Among the most well-studied of dinosaurs, Triceratops (meaning “three-horned face”) is a large species of chasmosaurine ceratopsid, or horn-faced, dinosaur. It lived in North America during the late Cretaceous period 67 to 65.5 million years ago alongside other well-known dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex, being among the last non-avian dinosaurs to live on Earth before the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event. It is sometimes nicknamed the “trike,” particularly following its de-extinction by International Genetic Technologies. During its own time, it was among the most common animals; Dr. Robert Bakker estimated in 1986 that Triceratops alone constituted five-sixths of dinosaurian megafauna in North America by the end of the Cretaceous period.

Among the most well-studied of dinosaurs, Triceratops (meaning “three-horned face”) is a large species of chasmosaurine ceratopsid, or horn-faced, dinosaur. It lived in North America during the late Cretaceous period 67 to 65.5 million years ago alongside other well-known dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex, being among the last non-avian dinosaurs to live on Earth before the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event. It is sometimes nicknamed the “trike,” particularly following its de-extinction by International Genetic Technologies. During its own time, it was among the most common animals; Dr. Robert Bakker estimated in 1986 that Triceratops alone constituted five-sixths of dinosaurian megafauna in North America by the end of the Cretaceous period.

It was discovered in the Lance Formation of Wyoming by cowboy Edmund B. Wilson in 1888. Alarmed by the sight of a huge horned skull embedded in a ravine wall, Wilson lassoed one of the horns to pull it down. The horn broke off in the lasso, but the skull fell to the bottom of the ravine. His employer, Charles Arthur Guernsey, was impressed by the horn and happened to show it to paleontologist and fossil collector John Bell Hatcher. A year prior to this, a pair of horns belonging to the animal were found by George Lyman Cannon near Denver, Colorado, but were identified by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh as a new species of Pliocene bison called Bison alticornis. After Marsh learned about Wilson’s skull, Marsh sent Hatcher to recover it.

Having received the skull from Hatcher, Marsh recognized that it was a dinosaur and named it Ceratops horridus, meaning “rough horned face.” Shortly after, paleontologists discovered that the head possessed a third, shorter horn on the nose; realizing that it was not a species of Ceratops but a new, previously unknown genus, Marsh named it Triceratops, meaning “three-horned face,” in 1889. At the time he believed that his 1887 “bison” horns were examples of Ceratops remains, but eventually acknowledged that these, too, belonged to Triceratops.

The sturdy skull of this dinosaur ensures that many fossil remains survive the test of time, so paleontologists found much material to work with over the years. Fossils have been found in several American states; after Colorado and Wyoming, they were discovered in South Dakota and Montana. In Canada, they have been found in Alberta and Saskatchewan. They are particularly common in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, which is famous for yielding abundant Triceratops remains.

Between 1889 and 1891, a further thirty-one skulls were laboriously collected by Hatcher for Marsh’s benefit. The variations in skull and horn shape prompted Marsh to name eight new species of Triceratops and even a new genus he called Sterrholophus. None of Hatcher’s new skulls were identified as the original species, T. horridus, by Marsh. After Marsh’s death, Hatcher tried to reconcile the many new species more sensibly, but fell sick and was unable to complete his work. Hatcher’s study was completed by paleontologist Richard Swann Lull, and by 1933, the remains had all been classified into taxonomic groups. One group of species was defined by a larger nasal horn, while another group was defined by an increased skull size with larger brow horns and a smaller nasal horn.

During the 1980s, scientists began to theorize that the many species of Triceratops might be better explained as variations within only one or two species. In 1986, paleontologists John Ostrom and Peter Wellnhofer published a paper suggesting that the original Triceratops horridus was the only species after all, and that factors such as age, sex, and conditions of fossilization had produced the variety of forms classified as different species earlier. Their conclusion was challenged by Catherine Forster a few years later; her studies determined that there were actually two species, T. horridus and T. prorsus. A 2009 study by John Scannella and Denver Fowler supported Forster’s conclusion, which is still widely used by the scientific community.

These two species can be told apart by their horn and frill shapes. The slightly larger T. prorsus has brow horns which rise prominently before curving forward, a larger nasal horn and taller snout, and a somewhat taller frill, while the smaller T. horridus has more horizontally-aligned brow horns which curve slightly downward, a smaller nasal horn and shallower snout, and a lower frill. Some paleontologists suggest that the bony parts of the horns would have supported larger keratinous structures and may have looked somewhat different than implied by fossil remains.

The ceratopsid genus Torosaurus is considered by some paleontologists to represent an older, more mature growth stage of Triceratops. This conclusion was supported by InGen’s Dr. Laura Sorkin in 1993, who documented evidence in de-extinct specimens; however, later sources have generally disagreed with Sorkin’s conclusion. Nonetheless, in 2009, Scannella and Jack Horner stated with confidence that Torosaurus should be considered a mature growth stage of Triceratops, which is sometimes called the “toromorph” stage. Since then, new papers have been published supporting the opposite theory, that these are two different dinosaurs. The debate as to whether Torosaurus is a scientifically valid genus has not yet been resolved.

The ceratopsid genus Torosaurus is considered by some paleontologists to represent an older, more mature growth stage of Triceratops. This conclusion was supported by InGen’s Dr. Laura Sorkin in 1993, who documented evidence in de-extinct specimens; however, later sources have generally disagreed with Sorkin’s conclusion. Nonetheless, in 2009, Scannella and Jack Horner stated with confidence that Torosaurus should be considered a mature growth stage of Triceratops, which is sometimes called the “toromorph” stage. Since then, new papers have been published supporting the opposite theory, that these are two different dinosaurs. The debate as to whether Torosaurus is a scientifically valid genus has not yet been resolved.

Triceratops horridus is notable for being the first species successfully brought back from extinction. InGen paleogeneticists Drs. Laura Sorkin and Henry Wu succeeded in cloning T. horridus in 1986 in a laboratory facility on Isla Sorna, Costa Rica using ancient DNA obtained from the blood of engorged female mosquitoes trapped in Mesozoic amber samples. As of June 11, 1993, InGen had created up to Version 2.05 of the animal. This well-defended creature has bred prominently throughout the history of de-extinction; it is one of the few de-extinct animals that has maintained a healthy breeding population without human intervention following the 2015 Isla Nublar incident.

Triceratops is the official state fossil of South Dakota and the official state dinosaur of Wyoming.

Description

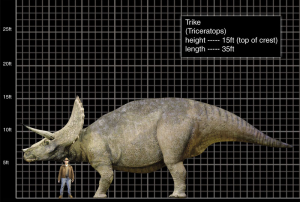

Triceratops is among the biggest of the ceratopsians, with fossilized adults reaching up to nine meters (29.5 feet) in length and three meters (9.8 feet) to the top of its head. InGen’s specimens grow between 6.1 and 9.1 meters (20 and 30 feet) long and 2.7 to 3.6 meters (9 to 11.8 feet) tall. At maximum size, they can reach an impressive 10.5 meters (34.4 feet) long and 4.5 meters (14.8 feet) tall, exceeding the dimensions of fossil specimens. Weight estimates for InGen’s creatures range from six to eleven tons (5,443 to 9,979 kilograms). This actually falls short of some paleontological estimates for the animal’s weight, which has been estimated at 6.5 to 13 U.S. short tons (13,000 to 26,000 pounds, 5,896.7 to 11,793.4 kilograms).

The most distinctive feature of the Triceratops is its huge, heavy skull. Unlike many ceratopsids, the skull is made of solid bone rather than having holes (called fenestrae) to make it lighter in weight, excepting possible individuals that enter the toromorph stage. The skull of this animal can make up nearly a third of its overall length, reaching 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) long in the largest specimens.

