Isla Sorna, also called Site B or InGen‘s Lost World, is a moderately-sized volcanic island located approximately 207 miles west of Costa Rica. It is the largest and centermost island of the Muertes Archipelago, and the third island to have formed in the chain. Isla Sorna is best known for the InGen research which occurred there over a thirteen-year period between 1982 and 1995, during which time de-extinction was accomplished successfully. Between 1986 and 2004, the island was inhabited by de-extinct animal life. Official sources claimed that the island was free of de-extinct life and abandoned by May 2005, but significant evidence to the contrary exists, and these claims have been outright refuted by the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife as of 2022.

Since 1982, Isla Sorna has been leased from the Costa Rican government by International Genetic Technologies, Inc. (now a division of Masrani Global Corporation). It has been jointly controlled by InGen Security and the United Nations since late 1997, with the Costa Rican Department of Biological Preserves advising. The island has been restricted to the public since 1997, and is accessible only for governmental and corporate use by its current owners.

Name

The island’s Spanish name Isla Sorna translates to “irony island” or “sarcasm island.” All five major islands of the Muertes Archipelago bear Spanish names with negative connotations, though Isla Sorna’s name is among the milder ones. These names may have been assigned as early as 1526, when most historians agree Europeans first discovered the islands, but its exact history is unknown. Local people such as the Bribri likely have an older name for Isla Sorna, but it is not currently known.

Location

Isla Sorna is the middlemost island of the Muertes Archipelago, with Isla Muerta to the north and Isla Tacaño to the southeast. Its geographic coordinates are centered at 7°70’55.7″N, 90°00’58.2″W. GPS and other technological readout may show slightly different (one or two degrees) to extremely different (up to 168 degrees) coordinates, suggesting magnetic disturbances similar to those that occur near Isla Nublar which may interfere with navigational technology. This island is situated on the Cocos Plate in the East Pacific Ocean, about 207 miles (333 kilometers) west of the Costa Rican coast.

Description

The largest island in the Muertes Archipelago, Isla Sorna has an area of roughly 167 square miles (432.5 square kilometers). This is sometimes confused with the 22-square-mile area of the more famous Isla Nublar, which is also owned by International Genetic Technologies; in reality Isla Nublar is the smaller of the islands. It, like the other members of the archipelago, formed in prehistory from hot-spot volcanic activity on the Cocos Plate. The island’s steep mountainous peaks are largely igneous in origin, formed from ancient volcanic eruptions. Isla Sorna’s size suggests that multiple volcanoes acted to form its landmass, most of which are now extinct. Some geothermal activity continues beneath the central island, but major eruptions have not occurred in recorded history.

Isla Sorna forms an irregular pentagonal shape. It is geographically young, likely only a few million years old, and therefore its cliffs and peaks have yet to fully erode. In between the mountain ranges, Isla Sorna has flatter regions which contain grasslands, wetlands, and forests, while the mountains themselves are mostly covered in cloud forest environments similar to Isla Nublar. The highest mountains on Isla Sorna are in its center, where its largest volcanic peak once stood; it has collapsed on its southern side, leaving the caldera open in that direction. The largest river on the island, a tidal river sometimes referred to as the Deep Channel (Spanish: Canal Ondo), partially flows out of this collapsed volcanic peak as rainfall on the mountain runs off of it. Combining with other rivers from the island’s western and southern regions, this is the main source of fresh water to Isla Sorna (though salt water moves inland during high tide). Other, smaller bodies of fresh water fed by rain are found across the island; where these become stagnant, they turn into wetlands.

Isla Sorna has a cooler climate than islands closer to the mainland such as Isla Nublar despite being farther south, with temperatures at night becoming cool enough to cause breath vapor condensation (the relative humidity of the island’s air means that this can occur at somewhat warmer temperatures). Despite this, the island still falls within the tropical monsoon climate type according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system, with mean temperatures above 64° Fahrenheit (18° Celsius) and distinct wet and dry seasons. In Costa Rica, the rainy season lasts from May to mid-November, while the dry season lasts from mid-November through April. During the rainy season, Isla Sorna is known to experience severe thunderstorms and hurricanes, while otherwise its climate is typically warm and sunny. The northeastern region is the coolest and driest part of Isla Sorna (though it is still quite wet), whereas the region west of the Deep Channel is the warmest and wettest part.

The coast of the island consists of both rocky and sandy beaches, as well as numerous steep cliffs and rugged mountains. The cause for this variability is erosion; powerful waves batter some of the island’s coasts, wearing away weaker rock and leaving fine sands behind. Most of Isla Sorna’s sand beaches are typical yellow or orange sand. Along with forming sand beaches, wave action has resulted in the formation of numerous bays and lagoons around Isla Sorna, framed by peninsulas. The most prominent peninsula of the island is the northeastern one, sometimes called Trinity Point (Spanish: Punto Trinidad), which is bordered to the west by the island’s largest bay, which is sometimes called the Arm of the Sea (Spanish: Braso de Mar). Trinity Point and its associated mountain peak High Point (Spanish: Punto Alto) are separated from the rest of the island by a deep gorge. South of this is a mountain range, which on some maps is referred to as the San Fernando Mountains (Spanish: Sierra San Fernando), as well as some large areas of grassy plains and low-lying woodland. These extend toward the island’s center, which is dominated by the collapsed volcanic caldera. Underneath, the island is probably riddled with lava tubes and caves as a result of prehistoric and recent volcanic activity.

