Jurassic Park: San Diego was a planned de-extinction theme park located in San Diego, California, owned and operated by International Genetic Technologies, Inc. It was constructed between 1983 and 1985, with a brief revival of construction in 1997 before being completely abandoned.

Had the Park opened, it would have exhibited de-extinct life forms to the public for the first time in history. It was abandoned in favor of the more grandiose Isla Nublar location in 1985, which was constructed between 1987 and 1993 before also being abandoned. After the infamous 1997 San Diego incident, InGen was bought out by Masrani Global Corporation, and construction on Isla Nublar resumed under the name Jurassic World.

Name

Before the Isla Nublar location was conceived, this attraction was simply called Jurassic Park, and may have continued to go under that name had it opened in 1997 as planned. InGen at that time likely wanted to keep the Isla Nublar park under wraps to avoid bad press, and the name “Jurassic Park: San Diego” was probably only used internally. The name references the Jurassic period, the middle period of the Mesozoic era. Despite this name, Jurassic Park would have exhibited animals and plants from throughout the Mesozoic, not only the Jurassic period.

Had other Jurassic Park locations opened as InGen had planned during the early 1990s, clarifying the San Diego locale would have been more relevant. However, as of this point in time, no two de-extinction theme parks have ever been open simultaneously.

Location

Jurassic Park: San Diego was built on InGen property in San Diego, California near its waterfront complex. The location was chosen for its proximity to other InGen facilities, such as its headquarters and harbor, as well as San Diego’s reputation for animal attractions including SeaWorld and the San Diego Zoo. With the waterfront not far away, animals inbound from Site B would have not had far to travel overland from the harbor to their new homes.

Description

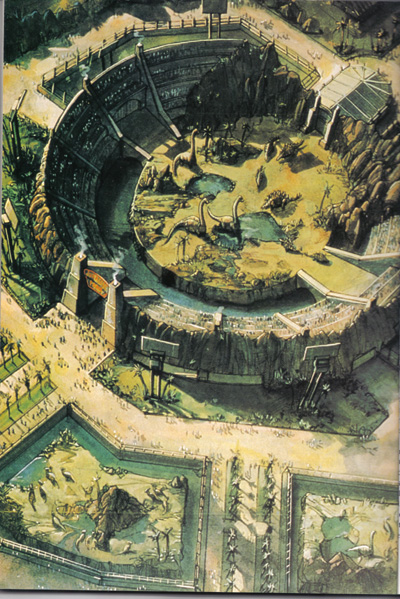

The centerpiece of this modestly-sized zoo was a large amphitheater, which took up a large amount of park area. This had a central location and was modeled from the outside to resemble a ring of mountains or the jagged crater of a volcano. Inside, it would have had seating for hundreds of people to view animals as they were brought into the amphitheater for display, possibly with different shows occurring throughout operating hours. Opposite the visitor entrance was a set of gates leading to the control center, which would also have housed an infirmary and veterinary clinic.

While the facility was still under construction at the time it was abandoned, concept art and other sources give some idea of how it would have looked when it opened. The main entrance to the amphitheater would have been a set of huge wooden gates decorated with torches, similar to the Jurassic Park entrance gates used on Isla Nublar. Two north-south lanes coming to and from the Park’s entrance would have led to these gates, enabling incoming and outgoing traffic to flow simultaneously. At least six animal paddocks, aside from the amphitheater, were planned; four appear to have been located to the south of the amphitheater, while two were adjacent to its northeast and northwest sides. No animals were ever introduced to them, but they would have been built to accommodate whichever species was decided to populate these paddocks. Since they were fairly small in size, they would have been more manageable than the vast wilderness areas designated to the animals in the Isla Nublar facility, and could have been personalized more easily. This also would have given one hundred percent visibility to visitors, rather than leaving large tracts of land mostly unobserved.

To the north of the amphitheater were sites where visitor facilities, such as restaurants and retail outlets, could be constructed; these would probably have consisted of both InGen brands and partnered companies. Bathrooms were probably present near these facilities. Security and maintenance staff would probably have been headquartered near here. Access to the marina appears to have been to the northwest of the Park. To the south, the main entrance led into the parking lot, which was connected directly to the streets of San Diego. As of 1997, a security checkpoint existed to ensure only authorized personnel could enter the facility, but this would probably have been replaced with more standard entrance gates when the Park opened.

