before the auction was interrupted by DPG activists. The DPG’s leader, Claire Dearing, had noted from the early days of her career at Jurassic World that the small size of a compy would make it easier to smuggle than most dinosaurs. Between their small size and rapid reproductive rate, compies have a high potential to become an invasive pest species. They are also a common item on the black market, and thus subject to serious animal rights issues.

Resources

Having been genetically engineered from ancient DNA hundreds of millions of years old, Compsognathus possesses unique biochemical properties that can be used to derive novel biopharmaceuticals. However, what compounds it may yield are not yet known. Its venom, which can cause mild disorientation in humans, may be of significance. This may also be one of the reasons for which it is sold on the black market.

While its potential as a de-extinction attraction is high due to its cute appearance, it has not yet been truly tested in captivity to see just how successful it can be. However, its ability to eat dung, carrion, and insects means that it can be used as an ecosystem service, keeping the habitats of other animals clean. Biological pest controls are considered more environmentally friendly than chemical ones, making Compsognathus a cost-saving measure in the delicate ecologies of de-extinction parks. They are commonly found in the illegal pet trade.

This dinosaur may also be a pest. Since it acclimates well to disturbed areas and is incurably tenacious, it may chew on electrical wires and other infrastructure, causing damage such as power outages. Its quick breeding rate and evasive behaviors make it infeasible to exterminate completely, so people must instead learn to cope with its existence should it establish itself in an inhabited area. They are often found rifling around towns and suburbs in search of food, so they may be attracted to garbage and other refuse.

Safety

A lone compy does not pose significant threat to an adult human, though children and babies are at risk. Still, even one by itself can deliver a painful nip if it gets into an aggressive mood. Its bites may be mildly venomous; no direct deaths from envenomation have been reported, with the main symptoms being disorientation and imbalance. If you are bitten, and you are in a relatively safe area, move slowly and carefully until the symptoms wear off; sit down if you can. Having other people around to help you will ensure you do not fall and injure yourself, which can be dangerous in the wild.

Handling compies is a bit of a chore since their behavior is unpredictable, but they can usually be dealt with by trapping them in a small blanket or towel. They can be handled more easily this way since they will be unable to bite or claw at you. When capturing a compy, bring a small cage such as a cat carrier with you to hold it. However, if you were not planning on catching compies and happen to run into one, you can probably still fend it off. If it attacks, it will probably jump up to try and bite exposed skin. You can fairly easily knock it away with your foot or by using your arm to shield yourself, but it may try to latch onto your limb to avoid being struck. Should it catch hold of you, remove it by holding it from behind, with one hand at the back of its head so it cannot swivel around and bite. Dinosaur behavior experts may be able to soothe this animal while handling it, but unless you are one of them, it is more advisable to toss the compy away from you and then put distance between yourself and it. However, if it chases you, outrunning it may not be an option as it is quite fast. You may be able to scare a compy away by waving your arms, shouting, and otherwise making yourself appear big and intimidating. Bright lights can distract it.

Compies are more of a threat when they are in groups, as this emboldens them even further and allows larger doses of venom to be gnawed into your bloodstream. More bites will result in greater disorientation, which is exacerbated by blood loss. If a group of compies is coming after you, some of the same strategies for dealing with one alone may still be effective: intimidating them or distracting them can delay their attempted attack. Do not rely on these tactics alone, though; a lone compy might be frightened off, but a pack is more determined. They usually congregate like this when seeking food or safety, so they probably are either hungry or stressed. This will naturally make them more aggressive. If you are carrying food, this could be the reason they are chasing you. This does not just include meat, but anything else they might smell. If they are after your food, thow it far from your path. To prevent this from happening in the first place, always seal food in bags while hiking in the wild, and when at camp do not store food where animals can access it. Many people feed compies because they are cute, which can lead to them associating humans with food. They are not the smartest of theropods, so sometimes they may skip the step in which the human voluntarily provides the food and go straight to the eating part.

A few serious incidents involving compies have been reported. The first was Cathy Bowman, a young British girl who was attacked on Isla Sorna in late 1996. The second was Dieter Stark, a big-game hunter hired for the InGen Harvester expedition in 1997. In both cases, the human was at fault for the attack. Cathy Bowman fed a wild compy, drawing in a larger group which attacked her when the food ran out. Her attack required hospitalization, though she survived. Dieter Stark harassed and provoked compies during the Harvester operation, and after wandering far from his team he was attacked by a large group of compies. He eventually succumbed to disorientation and was killed. In more recent times, the Biosyn representative Lana Molina was killed in a rare unprovoked attack in 2016.

To avoid being attacked, follow the same guidelines that you would with other carnivorous animals. Do not feed or harass them, and keep a respectful distance. If you see one, do not give in to the temptation to play with it no matter how cute it appears. These dinosaurs are rarely seen alone; they travel in groups and you should too when venturing through the woods. Make regular headcounts when in their territory. Extra protection should be given to more vulnerable people, such as children or the elderly.

Behind the Scenes

The character Dr. Robert Burke, the paleontologist featured in The Lost World: Jurassic Park, misidentifies this species. He refers to it as Compsognathus triassicus (or Procompsognathus triassicus, per the script). This may have been a gag for the film. Dr. Burke shares an uncanny resemblance to real-life paleontologist, Dr. Robert T. Bakker, who paleontological consultant Dr. Jack Horner has a long-standing rivalry with. Dr. Horner describes the character here:

“In TLW you may have noticed a paleontologist in the movie that wore a big straw hat and had a beard…this character was based off a real paleontologist that often disagrees with me … I had him eaten too! (laughs)” — From an interview on Dan’s JP3 Page on April 5th, 2001

The misidentification of Compsognathus in the film may have been a joke on the part of Dr. Horner intending to make the character Dr. Burke (and by extent Dr. Bakker) appear incompetent, but as this would be a relatively obscure joke, it is more likely a blooper. The species Procompsognathus triassicus appears in the novel versions of both the first two films, and members of Universal Studios may simply have confused the two animals. However, the animal was correctly identified as Compsognathus longipes on the InGen IntraNet website, which was created in 1997 at the same time the film was being produced.

Disambiguation Links

Compsognathus longipes (SF-Ride)

Compsognathus “triassicus” (JN)

Compsognathus “triassicus” (CB-Topps)

You may also be looking for…