The island’s western region consists of grasslands, low hills, and marshy rainforests surrounded by the second-highest mountains on the island. Parts of the Deep Channel extend well into this region, fed by rainwater and sheltered in the north by towering cliffs. Some regions of rainforest in the south were deteriorated during the 1990s and early 2000s by an overpopulation of de-extinct animals; since their removal, the jungle may have recovered. However, as the island is still off-limits to civilians, its current status cannot be determined.

Isla Sorna’s environment varies between the regions of the island. Its dramatic mountain ranges partition the island, allowing unique and variable climates to develop in the valleys between. Most of these consist either of open grassland (encouraged by the de-extinct wildlife once bred on the island) or tropical rainforest. Some of the central and eastern parts of the island consist more of temperate rainforest and hardwood forests. The most unique are the redwood forests found in the island’s northeast and to a lesser degree in the interior; they contain the only wild-growing coast redwood trees found outside of the West Coast of North America. Isla Sorna’s particular geography creates exactly the kind of environment that these trees need to thrive, perfectly mimicking the coastal American highlands that they otherwise inhabit. This geographic disparity is currently unexplained, but human intervention has been suggested.

Off of Isla Sorna’s coast are small rocky islets and reefs, with the two known named islets being the Great Rock (Spanish: La Roca Grande) to the northwest and the Dead Rock (Spanish: La Roca Muerta) to the southeast. A third islet lies to the south; its name is currently unknown. To its northeast of the island, according to older maps, is a submarine valley called Deep Point (Spanish: Punto Ondo). Unlike the main island, the islets are not heavily forested and mostly consist of rocky points and smaller plant life. They, and Deep Point, provide habitat to various marine animals in the surrounding waters.

History

Origin

Isla Sorna was the third member of the Muertes Archipelago to form, created from the same volcanic hotspot that resulted in Isla Matanceros and Isla Muerta before it. While the exact period of time it formed is unknown, it is believed that the islands of the Gulf of Fernandez are all about as old as Cocos Island, between 1.91 and 2.24 million years old; Isla Sorna would have formed toward the later half of this time range. Its creation can mostly be attributed to a large volcano in its central region, which still shows some signs of minor geothermal activity and therefore may be classified as dormant. Other volcanoes may have existed in the northeastern and western regions due to higher mountains in these areas, but any volcanoes there are believed to be extinct.

The first creatures to inhabit Isla Sorna were most likely marine animals, such as birds, seals, and sea lions, which used the island as a place to rest or breed. Because two other islands existed before it, however, Isla Sorna would quickly have become home first to plant life and then to terrestrial animals which dispersed from the nearby Isla Muerta. Because of the archipelago’s isolation, it is likely that many organisms that evolved here are endemic, but it is also home to animals and plants found in Central America and on other Pacific islands.

Over time, dense forests established themselves on Isla Sorna, fed by rainwater which created rivers and lakes on the island. The central volcano eventually became dormant; weathering and erosion broke down its southern face, creating a funnel-like structure which collected rainwater and concentrated it in a southward-flowing tidal river. This became the Deep Channel which today is still the most prominent river on Isla Sorna. Wave action on the coasts broke down some (but not all) of the cliffs, creating many sandy beaches and large bays around the island’s border. These natural events gradually shaped Isla Sorna into the island it is today.

1526-1982: Human inhabitants

In the novel canon (C/N), the Muertes Archipelago was once inhabited by native peoples who likely emigrated from Central America, but this is not stated in the film canon. The archipelago in the film canon is located considerably farther from the mainland as well, making it less feasible for people to reach the island in ancient history. However, the 120-mile journey to Isla Nublar from Costa Rica was made thousands of years ago by the Bribri people, making it possible that a further 87 miles could be traversed by skilled seafarers in the region. Some minor canons, such as the Jurassic Park: Dinosaur Battles video game, also suggest that Isla Sorna was once inhabited by humans in prehistory (this game’s canon even implies that the island’s inhabitants may not have been Homo sapiens sapiens but a close relative).

In the true film canon, the first confirmed human discovery of Isla Sorna is believed to have been in 1526, one year after European discovery of Isla Nublar. The names of the archipelago’s islands heavily imply that the Spanish were the first Europeans to locate them, leading some to suggest that they were also discovered by La Estrella under Diego Fernandez. There is dispute among historians about the Muertes Archipelago’s discovery, however; the date of 1526 is not universally accepted, casting doubt on many aspects of the archipelago’s discovery including the origin of its name and who among Europeans originally located it.

Throughout history, Isla Sorna was used for its resources. Humans introduced banana plants to the island at some point in the past, growing the fruits in the island’s warm, tropical climate on several locations across Isla Sorna. This use continued into relatively recent times. Humans also introduced some invasive plant and animal species to Isla Sorna, including elephant grass and rats. Apart from this, the island appears to have been of low cultural significance, overshadowed by more impressive and historically important islands in the region such as the Galápagos. The country of Costa Rica became recognized in its modern form on November 7, 1949; sometime after this, it assumed control over islands in the Gulf of Fernandez, including the Muertes Archipelago.