The massive head is wedge-shaped, narrowing toward the front where it forms a high-beaked mouth. While the beak itself is toothless, the jaws farther back contain teeth designed for slicing through food. These teeth, like with most dinosaurs, would wear down and become replaced over time. Triceratops uses thirty-six to forty teeth at a time, depending on its size, and the teeth are arranged in columns called batteries. When the uppermost tooth wears down, it falls out, the one beneath now ready for use. Because of this arrangement, an adult trike can have up to eight hundred teeth in its mouth at once, stacked on top of each other. Its tongue is thick, muscular, and brownish, with a sandpaper-like texture. On the snout is a small conical nasal horn, and over the eyes are a pair of much longer (up to one meter, or 3.3 feet long) brow horns; these are covered with keratin, giving them a cracked fingernail-like appearance. The horns are not extremely sharp, but are sturdy. The animal’s eyes are birdlike rather than reptilian, with large circular pupils and yellow or amber-colored sclerae. It has relatively poor eyesight.

The skull extends backward to form a short but solid circular frill formed from the outer squamosal and inner parietal bones, which defines this animal’s imposing profile when viewed head-on. The frill is decorated around the edge with small bony protrusions called epoccipitals. In Triceratops, these are wide at the base and triangular, forming a saw-tooth fringe. InGen’s specimens have between eighteen and twenty-one epoccipitals as adults. In the journal of Dr. Laura Sorkin, a drawing depicts a specimen with twenty-three distributed asymmetrically on its frill; this pattern has never been seen elsewhere. Many specimens have cheek horns called epijugals located near the base of the frill; most Triceratops have two on either side. Some lack these, however.

As with many chasmosaurines, the portly body of Triceratops is mostly nondescript. Some have noticeable osteoderms on their bodies, but many specimens lack these. Paleontological evidence suggests that it would have had quills on its body, but these are absent in InGen animals as are similar forms of integument. As these features were unknown until more recently, InGen would probably have assumed that they were an unwanted mutation had they appeared on any of the cloned specimens.

The powerful and stocky legs of the trike end in broad feet with distinct hoofed toes; cloned animals generally have rounder feet with shorter toes than their fossil counterparts, appearing somewhat elephant-like. InGen’s specimens differ from fossil ones in the number of toes on each foot. Fossil Triceratops have three toes on each front foot and four on each hind foot, while InGen’s specimens have been observed with up to five toes on the front feet and usually three on the hind feet. Its legs are powerful, and it can reach speeds of ten miles per hour when running.

This animal’s tail is relatively short and not extremely flexible. It serves little purpose other than balance, being unable to swing as an effective weapon like its fellow herbivores Stegosaurus and Ankylosaurus.

Coloration in this animal is usually fairly drab, chiefly because of its tendency to roll in dirt and dust which coats its body. It is naturally a gray-blue, gray-green, or gray-brown color, with some patterning on the dorsal side and flanks; the osteoderms and horns are usually lighter than the rest of the body. Others have been seen with beige or tan skin, featuring a pale brown saddle marking and stripes on the rear half. Shading of the body color also varies; while many are lighter-colored, numerous dark-colored individuals are known. In the darkest-skinned trikes, white stripes along the length of the dorsal side from neck to hips can stand out vividly against the gray skin, and the head often has a white tint. There may be circular spots and blotches on some animals; coloration is believed to be genetically linked.

The head is surprisingly not brightly colored, with the frill being more or less the same color as the rest of its pelt. Some specimens, most of which were bred for Jurassic World in the twenty-first century, feature pale teal markings around the eyes. Unlike many dinosaurs, there is minimal countershading.

Growth

Because trikes are such successful breeders, their growth stages are remarkably well understood; the only real scientific unknown is the mysterious “toromorph” stage which has only been observed developing on one occasion.

Upon hatching, trikes are less than a foot long. At this stage, their coloration typically resembles what they will look like as an adult. The horns begin as small blunt nubs roughly an inch long, growing out as the animal ages into adolescence. The brain is about the size of a hazelnut at this age. Its epoccipitals are absent when it hatches, but in some specimens grow out relatively quickly. By the time it becomes an adolescent, at least some of the epoccipitals will have formed, signifying the approach of adulthood. Young trikes eat roughly 24 pounds of plant matter a day, with this amount increasing as they get larger. Juveniles can be told apart by the shape of their horns, which are straight and point upward. As they age, the horns will begin to curve forward. Hatchlings and juveniles may already show development of the epijugals, though often only one will have developed yet. Adults may have two. In general, the bony ornamentation on the trike’s head is more rounded in young animals, becoming sharper as they approach maturity. As the animal’s ornamentation grows, it will rub its horns and frill on objects such as trees to help shed the outer layers.

Most, if not all, of the epoccipitals will have formed by the time the animal is roughly seven or eight feet long, though the horns will still not have reached their full length. At this stage the frill is mostly developed, coinciding with the stage at which it will begin aggressive dominance displays with its neighbors. Development of osteoderms may also occur with age, though some trikes have these mostly formed in the juvenile stage and some never develop them at all.

Older animals have more prominent frills and larger epoccipitals, and adulthood is identified by the curvature of the fully-formed horns. At this stage, the horns curve forward and slightly downward before sweeping upward again, though how dramatic this wave-shaped pattern becomes varies with the individual. Adults’ frills also become marked with scars gained during intraspecific combat, older animals having dueled more of their own kind than younger ones. As it becomes advanced in age, the epoccipitals slowly wear away, and the horns hollow out.

For more than a century, some scientists have posited that the genus Torosaurus is not actually a real animal at all, but rather a growth stage of Triceratops. This speculative stage has been called the “toromorph” by some paleontologists who support the theory. The transition from standard adult trike to toromorph has been observed only one time; it is recorded in Dr. Laura Sorkin’s field journal in entry #2. She reports that the trike’s brow horns straighten and elongate and the beak becomes extended and more hooked, while the frill elongates into a heart-like shape and develops very large fenestrae. Sorkin hypothesized that these fenestrae, or holes, develop in the frill to compensate for its increased size. The epoccipitals disappear from the frill in this stage. It should be noted that the individual she recorded undergoing this transformation had an abnormally large number of epoccipitals, twenty-three, with ten on the animal’s right side and twelve on the left with a single one at the frill’s apex. Asymmetry in epoccipital distribution has otherwise not been observed in InGen’s Triceratops, and it is unknown if this individual’s unusual morphological traits as a standard trike adult were in any way related to its reaching the toromorph stage.

In any case, Torosaurus has been consistently treated as a valid genus separate from Triceratops in most material outside of Dr. Sorkin’s single observation. At present, there is no evidence to suggest that her case study was in any way representative of typical Triceratops ontogeny. Its exact growth rate is not known, but adulthood of the original animals hatched in 1986 was reached sometime before the summer of 1993; this suggests that trikes mature in seven years at most. Some animals that had hatched between 1995 and 2004 were still living in 2018, suggesting a lifespan of several decades. This is fairly consistent with fossil evidence.

Sexual Dimorphism

Fossil evidence has been used to argue that Triceratops expressed sexual dimorphism, usually with longer horns and larger frills indicating that the animals are male. However, the amount of individualism in fossil remains makes this difficult to prove. InGen’s specimens also demonstrate a fair degree of individualism; while both males and females have been identified conclusively, there is not currently a reliable way to sex the animals based on a quick visual observation. Color patterns may be more vibrant and extensive in the male, but since different genetic lineages have wildly different colors, this is not always useful.

Habitat

Preferred Habitat

The low-built, portly frame of this dinosaur gives it some difficulty moving in densely-forested regions, so it prefers grassland and semi-arid regions. Fossil evidence suggests that it flourished on fern prairies and floodplains during the late Cretaceous period, and that it avoided wetland due to being a poor swimmer. Its feet are poorly adapted for loose soil or mud, suggesting that it spent all of its time on solid ground. It is generally seen on open, flat areas of land; forests are commonly nearby, but it usually does not venture into them very often. Feeding behavior of this dinosaur impacts the local environment, with their favored plants being consumed and leaving just the scrub and grass. Dirt in their habitat becomes densely packed as they tread over it repeatedly.