History

1975-1985: Initial construction

International Genetic Technologies was founded in 1975 by Dr. John Parker Hammond and Sir Benjamin Lockwood in San Diego, California. One of the company’s most lofty goals was de-extinction, or the practice of returning extinct species to life. Hammond’s dream in particular was to bring about the de-extinction of Mesozoic reptiles including dinosaurs, which was thought impossible at the time. Despite this, he believed that there was a way to achieve it, and research in the early 1980s was conducted at the Lockwood estate.

In 1982, InGen took out a 99-year lease on the East Pacific island of Isla Sorna from the Costa Rican government for purposes of research, and the neighboring islands of the Muertes Archipelago were included. The following year, construction began on Jurassic Park in San Diego, establishing it on property near the InGen waterfront. Plans were to reconstruct the genomes of ancient life forms from fossils such as amber, clone the results at the Site B facility on Isla Sorna, and ship them north to the marina near the Park for exhibition.

InGen had its first successes with de-extinction in 1984, with the first test fertilization of an artificial ovum. This technology would make cloning dinosaurs possible. The next year, InGen geneticists demonstrated that viable ancient DNA could be extracted from samples preserved in amber, and that this mode of preservation had the potential to extend the lifespan of the DNA molecules hundreds of times over. With this research complete, de-extinction of Mesozoic life could become a reality.

1985-1997: Abandonment

Hammond opted to relocate the Park in 1985, the same year aDNA was first extracted from amber. InGen entered into more talks with Costa Rica, eventually agreeing to add the island of Isla Nublar into their preexisting land lease. Not all of InGen agreed with this decision; for example, Peter Ludlow believed that San Diego was more accessible and affordable than an island facility. Hammond’s choice seems to have been based in the idea that the mysterious allure of a remote island would create an ideal atmosphere for his vision, but it would also have added security that a facility based in San Diego would not. A new version of the Park came under construction on Isla Nublar in 1987 after two years of preliminary planning and relocation of the indigenous people. The San Diego facility, despite being nearly complete, was abandoned.

InGen had by the early 1990s returned many species of animals and plants from the Mesozoic to life, much of it made possible by the revolutionary genetic engineering techniques pioneered by Dr. Henry Wu. Unfortunately, the Park was not able to open successfully. Financial issues came with Lockwood leaving the company sometime in the 1990s, and InGen was impacted by corporate espionage perpetrated by its rival BioSyn Genetics. Jurassic Park’s lead programmer, Dennis Nedry, was bribed in 1993 by BioSyn’s Lewis Dodgson to steal dinosaur embryos from cold storage, and to accomplish this Nedry sabotaged the Park. His plan failed, and his death during the ensuing incident meant that power could not be fully restored until irreversible damage had been done.

Jurassic Park’s existence was revealed to the public by Dr. Ian Malcolm, a special guest who had witnessed the incident and discussed it in a 1995 television interview. His claims were met with extreme skepticism, though some people did believe he was telling the truth; the existence of the Jurassic Park amphitheater would have been evidence in his favor, but this was kept restricted property by InGen, so it would not have been publicly accessible. Peter Ludlow perpetrated a smear campaign against Dr. Malcolm to discredit him; most people considered him a fraud and his claims a hoax. Hammond took little public action, having vowed to end the Jurassic Park project and keep the dinosaurs safely alive in private isolation on Isla Sorna. His decision was met with resistance from the rest of InGen, and after a string of lawsuits and safety incidents between 1993 and 1996, the Board of Directors fired him. Ludlow assumed the position of CEO when the process was finalized.