1982-1995: InGen ownership

In 1982, International Genetic Technologies, Inc. leased Isla Sorna and the surrounding islands from the Costa Rican government for the purpose of genetic research at the behest of CEO John Hammond. The lease was to last 99 years, allowing InGen all the time it needed to perform its research. When the lease was finalized, the banana plantation workers were relocated off Isla Sorna; the plantations themselves were left abandoned and mostly untouched as they would provide food sources to local animal life such as monkeys and sloths. During the early 1980s, InGen established facilities for its employees there, including the Workers’ Village (Spanish: Campo de Trabajadores) in the central part of the island. Geothermal power was used as a source of electricity, which likely was why the village was constructed in the central island where the remains of the old volcano are located. The facility on Isla Sorna became known as “Site B,” as opposed to the planned de-extinction theme park Jurassic Park, which would have been Site A. Hammond’s business partner Robert Muldoon, who was intended to be Jurassic Park’s warden, was involved with Site B from its inception and likely oversaw much of the construction.

Research was also ongoing at various offsite locations, including the Lockwood estate in northern California. In 1984, Hammond and his business partner Benjamin Lockwood succeeded in test-fertilizing an artificial ovum; a year later, newly-hired paleogeneticist Dr. Laura Sorkin proved that prehistoric DNA could be recovered from the blood meals of hematophagous organisms preserved in amber. This was the first step toward de-extinction, which was researched on Site B. As research on the island began, Lockwood’s young daughter Charlotte began spending time on Isla Sorna in the laboratories, and by the age of fourteen she was living there full-time. Charlotte was tutored by InGen’s scientists.

By 1986, InGen had constructed a de-extinction research facility on the island. Geneticist Dr. Henry Wu was hired that same year, and InGen succeeded in cloning a healthy, living Triceratops horridus using methods pioneered by Drs. Sorkin and Wu. Other dinosaur genera, such as Microceratus and Brachiosaurus, were also created in the early years of de-extinction; the first known theropod, Tyrannosaurus rex, was first cloned in 1988. Wu’s successes were due to his innovative but controversial methods of hybridization; InGen found that ancient DNA was typically recovered in a seriously decayed state. While Dr. Sorkin had completed these damaged genomes by cross-referencing dozens of amber samples looking for compatible genes belonging to the same species, Dr. Wu completed repairs in a much shorter time by filling in the decayed segments using homologous or analogous DNA from extant amphibians, reptiles, and birds. His methods were greatly supported by Hammond and approved of by most of InGen because they got results, but Dr. Sorkin opposed Wu’s methods due to the phenotypic anomalies they sometimes caused in the modified animals. Another point of contention was the lysine contingency, intended to kill escaped animals; InGen approved of this safety measure, though Dr. Sorkin strongly opposed it. Accepting the lysine contingency as official InGen policy became a required part of new employment applications.

Dr. Wu was chosen by InGen to lead the genetics department due to his accomplishments, and Dr. Sorkin was eventually moved to perform population research from Isla Nublar (which by 1985 had been selected as Site A) so that Wu could continue work on Site B unhindered. The existence of Site B may have only been known to certain InGen employees, as the InGen IntraNet website contains an archived email from John Hammond indicating that its computer network was kept under extreme security measures. Such safety practices were not without reason; corporate rivals such as BioSyn were aware that InGen was conducting valuable research and made attempts to illegally obtain the results.

In 1988, some dinosaurs were approved for relocation to Site A for Jurassic Park. These included some of InGen’s earliest successes, such as Triceratops, Microceratus, and Brachiosaurus; a year later, the oldest surviving Tyrannosaurus was also relocated off the island. Not all of the animals were destined for the Park. Many were left on Site B for research purposes, maintained in small paddocks located across the island.

By the end of the 1980s and into the early 1990s, InGen succeeded in bringing back from extinction a number of animals and plants. Not all the results were as expected; a genus called Dilophosaurus was found to contain highly-developed venom glands, which may have been the result of Wu’s hybridization. Another theropod genus, Velociraptor, was more troublesome: embryos had failed due to karyolysis, which Dr. Wu found on September 20, 1991 was a result of incompatability with gene donors that had worked in other theropods such as Dilophosaurus. Upon changing the gene donor to the common reed frog (Hyperolius viridiflavus), Wu succeeded in cloning the dinosaur, but with more phenotypic anomalies than perhaps any other resurrected species. By February 13, 1992, Wu and Muldoon had determined that Velociraptor exhibited surprising levels of collective intelligence; despite this making the animal a security risk, it was destined for Jurassic Park.

Construction continued on Site B well into the 1990s, as did de-extinction. An aviary was created at some point to house Pteranodon, InGen’s first flying reptile success. Other de-extinct species created on Site B by 1993 included Parasaurolophus, Carnotaurus, Stegosaurus, Baryonyx, Mamenchisaurus, Pachycephalosaurus, Compsognathus, Edmontosaurus, Apatosaurus, Herrerasaurus, Geosternbergia, and Gallimimus. Additionally, Tylosaurus and Troodon may have been bred here initially (though these genera were exclusive to Isla Nublar by 1993); it has been suggested that Iguanodon and Diplodocus were as well, but this is unlikely. The populations of some of these animals were depleted throughout the 1980s and 1990s as many individuals were shipped to Site A for exhibition, apparently including all of the Herrerasaurus as none remained on Isla Sorna by 1993. In addition, it appears that the Apatosaurus population died out before 1993 for unknown reasons, as they were not included in an InGen asset summary from 1993.

Operations on Isla Sorna were still underway in early June of 1993, when a Velociraptor on Isla Nublar mauled a worker to death. This stunted development of Jurassic Park, as InGen’s Board of Directors insisted that the Park be reviewed for safety by a team of outside experts before major development continued. This delay did not affect Isla Sorna immediately, and construction on new projects such as a marina in the Deep Channel and the first of several safe houses. By this time, Lockwood was no longer involved with InGen; Hammond, Muldoon, and Wu were only infrequently on Isla Sorna at this point as Jurassic Park’s construction had taken precedence. The inspection tour commenced on June 11 after some preparation, and ended disastrously with the deaths of multiple InGen employees including Muldoon.