For health reasons, they require sources of water in their habitat that are deep enough to bathe in. They can survive in desert areas, congregating around any bodies of water which they use their strength and size to dominate, and can withstand cold northern climates as well.

Muertes Archipelago

This species has the honor of being the first creature to become de-extinct, having been cloned successfully by InGen on Isla Sorna for the first time in 1986. Population statistics for Triceratops between 1986 and 1993 are mostly unknown; between 1988 and 1993, however, as many as five were transported away from Isla Sorna for exhibition in Jurassic Park on Isla Nublar. These included one of the eldest trikes, Lady Margaret, and a female named either Freda or Sarah depending on the source. Three juveniles may have been transported from Isla Sorna by 1993, but it is also possible they were bred on Isla Nublar. At least one toromorph-stage trike was reported by Dr. Laura Sorkin by 1993, but as it was never seen outside of her notes, it is presumed to have died at some point, either on Isla Sorna or on Isla Nublar if it was transported there.

In 1995, Site B was abandoned by InGen due to the impending Hurricane Clarissa. At the last point that InGen monitored Isla Sorna in 1993, there were ten living trikes on the island. While their location is unknown, they most likely inhabited the southwest, where most Triceratops were later found.

Satellite thermal mapping in 1997 located a population of Triceratops concentrated in central Isla Sorna; they were known to inhabit multiple parts of the island between 1997 and 2004. They were among the species targeted during the 1997 InGen expedition to Isla Sorna, with an adult male and four-foot-long juvenile being captured on May 28. This juvenile is sometimes dubbed Ralph, and is presumed to be related to the adult male. These two animals were captured in the northeastern part of the island near the game trail, and escaped the InGen Harvester encampment during the incident. They are the only trikes known from this area, but a female must have been present at some point in order for the juvenile to exist.

Sometime during May or June of 2001, Eric Kirby witnessed an adult or sub-adult Triceratops in the parking lot area of the Embryonics, Administration, and Laboratories Compound. This appears to have been a solitary individual. Another solitary adult Triceratops was seen a week or two later, sometime in June, in the island’s southwest; it was possibly the same animal.

On July 18, illegal chartered flight N622DC passed over a grassland area of western Isla Sorna; the passengers witnessed a population of twelve adults and subadults with two twelve-foot-long adolescents. Differing patterns in the adults suggest males and females, but individualism in Triceratops is not necessarily tied to sexual dimorphism. Nonetheless, the fact that this herd contained young means that it must necessarily have male and female adults. One of the Triceratops in this group, a lighter-colored adult, was browsing some distance behind the herd, and may not have been part of it. Two of the darker-colored adults, one with white stripes and one without, stood farther ahead of the herd but appeared to be moving in the same direction.

The junior novel Prey features a herd of Triceratops with multiple infants and at least three fully-grown adults (including at least one male) on December 30, 2001 living in southwestern Isla Sorna near Mount Hood. This herd was identifiable by spot and blotching patterns on their skin, unlike the stripe patterns of the animals seen on July 18. The infants would have hatched from eggs laid sometime about six months to a year prior.

Isla Sorna’s Triceratops population growth is reasonable between 1993 and 2001. In late 1993, there were ten living animals; by 1997, at least one breeding pair had managed to reproduce successfully. In the summer of 2001, there were at least fourteen animals still alive on the island, two of which were juveniles that would have hatched between 1997 and 2000. If the account in Prey is accurate, more animals may have hatched in late 2001. By early 2004, there were at least sixteen surviving female trikes on the island, including three older adults, one juvenile, and twelve other adults or subadults. It is unknown if any of the dark-skinned, striped trikes survived, or if the spotted trikes described in Prey survived in the event that they are canon. At least one gray-colored, wild-born female did survive.

Overall, there may have been forty or more trikes on the island by 2004, assuming that none of the groups discussed above had any overlap. Of course, it is more likely that many of the individuals seen between 1997 and 2001 had died by that time due to the effects of ecological overcrowding.

Between late 1998 and early 1999, InGen illegally bred dinosaurs and performed research on Isla Sorna in preparation for a reinvigorated Jurassic Park project under the banner of Masrani Global Corporation. This caused havoc in Isla Sorna’s already-fragile ecosystem, including the death of one of its tyrannosaurs on July 18, 2001. While the death of the tyrannosaur would have benefitted the Triceratops, the presence of many new herbivorous dinosaurs would have harmed them by competing for food. Their population likely suffered as a result.

The new Jurassic Park project, going under the name Jurassic World, required any surviving trikes on Isla Nublar to be relocated to Isla Sorna; it is not actually known if any of the two Nublar survivors were still alive by this point in 2002. Nonetheless, in 2004, the relocation of Site B’s trike population began. They were the second species to be relocated to Isla Nublar, after Brachiosaurus. Preparation began in January, and by the summer, fifteen adults or subadults had been successfully removed from the island. These included three older females named Hypatia, Johnson, and Curie; an adolescent female named Lovelace was removed from Isla Sorna by August at the latest. Curie and Lovelace had previously been members of the same herd on Isla Sorna. All of the sixteen relocated trikes were named after famous female scientists, suggesting that none of this population were males.

By May 30, 2005, the entire Triceratops population had supposedly been relocated off Isla Sorna. This included a light-gray female that hatched sometime while Isla Sorna was unmonitored, though that particular animal may have been one of the original fifteen relocated adults. It may also have included some of the island’s males, since the Isla Nublar population was able to continue breeding; alternatively, the males may have been cloned on Isla Nublar independently of the Isla Sorna immigrants. No trikes are currently known from the Muertes Archipelago, though the islands are closely guarded and civilians are not permitted in their waters, so a true census of the de-extinct animal population cannot be made.

Jurassic Park: San Diego

As the first animal ever successfully brought back from extinction, Triceratops was always destined for park exhibition. InGen’s first planned attraction was Jurassic Park: San Diego, located on property InGen already owned near the waterfront of the coastal city of San Diego, California. Due to the lack of information about the early Park plans, the trike exhibit is currently unknown, but it was probably meant to be a major attraction. Unfortunately, this incarnation of the Park was never opened, being abandoned not long after Triceratops was cloned in the mid-1980s. InGen instead relocated to Isla Nublar, a more exotic locale which CEO John Hammond preferred.

In 1997, after Jurassic Park: Isla Nublar failed due to corporate espionage, the new CEO Peter Ludlow planned to try and finish Jurassic Park: San Diego to save the company. During his expedition to Isla Sorna, an adult male Triceratops and its offspring were captured for exhibition. Intervention from animal rights activists ensured that the animals were not removed by Ludlow’s team. Ultimately, Jurassic Park: San Diego was never opened, and no Triceratops reached it.

Isla Nublar

Beginning in 1988, dinosaurs were shipped from Isla Sorna to Isla Nublar, with Triceratops among them. There were two regions of the island intended to be used as Triceratops paddocks; the northern one consisted of a large area of grassland and shrubbery (including heliconias, banana plants, and West Indian lilac), as well as patches of dirt, sparse forest, and a small river. It was bordered to the east by what would eventually be the Metriacanthosaurus paddock, separated from it by the main tour road and five- to ten-foot electric fencing. However, the western half of this paddock was separated from the eastern half by a branch of the main road, which likewise had electric fencing on its western side. On the eastern side, it had a wire fence. Animals were kept on both sides of the fenced road as of 1993, allowing Park staff to separate them from one another if needed. To the west, it was separated from the secondary Dilophosaurus paddock by a twenty-four-foot electric fence, and it similarly bordered the Tyrannosaurus paddock to the south. North of the paddock’s boundaries, there were no other animal ranges; a small area of land separated its northern boundary from the Park’s perimeter fence. In the southern part of the island, a secondary Triceratops paddock bordered the Jungle River to the north, and surrounded most of the Segisaurus paddock. It was separated from this smaller paddock by the main tour road and a concrete moat. To the west, it was bordered by a service road with a similar concrete moat. On all other sides, its borders were made up of the Park‘s perimeter fence.