1997: Attempted revival

1997 saw Ludlow enact plans to retrieve animal assets from Isla Sorna now that Hammond no longer had the authority to stop him, bringing them to San Diego for exhibition in the original Park. He assembled a team of experts to round up dinosaurs and transport them. At that point, Jurassic Park: San Diego was about a month away from being able to receive guests; Ludlow already had publicity stunts ready, though he continued to suppress information about the Park in order to make its grand reveal more of a shock and draw media attention. Hammond, on the other hand, sought to stop Ludlow even though he no longer had authority at InGen. His countermove was to send a small ground team to document the animals in the wild, using environmentalist values to encourage the public to support keeping Isla Sorna a sanctuary. If necessary, Hammond’s team would sabotage Ludlow’s, preventing the removal of dinosaurs from the island.

The conflict on Isla Sorna led to the entirety of both parties becoming stranded on the island for over a day, and when Ludlow returned to San Diego it was with only two dinosaurs to show for it: a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex and its father. Their capture was entirely an accident, as Ludlow’s lead hunter Roland Tembo had tranquilized the adult during an attack due to his bullets being stolen by Hammond’s documentarian Nick Van Owen. The juvenile was retrieved from its nest by InGen personnel to accompany its father as a park exhibit. Ludlow flew the juvenile to San Diego by jet, storing it in the Park’s command center and veterinary clinic with security guards posted to watch it. Meanwhile, he met the press at the InGen harbor, where the transport vessel S.S. Venture was set to deliver the adult, giving a speech to announce Jurassic Park as the animal arrived.

Issues had arisen during transport, and the tyrannosaur had been accidentally released; this incident caused the death of the Venture‘s captain and led to the ship colliding with the harbor. The tyrannosaur was unintentionally let out of the cargo hold where crew had trapped it, and the aggravated animal caused injuries, property damage, deaths, and general chaos. The juvenile was still kept sedated in the Park facility; Dr. Malcolm, who had been involved with the events on Isla Sorna and attended Ludlow’s press conference, came to the Park with his romantic partner Dr. Sarah Harding to retrieve the juvenile. InGen staff attempted to stop them, but failed. The scientists used the juvenile to lure the adult back to the Venture and seal them inside the cargo hold. Ludlow himself pursued them in an attempt to get the juvenile back, but was killed in his efforts. Both tyrannosaurs were relocated back to Isla Sorna in the ensuing hours.

1997-present: Final abandonment

With Ludlow dead, InGen was again thrown into chaos, and de-extinction was a public fact. In the ensuing few months, Hammond passed away after helping the United States House Committee on Science write the Gene Guard Act, a piece of legislature protecting de-extinct life. InGen became available for purchase, with the primary bidders being Tatsuo Technology and Masrani Global Corporation. The winner of this bidding war was Masrani Global, headed by Hammond’s personal friend Simon Masrani; within a year, genetic research resumed illegally on Isla Sorna, but was made legal again in 2003 due to bribery between corporate and governmental entities.

InGen landed on Isla Nublar in 2002 to tame the island and rebuild Jurassic Park under a new name, rebranding it Jurassic World. Under the wing of Masrani Global, InGen capitalized on the mysterious past of Jurassic Park, which was mostly kept hidden from the public eye, but otherwise distanced itself from its own history. The San Diego facility was abandoned for good, and was probably deconstructed or repurposed. Jurassic World itself opened on May 30, 2005 and operated until its closure on December 22, 2015.

Cultural Significance

Due to the high level of secrecy around the Jurassic Park project, the San Diego facility never got the international attention that Isla Nublar and Isla Sorna have, instead being little more than a footnote in the history of de-extinction. Its location was public, but as it was on private InGen property, most people probably could not actually go see it. During the mid-1990s when conspiracy theories about Jurassic Park circulated among the general populace, the amphitheater (which blatantly read “Jurassic Park” over the entrance gates) was probably the biggest piece of evidence that Dr. Ian Malcolm‘s claims were not a hoax, but most people were unaware of the amphitheater’s existence and so continued to believe that he had concocted the story for attention.

The Jurassic Park: San Diego property was only known officially to the public on the day of the 1997 incident, when InGen’s CEO Peter Ludlow revealed it a month away from its planned opening date. Obviously, it did not open, and work on it ceased within an hour of the press conference in which it was revealed. Its only visitors were InGen employees and any city officials tasked with inspecting it. Due to the San Diego incident and Ludlow’s death, plans to open Jurassic Park were scrapped; the San Diego facility was probably never used to house animals and may have been deconstructed since 1997. Jurassic World operated on Isla Nublar from 2005 to 2015, but no references to the San Diego park have been made since. More than anything else, Jurassic Park: San Diego stood as a testament to hubris, corporate coverups, and animal rights issues.