Research and development on Isla Sorna slowed as InGen suffered a major financial blow. Hammond decreased activity on the island as the incident caused a major philosophical change in him; he rejected capitalism in favor of a naturalist approach, working to protect the animals his company had created. This was the beginning of the end for Hammond’s time at InGen, as he rejected proposals to contain the animals of Isla Sorna for a reopened Park. Evidence was uncovered in 1994 that the animals had survived the lysine contingency, but it was unknown why. Animal populations on Isla Sorna became harder to track due to their unexpectedly high survival rate, unauthorized breeding, and reduced staff.

In 1995, financial troubles and the approach of Hurricane Clarissa forced InGen to move its operations off of Isla Sorna. During the evacuation, animal paddocks were left unattended and with security measures left off, allowing the animals to move fully into the wild where they would presumably die of lysine deficiency within a week or so. InGen had not taken into account that the dinosaurs, like all animals, could easily obtain lysine from environmental sources such as beans, eggs, and fish. Hurricane Clarissa caused serious structural damage to Site B, rendering much of its facilities inoperable. Dinosaurs were not the only assets left behind; many vehicles and supplies were also abandoned, suggesting that InGen’s evacuation was hasty and inefficient rather than organized and moderated.

The animals, once released into the wild, found environmental sources of lysine and began to thrive and breed. Their populations began to rise, and territories were established.

An age of dinosaurs: 1995-1998

De-extinct animals roamed freely over all of Isla Sorna after Hurricane Clarissa, establishing territories and a unique ecology on the island. At least one subspecies of Pteranodon was able to get into the wild after 1995, but did not leave Isla Sorna as the island appears to have provided all the environmental requirements they needed.

Many of the animal populations flourished in the absence of humans, breeding prodigiously and thriving in the wild. Others, such as Edmontosaurus, appear to have suffered due to low population starting levels and heavy predation from the carnivores on the island. Tyrannosaurus quickly established as Isla Sorna’s apex predator, with no similarly-large carnivores to challenge it. This animal could easily prey on most of the island’s animals, with the exception of healthy adult sauropods, and regulated the populations of smaller creatures. Most of the larger carnivores migrated to the island interior, while many herbivores kept to the coastal forests. InGen continued to monitor the island after discovering that the lysine contingency had failed.

Human interference on the island was minimized for several reasons. First, the island’s isolation meant it was unlikely to be visited by outsiders, and the locals had all been relocated at InGen’s orders. Some local fishermen are believed to have perished on the island, which compounded with superstition surrounding the Muertes Archipelago kept people away. InGen itself sought to continue the Jurassic Park project despite the failure of Isla Nublar, but the Park’s failure eventually brought John Hammond to abandon capitalism as a philosophy and become highly environmentalist instead. Due to this philosophical change, Hammond blocked InGen from using Isla Sorna for any purpose and left it in an abandoned, wild state. This led to many higher-ups in InGen, including Hammond’s own nephew Peter Ludlow, to lose faith in Hammond and seek to remove him from his position.

They would get their opportunity in December of 1996, when the Bowman family stopped on Isla Sorna while on a yacht cruise through the Gulf of Fernandez. Their daughter was attacked and wounded by a pack of Compsognathus on the northwestern beach after she fed them, and she was brought to the mainland for emergency medical attention. Upon learning that InGen had leased Isla Sorna, the Bowmans threatened to sue the company. Ludlow took this opportunity to move the Board to depose Hammond, and over the course of 1997, he made preparations to move dinosaurs from Isla Sorna to the almost-finished Jurassic Park: San Diego. Hammond made plans of his own to reveal the island’s animals to the public in the form of a nature documentary and generate public support for the preservation of Isla Sorna, hiring paleobiologist Dr. Sarah Harding to perform initial research while a documentary team would arrive later. This team would include video documentarian Nick Van Owen, equipment specialist Eddie Carr, and Jurassic Park survivor Dr. Ian Malcolm. Without permission, Malcolm’s daughter Kelly Curtis also accompanied the mission. Ludlow’s team included multiple InGen Security personnel, big-game hunter Roland Tembo, vertebrate paleontologist Dr. Robert Burke, equipment specialist Dieter Stark, and Tembo’s associate Ajay Sidhu.

Ludlow’s mission, called the Harvester operation, landed on Isla Sorna in 1997 shortly after Hammond’s Gatherer operation (sans Dr. Harding, who had arrived some time prior). Both teams landed on the northeastern peninsula, the Gatherers arriving via the Mar del Plata and taking field equipment and vehicles from a small lagoon to the northeastern cliffs and the Harvesters arriving via the S.S. Venture and taking helicopters to the game trail in the same area. The Harvesters set up an encampment in the nearby forest, capturing multiple dinosaur species intended for Jurassic Park: San Diego. In addition, the Harvesters’ lead hunter Tembo captured a juvenile tyrannosaur with the intent to lure the animal’s father out for a trophy killing.