Triceratops has the distinction of having had both the northernmost and southernmost paddock areas on Isla Nublar in Jurassic Park.

As of June 11, 1993, there were several living Triceratops on Isla Nublar. The eldest was a female dubbed Lady Margaret by her caretakers. At least one other adult female lived in the Park at the time. There were also at least three juvenile females, one of which was named Bakhita; another may have been named Emile.

Dr. Laura Sorkin’s notes suggest that, at one point, at least one of InGen’s trikes matured into the rare and poorly-understood “toromorph” stage, but this individual has never been seen outside of her journal illustration and may have resided on Isla Sorna rather than Isla Nublar. If it did live on Isla Nublar, it was no longer alive by June 11, 1993.

During the 1993 incident, the Triceratops were able to roam outside of their paddock area, but did not travel particularly far. Lady Margaret was hunted down and killed by the Park’s Tyrannosaurus during the incident; this left only one other adult trike on the island, an animal that was sick from plant toxins at the time.

InGen’s last recording of the island in 1993 showed only three surviving Triceratops, but whether the sick individual or Bakhita were among these remains unknown as InGen did not make not of the specimens’ identities. It is generally assumed that the sickly individual would have been easily preyed upon by the tyrannosaur, leaving only the juveniles. A 1994 cleanup operation reported on October 5 that there were only two remaining trikes on Isla Nublar.

In 2002, InGen returned to Isla Nublar having been bought by Masrani Global Corporation. In order to prepare the island for construction, many of the larger animals were shipped temporarily to Isla Sorna, including any remaining Triceratops. They were returned in early 2004; during January, they were prepped for transport, and fifteen females had been introduced to the island by the summer. They were housed in the central valley of the island, where the Gyrosphere attraction was planned. The eldest of this group was named Hypatia, with the next-oldest being named Johnson and Curie. In August, an adolescent female named Lovelace was introduced to the valley, bringing the total population to sixteen. Eggs and hatchlings were also held in the hatchery at the time. It is not known if any of Isla Sorna’s males were salvaged during that island’s ecological collapse; Isla Nublar did have males living there during the Jurassic World era, but they may have been bred on the island independently of the Isla Sorna rescue operation.

By the time Jurassic World opened to the public on May 30, 2005, all of the Triceratops from Isla Sorna had been transported to Isla Nublar. This was among the most prolific breeders on the island, possibly encouraged by Jurassic World’s staff due to the animal’s popularity in the Gentle Giants Petting Zoo. They lived here during the juvenile stage, being moved to the central valley during adolescence. In addition to the Gyrosphere area, adult trikes were exhibited in an attraction located west of there called Triceratops Territory. All of the animals seen in the Gyrosphere and Gentle Giants attractions had lighter-colored brown and beige patterning; the darker skin patterns may have persisted elsewhere on the island, or possibly became extinct.

As of December 22, 2015, there were at least sixteen adult Triceratops living in the Gyrosphere area of the valley and seven juveniles in the petting zoo. According to the database in Jurassic World: Evolution, the Tyrannosaurus was the only dinosaur left on the island at this point that had lived in the original Park; this would imply that the two trikes that survived as of 1994 were no longer living by 2015. However, the database has since been contradicted by film director J.A. Bayona in the case of at least one Brachiosaurus, introducing the possibility that other first-generation Isla Nublar animals may have still been alive.

The closure of Jurassic World following December 22 permitted the dinosaurs to roam the island mostly unrestricted. Without any staff members or adult trikes in Sector 3, juveniles in the petting zoo would have been at the mercy of the environment, and if they were not freed by the Jurassic World staff, there is a high chance that they did not survive. The adults remained in the north, with their herd basing itself out of Triceratops Territory near the Western Ridge. They continued to breed while in the wild; a female had laid five eggs as of March 2016 in what was once the Adventure Zone.

As of May 15, 2018, at least one of the surviving trikes was a female that had originally hatched in the wild on Isla Sorna. As of such, its date of birth is unknown. In the early summer of 2018, a juvenile was sighted in the area near Mount Sibo; promotional material suggests that there were possibly several juvenile trikes on the island that summer. These juveniles would probably have been a year or two old at best, having hatched some time after the island was abandoned. The number of adult males and females living at the time, however, is unknown.

On June 23, 2018, the desiccated remains of an adult Triceratops were seen in what was once Gallimimus Valley. Three living adults were seen near Mount Sibo. A deleted scene would have shown a young juvenile in the same area at that time, alongside its parent. They were driven toward the eastern cliffs by the volcanic eruption that took place the day. A further three adults and one juvenile were removed from Isla Nublar on June 23 by means of the S.S. Arcadia; any left living on the island likely died either due to drowning, volcanic debris and other volcanic hazards, or the loss of their food sources.

The juvenile was cosigned by Craig Allison and logged into the ship’s manifest at 13:41, held in Container #24-1006-0481 (Cargo #88384). It was weighed at 246 kilograms. One of the adults, which was highlighted in yellow possibly indicating a health issue, was cosigned by Gonzalo Sanchez at a later time of 13:55, which counterintuitively means it was loaded on earlier (the cargoes were logged in reverse order). This adult was held in Container #25-1019-5410 (Cargo #43927) and weighed at 5,100 kilograms, making it quite underweight.

Mantah Corp Island

While Jurassic World operated from 2005 to 2015, InGen’s rival company Mantah Corporation operated its own facility for more nefarious purposes on the privately-owned Mantah Corp Island east of Isla Nublar. De-extinct life was poached from InGen facilities for testing and exploitation, housed in several biomes managed by advanced technology. Surprisingly, no Triceratops were ever seen in this facility during the years the company was poaching assets, suggesting that Mantah Corp failed to acquire this popular animal.

Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary

In the summer of 2018, de-extinct animals made their way into the wild, and the technology to create them went open-source in the global market. Natural and captive breeding (the latter of which was highly restricted) allowed the dinosaurs to proliferate, and Triceratops was eventually reported from multiple continents. This was an issue for people living in the affected areas, and governments of those countries were pressured to take action. Biosyn Genetics, long considered an alternative to InGen, rose to the occasion as its rival collapsed. Multiple nations’ governments contracted Biosyn to work alongside the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife to safely contain the animals. Once captured, these creatures could be shipped to secure facilities managed by Biosyn or the DPW. The largest such facility was the Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary, located in privately-owned Biosyn Valley in the Dolomite Mountains. Biosyn’s headquarters were located here, allowing them to easily keep watch over the animals.

Triceratops was among the species housed by Biosyn. They inhabited the forested parts of the valley near its rivers and lakes, grazing on the native plant life such as the abundant ferns. New additions came in regularly, such as a number in early 2022 rescued from an illegal breeding operation in the United States. In the spring of 2022, a wildfire occurred in the valley, damaging their habitat and necessitating an evacuation. Animals were herded into emergency containment until the fire had subsided. After this incident, the United Nations took over supervision of the valley. Despite the changes to leadership, the animals in the valley live mostly as they did before.

Black market

Between 1997 and 2018, the islands in the Gulf of Fernandez were affected by poachers; it is unknown if any of them managed to secure any trikes for their buyers. Such large and aggressive animals would not be easy to contain as adults, making it unlikely that these were among the species captured by less well-funded poachers.