Ecological Significance

The property upon which the Park facility was built had already been urbanized as the city of San Diego grew, so no damage to the local ecosystem would have been directly caused by its construction. During the twelve years it stood mostly abandoned, it would have provided shelter to urban wildlife, but most of these animals would have been evicted from the Park when it was reused in 1997.

Had the Park opened, it would have showcased de-extinct life to the public for the first time, and provided habitats to numerous species of dinosaur on the North American mainland. Most of the species collected in 1997 for the Park were actually known from fossils in North America, but the ecosystem had changed radically in the millions of years since they had last lived there. While the roster of species planned for the Park probably would have grown over time, some of those that InGen planned to exhibit there on opening day are known:

- Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis

- Parasaurolophus walkeri

- Gallimimus bullatus

- Stegosaurus stenops

- Compsognathus longipes

- Triceratops horridus

In addition, plans may have existed for sauropods (most likely Brachiosaurus or Mamenchisaurus) to be exhibited there based on concept art, but transporting adults of these species would have been very difficult, so InGen was most likely going to breed new ones and ship them as juveniles instead.

Although all of these species had been rounded up during the 1997 incident, none were ever actually brought to the Park due to interference from InGen’s previous CEO John Hammond. Instead, a juvenile male Tyrannosaurus rex was transported there by jet in a hasty plan to keep the Park viable. Its father was shipped overseas, the intent being to showcase both father and son alongside one another for the Park’s grand opening. This had never been a part of Ludlow’s plans; the adult and its mate had attacked Ludlow’s camp during the operation, and the male was tranquilized by his lead hunter in defense of the others. With all his other assets gone, Ludlow made the executive decision to collect the juvenile tyrannosaur and bring both to San Diego. Ultimately, only the juvenile was ever truly housed at the Park, and was retrieved by Drs. Ian Malcolm and Sarah Harding after a short time to be reunited with its parents. Both tyrannosaurs were returned to Isla Sorna around 11:30am local time.

After the events of 1997 and the subsequent Masrani Global buyout, InGen probably deconstructed the Jurassic Park: San Diego facility. It is unknown what has been done with the property since.

Behind the Scenes

Map Discussion – Original JPLegacy Transcript

This map is the result of an effort by the Jurassic Park Legacy Research staff to correct the mistakes made by the original version by Márcio Luiz Freire de Albuquerque. Originally, the map had the all too common fallacies of mixing film canon with novel canon, and has since been revised and modified for the purposes of accuracy in the Jurassic Park Encyclopedia.

Throughout the map project, we tried to remain loyal to the films whenever it came to speculation. Unfortunately, not much is known about the San Diego attraction aside from that it would feature a central arena with shows as well as security for an herbivore-oriented park. What little is known is taken from concept art.

Our speculation comes primarily from conceptual art seen in the film. Most of this speculation pertains to the placement of various paddocks as well as amenities such as restaurants, souvenir shops, and a playground, as well as the naming of these places based on known concept art.

The dinosaurs seen on this map are listed based on what InGen is known to have captured during their expedition to Isla Sorna in 1997; essentially, these are speculative projections for what InGen may have planned to include in the revitalized Jurassic Park: San Diego. Animal placement is, again, speculation based on conceptual art as seen in the film, with animal identifications made to the best of our ability. It is possible that InGen planned to capture juvenile sauropods such as Brachiosaurus or Mamenchisaurus, both of which are definitively known to exist at Site B, judging from the concept art, though this is by no means a confirmation.

The building placement and naming conventions, we admit, are the result of artistic licensing and based on some of the names from Universal’s Island of Adventure’s Jurassic Park ride. This is not an attempt to pass these off as “canon,” per se, but our attempt at identifying what the buildings could possibly have been used for, had the San Diego facility been successfully completed and opened to the public.