Hammond’s Gatherers, particularly Van Owen, sabotaged the Harvesters by cutting the fuel lines to their vehicles and releasing the dinosaurs while the Harvesters were busy with a Board teleconference. An angry male Triceratops demolished the camp and the dinosaurs fled into the forest; Tembo and his partner Sidhu were distracted by the attack and Van Owen was able to obtain the juvenile tyrannosaur. It was brought back to the Gatherers’ camp to treat injuries Ludlow had accidentally given it; while Harding and Van Owen were able to treat the animal’s broken leg, its distress cries attracted its father and mother, who proceeded to destroy the Gatherers’ camp after their infant was returned to them. This left both the Harvesters and Gatherers without a means by which to contact their respective transport off the island.

Over the course of the next day, both groups made their way inland toward the Workers’ Village to use the geothermally-powered Operations Center to reach the S.S. Venture and InGen’s Harvest Base. They were stalked by the tyrannosaur parents along the way, including a chaotic attack during the night which drove the survivors into Velociraptor hunting grounds. Van Owen was able to reach the Harvest Base and send for rescue; meanwhile, Tembo was able to heavily tranquilize the male tyrannosaur after finding his bullets stolen by Van Owen. Ludlow wasted no time in airlifting the tyrannosaur to the S.S. Venture and recapturing the infant, leaving the female alone on the island as the survivors left. The missions resulted in numerous deaths, including Carr, Stark, Burke, and Sidhu.

The following day saw the return of the father and son tyrannosaurs to Isla Sorna at approximately 11:30am, and they reunited with the mother. Isla Sorna remained at peace for a time, but thousands of miles away, its fate was heavily debated by the public and government. It was no longer a hidden environment, as the tyrannosaurs had appeared blatantly before hundreds of people and were featured in news stories around the world. Hammond worked with the U.S. and Costa Rican governments to create the Gene Guard Act, which established legal protections for de-extinct animals and outlawed further genetic research; even then, Hammond was dying, and passed away at the end of 1997. The following year, the struggling InGen was bought by Masrani Global Corporation. Its CEO, Simon Masrani, was the son of John Hammond’s friend Sanjay Masrani, and had ambitions to reopen Jurassic Park at the Isla Nublar location. This effort would begin a new age for Isla Sorna, and one of uncertain future.

1998-2005: Ecological crisis

In 1998, InGen was bought by Masrani Global Corporation and became a subsidiary. Within one hundred days of this buyout, activity resumed on Isla Sorna in direct violation of the Gene Guard Act passed the previous year, despite United Nations and other governmental entities keeping surveillance over the island. It is unknown whether or not Simon Masrani himself was aware of this crime, but there is reason to believe Henry Wu was involved directly. During a nine-month period in 1998 and 1999, the Site B facilities were reused to continue de-extinction research and development for the second incarnation of Jurassic Park on Isla Nublar. At least four new genera are known to have come of this: at least one each of Ceratosaurus and Spinosaurus, which were new species to InGen, several Ankylosaurus, and a huge number of Corythosaurus. These latter two were based on reconstructed genomes that InGen had already partially or mostly completed. While unconfirmed, Iguanodon and Diplodocus may have been cloned during this period of time. This research furthered Dr. Wu’s studies into hybridization between genera, which he had discovered was possible due to his work in the 1990s. InGen’s rival Biosyn Genetics infiltrated the illegal research in 1999 through its Project Regenesis, succeeding at piggybacking off of Dr. Wu’s success to bolster Biosyn over the next two decades.

In 1999, Isla Sorna was abandoned again as InGen feared the government would discover its illegal activities. The animals, which had been bred and subject to accelerated growth, were turned out into the wild to join the creatures already living there. The addition of so many new animals unbalanced the already crowded environment, with the scores of new herbivores overgrazing parts of the island and the gigantic Spinosaurus becoming a competitive apex predator. Masrani Global was granted limited access to the island in 1999, and Simon Masrani visited Isla Sorna himself; this was the beginning of the end of the Gene Guard Act, which would be essentially nullified in 2003. Biosyn left Isla Sorna in 2000 as InGen gained more access to the island. InGen’s illegal activity on Site B was almost exposed in 2001 due to an eight-week incident involving several Americans becoming marooned on the island, forcing certain Masrani Global higher-ups bribing government officials into censoring parts of the incident and burying the survivors’ testimonies. The incident also caused the death of one of the island’s tyrannosaurs, further unbalancing the fragile insular ecology.

The overpopulation of Isla Sorna was not the only threat to its ecosystem. Now that the island was publicly known, despite the UN and other entities watching over Isla Sorna, it was the target of exotic animal poaching. The de-extinct species there were the rarest animals in the world, and would fetch a high price on the black market. Captured specimens were often mishandled, leading to violent conflict between humans and de-extinct animals. It is unknown how many animals and of which species were removed from Isla Sorna by exotic animal poachers, but at least some are believed to have reached the Costa Rican mainland. Gruesome injuries have been reported and attributed to mishandled dinosaurs.

According to the Jurassic Park Adventures junior novel series, Isla Sorna was monitored from 2001 onward by a UN bureau created to keep the peace on the island, keep poachers away, and study its de-extinct wildlife for the benefit of both humanity and the creatures themselves. While this is not certain in the film canon, it would have ended in 2004 or 2005 anyway due to the ongoing overpopulation problem (which is discussed in the JPA books, though these only cover events leading up into 2002). Masrani Global Corporation had, in April 2002, succeeded in recapturing Isla Nublar as planned. Some of the dinosaurs, including all the surviving Brachiosaurus and Triceratops, were relocated back to Isla Sorna, further exacerbating the overpopulation issue. They were maintained here until 2004, when the crisis reached a turning point. At this time, it was finally noticed by scientists studying the island; animal populations plummeted, threatening many of them with extinction. While certain InGen and Masrani Global officials almost certainly knew the cause of the crisis, most scientists were puzzled, blaming factors such as disease and territorial behavior. Simon Masrani appears to have believed that poaching was the primary cause for the population collapse, implying that if he did know about InGen’s operation during the late 1990s, he was not aware of the scope of its effects.