The first confirmed case of Triceratops outside of the Gulf of Fernandez were a group of three adults (with at least one weighing 8,100 kilograms or 8.9 U.S. short tons) and one juvenile (weighed at 246 kilograms, or 524.3 pounds) which were collected from Isla Nublar by mercenaries led by Ken Wheatley operating at the behest of Eli Mills. On June 23, 2018, the animals were removed from the island by means of the shipping vessel S.S. Arcadia and delivered to the Lockwood estate near Orick, California. One of the adults was the mother of the juvenile (either biological or adoptive). The juvenile had been specifically requested by American oil baron Rand Magnus, who sought to buy it at auction for his son. Before the animal could be auctioned off, however, the operation was disrupted and the remaining dinosaurs were released into the surrounding woodland by Maisie Lockwood to save them from hydrogen cyanide poisoning. The trike, its mother, and the other two adults were last seen near Orick; their present whereabouts are unknown.

Cute baby Triceratops do seem like interesting pets, and so to very impulsive people with no foresight they are alluring. This means that there is demand for this animal on the modern black market. The auction in 2018 allowed Triceratops DNA out into the world via a Russian buyer, possibly the mobster Anton Orlov, and today it can be purchased from any number of shady sellers. Live specimens might be harder to catch, but for the right price, that is also possible. In the modern day, one of the biggest and most infamous places to find de-extinction assets is the Amber Clave market in Malta. This animal is actively bred in captivity outside the scope of the law and is trafficked around the world; wild populations in new places may be the result of captive specimens escaping or being released. In the late winter of 2022, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service shut down the Saw Ridge Cattle Company in Nevada for illegally breeding ceratopsians including Triceratops. The rescued animals were transported to BioSyn Valley. A juvenile was rescued by the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife from a poacher camp on May 17 and moved to a secure facility for treatment; its eventual home has not been released. With captive breeding and trafficking prevalent around the world, the total number of Triceratops in circulation may never be fully known.

Wild populations

Among the most common dinosaurs of North America, the Triceratops first appears in the fossil record in the late Cretaceous period about 67 million years ago. While it does not seem to have formed massive herds like some dinosaurs, it was abundant all throughout North America; due to the low levels of fossilization in the east, most of its remains are discovered in the western part of the continent. It would have inhabited floodplains and forests, avoiding wetlands as it was a poor swimmer. At the end of the Cretaceous period, close to 66 million years ago, a mass extinction event took place which killed off nearly all of the world’s megafauna. Triceratops was among the casualties, becoming extinct. Over sixty-five million years later it was reincarnated by scientific endeavors using ancient samples of its DNA, enabling it to take on a new genetically-modified form and walk the Earth once again.

On June 24, 2018, Triceratops returned to western North America after an absence of sixty-six million years. Four adults and a juvenile were released into the wild that night after a semi-successful attempt at a black market auction was foiled halfway through; no trike specimens seem to have been sold but their DNA entered the global stage. The released animals fled into the woodlands near Orick in Northern California. One adult was sighted on its own in July 2018 on a rural Californian road near Folsom, suggesting that the animals still inhabited that general area. Sightings as of early 2022 were concentrated in the southern part of California, though in the previous year the CIA had been tracking a population near the Rio Grande in New Mexico. A small group of Triceratops is depicted living in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona in Jurassic World Evolution 2; they were being monitored by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In the course of the game, three of these animals are captured from a watering hole and monitored by the USFWS. Another herd is depicted in the North Cascades of Washington State, near an abandoned poacher camp. A third herd can be seen living in the wild in Yosemite National Park, California after migrating there.

North America still has nearly all sightings, but a small herd was apparently transplanted to the British Isles by human intervention. Two adults were seen on a rural road in County Mayo, Ireland that year; since there is no overland route for the animals to have gotten here, they were probably introduced via illegal breeding or animal trafficking. The CIA’s dinosaur tracking division has also reported a population in the Harz Mountains of Germany, and near the Volga River in Russia. Farther south, they are known in the forest steppes of the southern Zagros Mountains in Iran, and from the Narmada River in India.

One African population has been identified in Ethiopia, specifically within the Great Rift Valley near the Bale Mountains. According to the CIA, the most isolated Triceratops populations currently are in Australia, living near the Murray River in the southeastern part of the country.

Behavior and Ecology

Activity Patterns

Triceratops are diurnal, and can be seen during most times of the day. They usually wake up with the sunrise, moving to areas where rocks or metal structures provide them with a means to warm themselves in the sun. They are commonly seen basking on the shores of lakes or rivers during the morning. Activity throughout the daytime consists of bathing, feeding, and social interaction. During the noontime heat, they may rest in the shade of trees. In Jurassic World, their main meals were given close to sunset. At night they usually rest, though some of the adult animals in herds may remain awake to watch for predators.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Triceratops is a selective feeder, with a mouth specialized for particular kinds of plants. It is a herbivore that eats large quantities of fibrous plants, with the bulk of its diet consisting of ferns, cycads, and palms. Their beaked mouths are designed to crop off pieces of these tough plant items, which would then be sheared apart by hundreds of teeth. It cannot chew its food, instead moving its jaw in an up-and-down motion.

Its head is built low to the ground, so it mostly eats low-growing plants. However, its bulky body allows it to push over small and medium-sized trees to get at their leaves and shoots. They are known to feed on the stalks of banana leaves (Musa callimusa), though they do not seem to prefer the blade part of the leaf. Bracken ferns grow in its habitat, and may cause health issues if consumed in excess. Soft plants are generally avoided; they do not eat West Indian lilac (Melia azedarach), which is toxic to them, or flowers in the genus Heliconia. Like many animals, they can show individual personal preference for certain types of food; for example, the individual Lovelace favored strawberries.

According to Darius Bowman, epiphytic ferns are an important part of the diet of this dinosaur due to the inclusion of neochrome. This suggests that InGen bred prehistoric ferns to feed the Triceratops. Neochrome is a photoreceptor that aids fern species in the orders Polypodiales and Cyatheales, which existed during the Cretaceous and persist today, to better perform photosynthesis in low-light conditions such as the shade of forests. What benefit Triceratops gains from neochrome is thus far unclear.

In Jurassic World: Evolution, this animal’s preferred food source is horsetails, but it will also feed on rotten wood and palm leaves. It is unhealthy for it to eat pawpaws, mosses, and cycads; this contrasts with other sources which state that Triceratops does eat cycads. The game is in error here. In its sequel, Triceratops are shown to feed on fibrous ground cover.

Social Behavior

Both loner and herd-dwelling Triceratops have been documented; fossil evidence suggests that solitary behavior or small groups would be naturally common. However, herding behavior has been observed on several occasions in InGen specimens. Herds consist of several adults and their offspring; typically, the herd is led by a matriarch, the eldest female in the group. The matriarch, as well as any other healthy adults, will fiercely defend the younger members of the herd from threats, even at great personal risk.

While Triceratops can live happily by itself, social bonds are incredibly strong among these animals; they can recognize individual members of their herds, probably by looking at unique features of their faces and color patterns. When facing one another, the frills of Triceratops make stunning visual displays that can be used to communicate or recognize each other. Larger frills provide the animals with better protection against both rivals and predators, so the animals with the largest, strongest frills become the leaders of the herd.

Dominance is achieved in this species with shows of force. A challenge is initiated by aiming the horns at the opponent and pawing the ground; the animals will then charge each other, locking horns and pushing against one another. The weaker trike will back down, establishing the stronger one as the dominant animal. Adults have been known to perform dominance displays against juveniles, situations which are probably less serious than two adults competing for dominance. These adult-juvenile contests reestablish the adults as respectable authority figures that can protect the smaller juveniles, as well as giving the juveniles practice for the combats they will face as adults. Less serious fights are also depicted in Jurassic World: Evolution 2, in which the animals may engage in playful jousting rather than violent fights if dominance in the herd is not being questioned. Such play behavior helps them to keep their skills strong.

Protective behavior in mature Triceratops does not only involve their own offspring. Adult trikes are commonly known to adopt juveniles with no genetic relation to themselves, caring for them as though they were their own. These adoptive parental relationships persist throughout life, with older adults still protecting and providing care for younger animals that have entered adolescence.

Reproduction

If the account in Prey is to be believed, Triceratops eggs hatch sometime late in the year, during what in Central America would be the rainy season. Larger dinosaurs like trikes have incubation periods that last six months to a year, but the exact duration of time that trike eggs incubate for has not been given. At least one nest has been recorded in 2016 containing five eggs, but adults are often seen with only one offspring, suggesting a high infant mortality rate.

Triceratops hatches from eggs roughly the size and shape of canteloupes, and is itself about the size of a softball as a hatchling. Rearing and protecting the young is the responsibility of all the adults, who will defend them against any threat: InGen animal behaviorist Owen Grady claims that adults will sacrifice their lives for the juveniles. Each juvenile will form a particularly close bond with one adult, though; this is often its parent, but orphaned or abandoned young are often adopted by unrelated adults. The parent, whether it is biological or a surrogate, will teach the young what it needs to know to survive and keep a watchful eye on it at all times. Youthful trikes are often carefree and unafraid of danger until they learn better; without adults around, a juvenile would be easy prey for many predators. InGen animal caretakers discovered in 2004 that embryonic and hatchling trikes respond positively to jazz music, the leading hypothesis being that the rhythm of this particular genre mimics the heartbeat of a nearby adult. This suggests that the parent-child bond starts before the baby has even hatched, and that the presence of adults provides for emotional needs as well as physical protection. Even adolescents sometimes need the comforting presence of their parental figures and other adults when they become stressed or threatened.

Courtship among the adults involves the use of the horns and frill as display structures. If Dr. Sorkin’s research into toromorphs is accurate, the rare development of the toromorph stage may be a yet-unknown display mechanism, elongating the horns and frill to make the animal appear more attractive to potential mates. The size of these features directly relates to the trike’s ability to defend itself and its family, so longer horns and a bigger frill make for a more desirable mate. Like most dinosaurs, Triceratops has a cloaca rather than external genitals, and this is used in mating.

Males will lock horns with each other when competing for mating rights. These fights show their strength, demonstrating that they can successfully fight off predators. Areas within Triceratops territory will commonly have roughly circular clearings among the bushes and shrubs, signs of males battling one another during the breeding season.

Communication

This animal primarily communicates with expressive snorting and grunting sounds, and may make trilling noises to comfort stressed younger animals. When angered or frightened, they will emit high-pitched bellows. In adults, this noise can be used to intimidate predators and alert other trikes to the danger; when used by juveniles, it is an alarm cry which draws the attention of its caregivers. This bellowing sound is also made by Stegosaurus and Parasaurolophus when they are stressed or angry, suggesting that the behavior may be convergent.

Not all communication in Triceratops is vocal. Body language plays a major role in their dialogue, with stomping and head-tossing being some of the main ways they communicate. Stomping the feet is used to show excitement; on the other hand, pawing at the ground is a clear threat display, made more serious if the horns are aimed at the target. Trikes will toss their heads when they are agitated, and the frill makes this a very obvious motion to other animals. This makes head-tossing an easy non-vocal way to let other herd members know that something is amiss. Shaking the body and swishing the tail are signs of nervousness.

Physical contact is also used by adults to comfort juveniles and adolescents. A mother may nuzzle her offspring using her snout, or they may place their frills together and rub them against one another. The back of the frill is a sensitive area which the Triceratops enjoys having rubbed.

Ecological Interactions

This solidly-built herbivore has few predators, and itself maintains the grassy plains it inhabits by regularly cropping brush and pushing over trees. It does not eat much fruit, so it is not a major distributor of seeds. Instead, it preys on the stems and leaves of certain plants, such as bananas, preventing them from growing and spreading. However, some plants such as West Indian lilac and bracken may have adverse health effects on trikes that consume them. As it feeds, its habitat will turn to scrubby grassland. It produces large quantities of dung, often regularly using the same location to defecate. Its dung can fertilize the ground, and also attracts insects, which in turn attract small predators.

As an adult, the horns of the Triceratops make formiddable weapons against even very large predators and its frill protects its neck from being bitten. It is sometimes preyed upon by Tyrannosaurus rex, a predator-prey relationship that extends all the way back to the late Cretaceous period. However, an adult trike can drive away a tyrannosaur using its horns. The juveniles are less capable of protecting themselves, relying on adults for safety from predators including Velociraptors and particularly ambitious Pteranodons. Larger theropods such as Allosaurus and Teratophoneus may also pose threats to juveniles, and the adults will defend them vigorously. Triceratops has been known to live in territories inhabited by the tiny Compsognathus, which probably does not present a major threat, as well as the medium-sized theropods Carnotaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Baryonyx. According to the Jurassic World Employee Handbook penned by Claire Dearing, Carnotaurus will sometimes attempt to prey on Triceratops. The giant Spinosaurus has also been reported from areas where trikes live, but this animal usually hunts in or near deep bodies of water. The omnivorous Gallimimus can on occasion be found in trike territories, but aside from perhaps eating their eggs, it would not pose them any threat.

Triceratops can coexist with a fair number of other animals, and can be seen living in close proximity to other herbivores. It avoids competition through its aggressive territoriality, driving away weaker competitors. Nonetheless, it has been witnessed in the wild living peacefully alongside fellow armored herbivores Ankylosaurus and Stegosaurus. These dinosaurs feed on different food sources and prefer more densely forested areas, so they can coexist with Triceratops without too much difficulty (though an aggressive conflict between a Triceratops and an Ankylosaurus was witnessed in California in mid-2018). Sauropods, such as Brachiosaurus, Mamenchisaurus, and Apatosaurus, avoid competing with it by feeding on higher trees. Its main conflicts, then, take place between it and less well-defended herbivores such as Pachycephalosaurus, Stygimoloch, Parasaurolophus, and Corythosaurus. It was known to inhabit the same territory as fellow ceratopsid Sinoceratops and possibly Pachyrhinosaurus, though the relationships between them are not well known. Trikes are known to be aggressive toward the young of other species, sometimes harassing them to the point of death; this would make them a force of natural selection in their environments.

However, the presence of these powerful herbivores is beneficial to the small animals they do not directly compete with. They are often seen alongside many species of birds, including the collared aracari, which benefit because the trikes keep medium-sized and large predators away. Some birds are known to perch on top of resting trikes, possibly picking off parasites such as ticks as well as eating dead skin. Small non-avian dinosaurs, too, would do better living near trikes, so long as they avoid competing with them for food. The minute Compsognathus and Microceratus have been known to live near or within Triceratops habitats.

The game Jurassic Park: Operation Genesis states that it prefers to keep company with Torosaurus, which has been suggested to be a rare growth stage of Triceratops. Aside from a single reported toromorph in the late 1980s or early 1990s, no members of this genus (or trikes which reach this proposed growth stage) have been observed in the film canon.

Like all dinosaurs, the Triceratops is host to many microorganisms and parasites. It bathes in water regularly to avoid infections such as bumblefoot, which is caused when bacteria invade a cut or scrape on the foot.

In the game Jurassic World: Evolution, this dinosaur is particularly susceptible to parasitic hookworms, but is not known to host the bacterium Campylobacter and is therefore immune to campylobacteriosis.

Cultural Significance

Symbolism

This is one of the most famous of all dinosaurs by a large margin, and as one of the more common Cretaceous species found in North America, major discoveries are often a source of pride for towns and states where this dinosaur’s fossils are uncovered. Often compared to the American bison, which now lives in the same region, Triceratops is associated with similar personality traits such as stubbornness, confidence, and loyalty. Many people mistakenly believe that herbivorous animals are friendly and harmless; Triceratops is assuredly not so, and is often offered as a rebuttal when this misconception is applied to dinosaurs. Artwork frequently depicts it in combat with Tyrannosaurus rex, and while real life is not always so dramatic, there is evidence that Tyrannosaurus did hunt Triceratops. The latter certainly could have defended itself using its large horns. Thanks to the abundant fossils found of this dinosaur and its astounding defensive weaponry, it is one of the mainstays of dinosaur media, making appearances in comics, film, video games, and books of all sorts.