Masrani Global took action to save the animals, rounding them up and transporting them to Isla Nublar. This began in January 2004 with the return of two female Brachiosaurus that had originally come from Isla Nublar; in the spring, a Triceratops herd was moved, as were two Sorna-hatched juvenile female Brachiosaurus. By the summer, Parasaurolophus and Gallimimus had been taken from Isla Sorna, as had the eggs of numerous species including Ankylosaurus. The first carnivore known to be relocated was a female Velociraptor, moved in September of 2004; the raptors were moved one at a time, intended to prevent them from organizing against their captors during transport. By the time Masrani Global’s new park, Jurassic World, opened on May 30, 2005, Isla Sorna was officially said to be entirely devoid of dinosaurs, leaving the whole de-extinct animal population on Isla Nublar.

2005-present: Status unknown

According to official Masrani sources, Isla Sorna is currently abandoned and does not house any de-extinct life. Even Masrani Global higher-ups such as Claire Dearing appeared to entirely believe this and did not appear to have made any investigation into Site B’s status. Nonetheless, Isla Sorna remained a restricted area even as it was allegedly emptied. A joint taskforce of the United Nations and InGen Security patrolled the island for over a decade, attempting to prevent poachers from landing on the island.

A record number of poacher vessels were apprehended in the Gulf of Fernandez in 2013, including many near the Muertes Archipelago, almost a full decade after Isla Sorna was supposedly emptied. It has been suggested that they were following rumors, and that the island truly is empty, but the sheer number of vessels sighted near the archipelago is still a source of suspicion. It was discovered in 2016, mere months after Jurassic World closed, that InGen had been operating offsite locations including at least one in the Atacama Desert of Chile; this means that there is precedent for the idea that Isla Nublar was not, in fact, the home of the world’s last de-extinct animals as Jurassic World claimed. InGen was not the only company to do this; its longtime rival Mantah Corp illegally appropriated assets between 2001 and 2015, holding them at an island facility east of Isla Nublar. This included some Isla Sorna specimens, including a Spinosaurus and two Tyrannosaurus, as well as a Brachiosaurus DNA sample. Then, there is the fact that Masrani Global did not relinquish ownership of Isla Sorna and did not permit the Dinosaur Protection Group to relocate the threatened animals of Isla Nublar to that location in 2018; if operations were truly continuing on Isla Sorna as is suspected by some, it would be in their best interest to keep whistleblowers such as Claire Dearing away.

Leaked emails from within Biosyn Genetics further confirm that some animals did in fact survive the collapse. In 2017, a disguised vessel operated by Biosyn was apprehended by the U.S. Coast Guard. Biosyn’s CEO Lewis Dodgson orchestrated bribery to placate and silence the captain and crew of the Coast Guard vessel involved; a cover story involving an imperiled tourist boat was fabricated to explain the incident. It is strongly believed that the Biosyn vessel was part of a larger-scale operation to remove animals from Isla Sorna, bringing them to Biosyn Valley. Two of the animals aboard the vessel were the mated pair of tyrannosaurs involved with the 1997 incidents; their offspring was not confirmed on board.

Currently, Isla Sorna is monitored mostly by the Costa Rican government along with a number of third-party companies formerly including Biosyn (as of 2022 it is no longer involved). The island’s status, including how many animals and of which species still live there, remains mysterious. Descriptions by the intergovernmental Department of Prehistoric Wildlife are currently the public’s only real look into what is happening on Isla Sorna now, and these are few; they confirm only that de-extinct animal life may be living there under DPW supervision. Although authorities have repeatedly insisted that the island no longer houses any de-extinct life, the facts at hand have consistently indicated otherwise, fueling long-held suspicions that something has survived.

Cultural Significance

Unlike Isla Nublar, there is no direct evidence that Isla Sorna (or any member of the Muertes Archipelago) was inhabited long-term by any Indigenous Americans. In fact, the first confirmed instance of people living on the island were banana plantation workers during historically recent times. These workers remained on Isla Sorna maintaining banana groves until 1982, when InGen’s leasing of the island forced them to relocate.

Isla Sorna’s history is still only partially known, due in no small part to InGen and Masrani Global remaining reluctant to release any information at all about what happened on the island. Most of what is known come from the 1997 and 2001 incidents, and these testimonies provide only fragmentary glimpses into what InGen really did on Isla Sorna. Secretive archived notes recovered from the Masrani Global Corporation website backdoor suggest that, during both periods of activity on the island, strange happenings surrounded the research that took place there. Much of these occurrences were related to Dr. Henry Wu’s groundbreaking, if controversial, genetic engineering projects; it was here that he discovered how to hybridize different genera to create life forms that had not existed before. His work on Isla Sorna during the 1980s and 1990s led to his creation of the hybrid species Karacosis wutansis in 1997, and his likely involvement in the illegal nine-month operation in the late 1990s formed precedent for his creation of the hybrid species Indominus rex in 2012. Isla Sorna provided him, and the rest of InGen, with a convenient laboratory and factory floor far away from prying eyes.