Some of the logos used by the Dinosaur Protection Group feature Triceratops, including one with the animal’s frill stylized to resemble a heart icon. This dinosaur’s reputation for being protective worked well for the DPG, whose mission of course is to provide for the welfare of de-extinct animals.

Triceratops horridus is the state fossil of South Dakota, and the state dinosaur of Wyoming since 1994.

According to Universal Studios, Triceratops is the dinosaur of the Capricorn astrological sign (December 22 – January 19).

In Captivity

Because of its famous nature as the best-studied ceratopsid, and one of the largest, this dinosaur has been featured in many de-extinction attractions. InGen’s original plans for Jurassic Park on Isla Nublar would have had two different trike paddocks, making it visible from both the main tour and the Jungle River Cruise. Adults and juveniles were both to be exhibited, showcasing the buffalo-like herding behavior and dominance displays put on by this popular dinosaur. The attempt at resurrecting Jurassic Park: San Diego planned to feature a father and child Triceratops, though this did not succeed.

Jurassic World housed at least two herds of Triceratops, placing adults in both the Gyrosphere area of the central valley and an attraction called Triceratops Territory. Juveniles, like those of most of the herbivores, were kept in the Gentle Giants Petting Zoo; here, children were permitted to ride on the dinosaurs using specially-made saddles, and visitors could feed them cubes of dinosaur food for US $5 a piece. Visitors were encouraged to rub them behind their frills, which helped them become comfortable with the children riding them. Triceratops was unequivocally one of the most popular and beloved attractions in Jurassic World.

However, exhibiting this dinosaur is not without quite a bit of difficulty. Its diet is restrictive, as it does not generally eat soft plants and must be fed tougher, fibrous food. Finding a suitable habitat to raise it means ensuring that the plants it needs can grow there. Secondly, while this animal is only dangerous when provoked, it is very dangerous when provoked; its horns can cause serious damage to vehicles and other equipment, and its enormous bulk can easily crush and kill a human in seconds. Adults guarding young are particularly easy to provoke, which makes it difficult to exhibit both adults and young to the public safely. Jurassic World got around this challenge by separating the young from the adults until adolescence was reached. Even then, the young adolescents could cause disruption by engaging in dominance displays with each other while visitors were trying to interact with them; Jurassic World’s Asset Containment Unit had tranquilized young trikes when this behavior occurred on multiple occasions.

Once in their habitats, Triceratops could still cause problems. While its feeding behavior helps with upkeep of plant life, it may be problematic toward other dinosaurs. Though it is not always aggressive, it can be hot-headed, and it may bully weaker animals that compete with it for food. This was an issue in Jurassic World’s early stages of development, as the hatchling Ankylosaurus could not be safely introduced to the central valley due to the trikes’ aggressively competitive nature.

Other minor problems involving Triceratops were the tendency of juveniles to eat human food if given the opportunity, which could be unhealthy for them, as well as food-like items such as straw hats that visitors might be carrying. They could become nervous around unfamiliar people, increasing the chances of aggressive behavior. Small injuries sustained during intraspecific combat would also be health concerns for InGen’s paleovets, as they could become infected and lead to more serious pathology.

Despite all this, Triceratops is among the most commercially successful of InGen’s dinosaurs. It has consistently featured in every attempt at a de-extinction park, and the juveniles are adored by animal enthusiasts the world over. Even to their handlers, this dinosaur was often enjoyable to work with due to its social nature. Not only can they recognize specific members of their own species, there is some evidence that they can recognize human faces; they are known to be more comfortable when they work with the same caretakers, which InGen discovered as early as 1993. According to the Jurassic World Employee Handbook, Triceratops was the second-most visited animal asset in the park, exceeded only by Tyrannosaurus rex.

Science

This is one of the best-known dinosaurs due to its fossils being quite common, as well as being one of the more charismatic American dinosaurs and thus a surefire way to gain funding. Its fossils are frequently used as museum displays, often alongside those of Tyrannosaurus. The predator-prey relationship of these two dinosaurs is established scientific fact, and is probably one of the most famous examples of prehistoric ecology. Since so many fossils of Triceratops have been found, its biology is quite well understood, more so than many long-extinct organisms. It provides valuable information about ceratopsid evolution in North America, as well as the ecosystem of its time.

Its ontogeny has long been a matter of some debate. Some paleontologists throughout history have suggested that Torosaurus, a genus of large ceratopsid found in areas near Triceratops, was not a different creature at all but actually a rarely-seen mature form of Triceratops. News outlets have periodically wrongly reported Triceratops to be an invalid name, whereas in reality if the two were found to be synonymous Triceratops would become the name for both (as it was designated first). Many paleontologists disagree that Triceratops and Torosaurus were different growth stages for one animal, though. First among the rebuttals is that they did not live at quite the same time. Additionally, Torosaurus skulls have large fenestrae, while Triceratops skulls are completely solid.

Triceratops is notable in the history of de-extinction for being the first species ever resurrected. It was created through genome editing by Dr. Henry Wu after the successful 1984 extraction of Cretaceous-aged ancient DNA from amber by Dr. Laura Sorkin, and then implanted into an unfertilized ratite egg. It hatched on Isla Sorna, Costa Rica in 1986.(Note: in reality, the first de-extinct animal was the Pyrenean ibex, which was born on July 30, 2003. The clone did not survive.) Since its de-extinction, Triceratops has yielded plenty of genetic data about its ancestor, though the genome editing inherent in Wu’s process meant that it was distinctly different from the original animal. This makes its usefulness to paleontology limited, but information about the original can still be extrapolated from the de-extinct version.

InGen research uncovered much about its social structure and reproductive cycle from the 1980s onward, though aspects of its ontogeny still remain mysterious. Most interestingly, Dr. Sorkin’s notes from the early 1990s make mention of a mature “toromorph” developing, suggesting that Torosaurus may be a synonym of Triceratops, but no similar observations have been made since. As a matter of fact, later sources have confirmed the two are separate genera. More information will hopefully come with time. One unexpected fact discovered by InGen in 2004 is that young trikes become relaxed by listening to jazz music; it is hypothesized that the beat of the songs mimics the heartbeat of a protective adult. This effect is even observed in unhatched embryos as soon as they are capable of hearing, providing new insight into the parental behaviors of this dinosaur.

As the first confirmed addition to InGen’s genetic library, Triceratops has had probably the most research put into its genome and was fully sequenced sometime before 2015. Having all of its genes identified allowed scientists such as Dr. Wu to analyze it for the genes linked to particular physiological traits, making it easy to use Triceratops for further research. One groundbreaking field of science that has utilized this dinosaur is artificial hybridogenesis, which has yielded Stegoceratops through splicing Triceratops genes into the Stegosaurus genome.

Politics

In early 2017, Isla Nublar’s volcano Mount Sibo became active, gradually building up toward an explosive eruption that would devastate the island ecosystem. Among the other dinosaurs, Triceratops became threatened with extinction. Debate persisted for over a year regarding how to respond. The island was still under lease to Masrani Global Corporation, but the company cited costs as their justification for ignoring the events. Under a conservative anti-environmental government, the United States Congress also took no action. Their justification was that Isla Nublar was leased to Masrani Global for private development, and therefore outside U.S. jurisdiction, but no effort was made to hide the real motive behind their non-action policy. Costa Rica, likewise, took no official actions.