Until the revelation of Jurassic World in 2002, Isla Sorna was actually better-known to the public than the smaller, more obscure Isla Nublar. InGen had operated on Isla Sorna long before Isla Nublar was even considered for Jurassic Park’s location, and the original San Diego location was revived in 1997 by Peter Ludlow. This culminated in assets being seized from Isla Sorna, with a father and son Tyrannosaurus being brought to San Diego. The adult was accidentally released into the city streets, revealing de-extinction to the public in a dramatic but unplanned manner. Some members of the public confused Isla Sorna with Isla Nublar, assuming that only one island had been used by InGen for de-extinction research.

Illegal tourism flourished around Isla Sorna during the ensuing years, even as InGen briefly performed research on the island in violation of the Gene Guard Act. The UN monitored the island, with InGen Security eventually joining in; despite the security around Isla Sorna, illegal tourism resulted in an incident in 2001 in which two Americans were marooned on the island. A young Oklahoman boy, Eric Kirby, was the sole survivor of the initial incident; his adult companion died of injuries sustained during a paraglider crash, and their Costa Rican guides were killed by as-of-yet-unidentified animals. These were not the first incidences of local boaters dying on Isla Sorna; similar incidents had occurred as far back as the mid-1990s. This incident, however, gained the attention of the U.S. government as celebrity scientist Dr. Alan Grant eventually became involved with a kidnapping intended to gain his help in rescuing Eric.

While government officials were bribed by Masrani Global Corporation representatives to bury the testimonies of Eric Kirby and other survivors of the 2001 incident, some of the corporation’s representatives would undo this protection in 2015 and 2016. Government inquiry into bioethical misconduct by Henry Wu was supplemented by documentation provided by Masrani Global employees and at least one anonymous hacker, much of it concerning Isla Sorna and the illegal activities that took place there in the 1990s. Before the closure of Jurassic World, though, Masrani Global was well aware of and willing to capitalize on the mystery surrounding Site B; when a lottery was held to win a trip to Camp Cretaceous in 2015, the method was to win a virtual reality video game which took place on Isla Sorna.

Since 2004, Isla Sorna and its difficult history have been commonly seen as symbols of avarice, greed, and hubris. Even in 2004, when the truth behind the ecological catastrophe was not yet public knowledge, Simon Masrani firmly believed that poaching was to blame rather than disease, territoriality, or other natural causes. Site B was viewed as a failure, doomed to its fate by exploitation; Simon Masrani himself would exploit the crisis on Site B to harvest its animal assets for Jurassic World. The revelation in 2016 that Masrani Global Corporation had been directly responsible for the island’s overpopulation (publicized by the Dinosaur Protection Group in 2018) changed Isla Sorna’s cultural symbolism from that of simple greed to that of large-scale corruption. The island was said for many years to be abandoned, but there has always been doubt surrounding this claim, and as time goes on it becomes more evident that Isla Sorna was never fully emptied of its prehistoric inhabitants. Today, access is tightly controlled, and it is unknown what is really going on there.

Ecological Significance

For millions of years, Isla Sorna was home to countless plant and animal species. These lived relatively untouched into the modern day, spared from human interference by the island’s isolated locale over 200 miles from the nearest coastline. Some mammalian life is found on the island, including Hoffmann’s two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni) as well as some species of opossums, monkeys, and bats. There are also amphibians, such as the strawberry poison-dart frog (Oophaga pumilio), which breeds in the central caldera. Reptiles include lizards such as iguanas, as well as a great many snakes; as many as seventeen venomous snake species as well as non-venomous snakes such as the milk snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) inhabit the island. Some of the snakes can grow rather large. A great many bird species also inhabit Isla Sorna. Invertebrate life abounds here, including many species of butterflies and moths, spiders including tarantulas, scorpions, ticks, mosquitoes and other biting insects, and flies. The presence of poison-dart frogs implies the presence of rover ants, which the frogs eat to become poisonous to their predators. In the surrounding ocean, there are abundant fish such as striped bonitos, which may venture into the Deep Channel to feed on smaller crustaceans.

Plant life on Isla Sorna is more variable than some of the other islands in the Gulf of Fernandez owing to the island’s unique geography. A cooler, misty environment in the northwest supports an ecosystem reminiscent of the American West Coast, including the only coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) outside of that region. The western region of the island is warmer and wetter, supporting a more traditional tropical rainforest. Plants such as ivy, giant chain ferns, and rubber plants thrive on Isla Sorna, as well as the garlic tree (Caryocar costaricense), a rare endangered species. Agama beans appear to be endemic to Isla Sorna, as they are not known from anywhere else.

In recent times, invasive plants such as elephant grass have been introduced to the island and become common. Invasive species on the island also include animals such as brown rats and intentionally-introduced crop plants including soybeans and the banana. While bananas were originally introduced to grow in the form of plantations, they have continued to survive after being abandoned in 1982 due to the fact that indigenous mammals feed on them and disperse the seeds.

Since 1986, Isla Sorna has also known invasive de-extinct species, including some large animals that have powerfully altered the local environment. These include huge herbivorous dinosaurs, the largest of which (sauropods such as Brachiosaurus and Mamenchisaurus) can drastically reduce forests in their area. The more moderately-sized herbivores were kept in check by carnivorous dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor, but these introduced predators can also harm indigenous wildlife. Even the smallest carnivore on the island, Compsognathus, boldly ventures onto beaches where seabirds commonly nest and could pose a threat to native animals. Most de-extinct animals are considerably larger than any native animal species from Isla Sorna, with only some of the largest native birds and reptiles outsizing the smaller dinosaurs. Even so, dinosaurs were not completely safe from native life on Isla Sorna; in Eric Kirby’s book Survivor, he documents a large snake (possibly a bushmaster or a boa) attempting to feed on a baby Ankylosaurus.

De-extinct life on Isla Sorna was present between 1986 and 2005, with all cloning activity occurring in two distinct phases between 1986-1993 and 1998-1999. Some activity may still be occurring. The following is a list of de-extinct animal species known to have existed on Isla Sorna, as well as dates at which they are believed to have first been created:

- Triceratops horridus – 1986

- Brachiosaurus “brancai“ – 1986?

- Parasaurolophus walkeri – 1980s?

- Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis – 1980s?

- Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum – 1980s?

- Stegosaurus stenops – 1980s?

- Microceratus gobiensis – 1980s?

- Apatosaurus sp. – 1980s? (extinct by 1993)

- Hadrosaurus foulkii – 1980s? (extinct by 1993)

- Maiasaura peeblesorum – 1980s? (extinct by 1993)

- Baryonyx walkeri – 1980s?

- Carnotaurus sastrei – 1980s?

- Tyrannosaurus rex – 1988

- Edmontosaurus annectens – 1990s?

- Pteranodon longiceps – 1990s?

- Geosternbergia sternbergi – 1990s? (classified at the time as Pteranodon)

- Compsognathus “triassicus“ – 1990s?

- Tylosaurus proriger – 1990s? (may never have been bred on Isla Sorna)

- Troodon pectinodon – 1990s? (may never have been bred on Isla Sorna)

- Dilophosaurus “venenifer“ – 1991-1993

- Velociraptor “antirrhopus“ – 1991-1992

- Gallimimus bullatus – 1991-1992?

- Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis – 1992-1993 (all removed in 1993)

- Corythosaurus casuarius – 1998-1999 (possible brief existence before 1993)

- Ankylosaurus magniventris – 1998-1999

- Spinosaurus aegyptiacus – 1998-1999

- Ceratosaurus nasicornis – 1998-1999

- Iguanodon bernissartiensis – 1998-1999? (existence is debated)

- Diplodocus carnegii – 1998-1999? (existence is debated)

Additionally, there are several species which existed only as genome samples at the time.

The facilities constructed to breed and house dinosaurs have also impacted the island’s natural ecology, clearing large areas of forest to build laboratories and employee housing. Shipping and air traffic around the island increased because of InGen, and not only as a direct result of their own activities. Poaching vessels are now common around the Muertes Archipelago, and the illegal activities of poachers almost certainly disrupt native life on the islands.

After being influenced by nonnative de-extinct life for eleven years, Isla Sorna was supposedly restored to its natural state and abandoned by May 2005. If this were true, it would mean the island’s native wildlife and ecology were no longer threatened by human presence or de-extinct life. However, reality is more complicated. Evidence has mounted for many years that Isla Sorna was never fully depopulated, and that InGen and other parties remain active there. Operations on the island seem to be ongoing even now, hidden from those who do not have a need to know.

Behind the Scenes

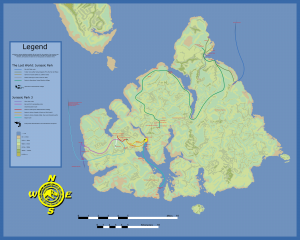

Isla Sorna Maps

This map is from the original prop believed to be produced shortly before the ending was changed for the ending San Diego sequence. The final Isla Sorna we see undergoes another topography as well as scaling change after the map we see here. To make the matter more confusing is that this map was seen at the travelling exhibit, “The Dinosaurs of The Lost World & Jurassic Park” and runs in conflict to the island’s topographical features of the final product seen by Kelly Curtis within the Mobile RV Lab’s Primary Trailer. Also note the Embryonics Administration is in fact, not named, but the worker town is. Again this map was produced before the ending of San Diego sequence was fully realized and way before the concept of the third sequel was even created.

This map is from the original prop believed to be produced shortly before the ending was changed for the ending San Diego sequence. The final Isla Sorna we see undergoes another topography as well as scaling change after the map we see here. To make the matter more confusing is that this map was seen at the travelling exhibit, “The Dinosaurs of The Lost World & Jurassic Park” and runs in conflict to the island’s topographical features of the final product seen by Kelly Curtis within the Mobile RV Lab’s Primary Trailer. Also note the Embryonics Administration is in fact, not named, but the worker town is. Again this map was produced before the ending of San Diego sequence was fully realized and way before the concept of the third sequel was even created.

While this map presently isn’t 100% accurate it does serve the purpose of possible placement of events by lining up the topography and geographical features of the island, but the problem is no Isla Sorna map will ever be genuinely correct ever unless it takes into account both events of the second and third movies and comes from Universal itself. The movie moments placed on this map are highly speculative due to the nature of such a project undertaken to do a fan made “correct” map. The new map, to the left, is modified from the map Kelly views in the trailers, the thermal signatures map of Hammond’s, and the best detective work possible.

While this map presently isn’t 100% accurate it does serve the purpose of possible placement of events by lining up the topography and geographical features of the island, but the problem is no Isla Sorna map will ever be genuinely correct ever unless it takes into account both events of the second and third movies and comes from Universal itself. The movie moments placed on this map are highly speculative due to the nature of such a project undertaken to do a fan made “correct” map. The new map, to the left, is modified from the map Kelly views in the trailers, the thermal signatures map of Hammond’s, and the best detective work possible.

For a full on analysis please visit our Isla Sorna Map (S/F) – Notes and Annotations article.