In early 2017, Isla Nublar’s volcano Mount Sibo became active, gradually building up toward an explosive eruption that would devastate the island ecosystem. Among the other dinosaurs, Triceratops became threatened with extinction. Debate persisted for over a year regarding how to respond. The island was still under lease to Masrani Global Corporation, but the company cited costs as their justification for ignoring the events. Under a conservative anti-environmental government, the United States Congress also took no action. Their justification was that Isla Nublar was leased to Masrani Global for private development, and therefore outside U.S. jurisdiction, but no effort was made to hide the real motive behind their non-action policy. Costa Rica, likewise, took no official actions.

This is not to say that public opinion was against the animals’ survival; the most notable force pushing to have them rescued was the Dinosaur Protection Group, founded and headed by Jurassic World’s former Operations Manager Claire Dearing. Under her guidance, the DPG spent 2017 and early 2018 lobbying to have the dinosaurs relocated to a safe haven. Triceratops, as one of the most famous and beloved dinosaurs, featured heavily in DPG outreach and publicity pieces. Despite all this, the world failed to mount a rescue mission. Instead, the Lockwood Foundation intervened, with its founder Benjamin Lockwood (a close business partner of Hammond’s, and an InGen founder) hoping to save the dinosaurs by moving them to Sanctuary Island. This operation was carried out in June 2018 without the knowledge of the United States or any other governing body.

The mission was overseen by the Lockwood Foundation’s manager Eli Mills, who hired mercenary hunter Ken Wheatley to round up the dinosaurs. A few Triceratops were among those captured. Rather than relocate them as planned, Mills had Wheatley move the captured animals to Orick, California where they were sold on the black market at the Lockwood estate without his employer’s knowledge. A baby trike had specifically been requested by Texan oil baron Rand Mangus, who wanted to buy the animal as a pet for his son. It is unknown if any live Triceratops were sold (the baby was not, nor was its mother), but a case of DNA samples including this species were purchased by a Russian buyer (most likely Anton Orlov). The remaining trikes were released into the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Resources

Triceratops is one of the most tremendously famous dinosaurs and is sure to bring tourists flocking to see it. At Jurassic World, this was one of the original eight species present; InGen had previously tried to feature it in Jurassic Park, though this attraction never opened despite two failed attempts. Once it finally succeeded, Triceratops proved to be one of the biggest draws to the park. With many places to see these creatures, they were second only to Tyrannosaurus in terms of bringing ticket sales. Adult trikes could be seen at attractions in the park’s valley region, and juveniles were the most popular part of the Gentle Giants Petting Zoo. Here, tourists could feed them, and younger children could ride on them under the careful supervision of park employees. Of course, keeping Triceratops is not cheap, since they grow to huge sizes and require large amounts of food and territory. They can also cause problems with their aggressive behavior and require frequent maintenance to be kept under control.

Along with its potential as an attraction, Triceratops is valuable to medicine. While this may be unexpected, it makes more sense when one considers how long it has been extinct. Its closest relatives are the birds, which are somewhat evolutionarily removed from ceratopsians. Because of this, Triceratops has biochemistry unlike any modern animals, and it may yield biopharmaceutical products that cannot be obtained from modern life forms. Since it has been genetically engineered, its properties may be altered from its ancestor as well. Though little research has gone into using Triceratops for medical purposes, its value on the black market cannot be understated. In 2018, American financier Eli Mills employed hunter Ken Wheatley to capture several Triceratops, including a mother and child; the juvenile was specifically intended to be sold to Texan oil magnate Rand Mangus. Horse buyers employed by Mangus were sent to bid on the juvenile, which Mangus had wanted to get as a pet for his son. Having a pet Triceratops may be tempting while the animals are young and manageable, but the adults are much too large for domestic life.

The adults would presumably have had immense value as well, and were expected to sell for millions of U.S. dollars. Their purpose is not yet known; they may have been destined for pharmaceutical research, or they may have been sold for exotic animal parts similar to the sad fates of many rhinoceros and elephants. Whatever the case, all of the known live specimens escaped into the wild when the auction was disrupted. A case of twelve pairs of DNA samples, including one pair from Triceratops, was sold to a Russian bidder. This is assumed to be Anton Orlov, since the case was sold to the same buyer as a live Baryonyx and Orlov had been interested in purchasing large theropods.

Safety

Triceratops is big, aggressive, and unwilling to back down from a fight. It is certainly one of the more dangerous dinosaurs to interact with, as its temperament may change from docile to raging without a moment’s notice. If you encounter this animal in the wild, it is better to give it a wide berth, rather than try to “bond” with it as you may have seen at Jurassic World. While it might seem like captive Triceratops are friendly, the reality is that their keepers have had years of experience and know how to be safe around these potentially deadly dinosaurs. Wild Triceratops are even more dangerous, since they need to be ready to defend themselves against predators. Large females are probably the most risky, since their job is to protect the younger animals, but the males are not pushovers by any means. Just keep your distance from any Triceratops you see. Juveniles are not usually aggressive, but they seldom stray far from the adults. Do not feed, pet, or try to ride on this dinosaur or any wild animal.

Now that these dinosaurs have gradually integrated into our world, an encounter is more likely. Fortunately for us, Triceratops mainly prefers open land, so you will easily see it coming and have time to get out of the way. If you are in a vehicle, do not assume you are safe: these animals are highly territorial and may mistake your vehicle for a competing herbivore due to its shape. Either shut down your engine or drive away from the Triceratops, do not approach, and do not honk your horn at it to get it to move. It can easily roll or crush a vehicle with its horns and bulky body, almost certainly killing you in the process. You can try to deter attacks by painting diagonal red stripes on your vehicle, as this seems to cause most ceratopsians to deem vehicles non-threatening. Some retailers in areas where ceratopsians live have also begun selling magnetic “Trike-Stripes” which serve the same purpose. Encountering it outside of a vehicle can actually be safer, since you are more agile this way and are less likely to appear like a threat. Make sure you stay that way by respecting its space, not making sudden moves, and staying in its line of sight. If you go around behind it, the dinosaur might think you are trying to ambush it. Stay where it can see you and do not surprise it. This species has poor vision and is easily startled by unexpected movement.

Even following all these guidelines might not always prevent an attack, but you can predict when it is going to charge. It will usually paw the ground and shake its horns back and forth, demonstrating its size and readiness to go on the offensive. This warning display is meant to intimidate predators. Back away quickly and quietly if you see these movements, and get ready to dodge. Its attack strategy is fairly limited: it will charge you head-on, aiming to crush you. Since you are fairly small, its horns are not going to be its primary weapons; these are for combat with other Triceratops and to defend against large predators. Foes your size are more easily trampled than impaled. If you feel it gaining on you, quickly dodge to the side. It is not as nimble as you are and will take a moment to reorient itself. Use this moment to find a place to hide, such as up a tree, in a narrow crevice, or inside a very sturdy building. Water is also a good escape route, since all ceratopsians are poor swimmers. If escape is impossible, try hiding in tall grass, or lying flat and playing dead.

Since Triceratops is an herbivore, it will not attack to try and eat you. Instead, it will most likely attack because it thinks you are a dangerous predator threatening its family or itself. To avoid this misunderstanding, avoid walking in between mother trikes and their offspring, or between any other trikes you see together. Do not try to intimidate them: this dinosaur routinely stands up to Tyrannosaurus rex. You are not more intimidating than a Tyrannosaurus rex, so your efforts will be in vain. For the most part, you will be safe from Triceratops if you simply keep your distance and pay attention to their body language. In the event that they do attack, making evasive maneuvers will save your life; if you get out of sight, they will eventually decide that you are no longer threatening, and will leave you alone.

Notable Individuals

Lady Margaret – alpha female in Jurassic Park; deceased in 1993

Sick Triceratops – female bred for Jurassic Park, possibly called “Freda” or “Sarah”

Bakhita – female bred for Jurassic Park

Hypatia – eldest female ever kept in Jurassic World

Curie – female housed in Jurassic World

Johnson – female housed in Jurassic World

Lovelace – youngest female in Jurassic World as of 2004

Disambiguation Links

Triceratops serratus (*) (C/N)